不同於以往常見的國際性大展,印尼當代藝術團體 ruangrupa 在 2022 年所策畫的第十五屆卡塞爾文件展,不只透過大量東南亞的在地文化語彙,開展論述主軸的深度與廣度,同時也在各類型展演活動的組織方式與資源分配的策略上,以共享、共生的集體創作精神,形塑出此次文件展的獨特之處與時代意義。不過,當我們嘗試捕捉整體的展覽特質和其獨特性時,除了必須進一步耙梳跨地域間複雜的文化與歷史脈絡之外,在分析以「事件」和「參與」為主的展演模式的過程中,其實也很難避開書寫評論所可能面臨的困境。譬如,畢莎普(Claire Bishop)在《人造地獄》(Artificial Hells)開篇之處提及的,在不同時間和空間中持續開展的參與式藝術,無法只是藉由零碎的影像紀錄、圖片和物件所構成的視覺元素,來重現其團體動能、情感交流和社會情境變化的多重感知經驗。2 於是,研究者勢必得在資源與成本極其有限的情況下,仰賴特定的機緣和人脈關係,盡可能地解決現場經驗或第一手資料難以掌握的問題。又或者,在今日批判個人主義的言論、強調水平組織模式的趨勢和反對菁英品味的觀點愈加鮮明的氛圍內,二元對立的論述窠臼,也很可能不斷死灰復燃,而成為開展多元評論視野的桎梏。此外,另一個更值得深思的難題,則是在於如何從短暫、零星的訪談或參與經驗裡,以及從策展方法、創作行動和社會脈絡的交叉分析當中,擺脫類社會學研究和田野調查筆紀的箝制,並進一步提出適切的美學議題?

若以第十五屆文件展的重點項目「永續性計畫」(sustainability projects)為例,主辦單位撥取每張門票收入裡的一歐元,用以贊助德國黑森邦萊因哈特森林(Reinhardswald)的植樹方案還有印尼佩瑪當.卡包村(Pematang Kabau)的生態研究與藝術節,這樣的連結和合作模式,究竟是社會實踐還是藝術行動?3 多數較為關注展期內活動的觀者,似乎只能藉由開展前陸陸續續發布的新聞稿內容,來探知「永續性計畫」的一些蛛絲馬跡:2022年3月21日的國際森林日,ruangrupa 的禮薩.阿菲西納(Reza Afisina)和因達拉.阿曼(Indra Ameng),協同賴因哈茨哈根(Reinhardshagen)與包納塔爾(Baunatal)的植樹團隊,於萊因哈特森林的復育區,共同種下了橡樹幼苗。4 種植的過程中,禮薩和因達拉特地在一旁架設 DJ 播放音樂的平台,為現場增添了不少旋律和節奏,但也因此引發一些質疑藝術應否存在的歧見。5 另一方面,印尼佩瑪當.卡包村的「永續村落計畫」(The Sustainable Village Project),同樣並非僅限於 160 位學者為當地熱帶雨林之林相改造所進行的研究工作6,ruangrupa 透過文件展與這些生態學者共同建立起的合作關係,同時亦延伸到藝術團體 Rumah Budaya Sikukeluang 在3月中舉辦的跨領域藝術節(Semah Bumi Festival of Science, Nature, Society and the Arts)。然而,如果此類藝術活動或展演事件,不只是為了點綴社會實踐或喚醒民眾意識而存在,也不只是在體驗經濟下,作為提供愉悅感和文化產值的商品,那麼我們又該如何觀察藝術行動與社會實踐相互融合的潛能,並突顯「永續性計畫」內在的美學特質?

至少目前可以肯定的是,觀者其實難以經由報導內容和合作形式的描述,全然地感受到DJ音樂、森林、土壤、展演作品、節慶參與者、研究工作和植樹行為之間,既衝突又彼此交融的錯綜關係。而「永續性計畫」或文件展的美學特質,也因此很難被完整地彰顯。即便如此,我們不妨參照畢莎普在2004年評論關係美學(Esthétique relationnelle)時所提出來的分析方法。7 亦即,將「關係的質地」(quality of the relationships)作為探究第十五屆文件展的論述支點,以此去思考ruangrupa如何以集體式的創作行動,橫向地串接起與其他創作團體、觀眾、媒體、文化機關、政府單位等各類型參與者的關聯性,乃至於形構出和各種生態行動者之間的多重連結意涵。筆者認為,ruangrupa正是在這層與社會和生態的感性連結或關係當中,形塑出自身創作活動的美學特質。與此同時,我們在針對其關係質地與美學特質的研究裡,也能進一步觀察到此類型的藝術團體或「弱機構」(Institution faible)8,在生存與生態危機內所展現的藝術內在的政治能量,以及其不斷開創求同存異之共同體的力量。不過,在進入關係質地的分析之前,或許我們可以先從 ruangrupa 發展的歷史脈絡,探討他們跨國與在地的關係網絡如何產生?又具有哪些獨特的性質?

ruangrupa 的集體創作模式

這次文件展最引人注目的地方,莫過於圍繞在「穀倉成員」(lumbung members)和「穀倉藝術家」(lumbung artists)周圍所交織而成的關係網絡。這其中,包括了聯繫著展覽本身與展外活動的「跨域穀倉」(lumbung inter-lokal)、「印尼穀倉」(lumbung Indonesia)和「卡塞爾生態」(Kassel ekosistem),另外也觸及到藝術市場和獨立出版領域的穀倉參與者。9 尤其,ruangrupa 將發放資源的機構和代理者作為核心,以此開展如樹狀譜系般持續向外延伸、擴張的輻射網絡。這不僅翻摺出向來隱而不顯的機構關係與合作機制,也因而完整體現了當代藝術的全球化生產模式。

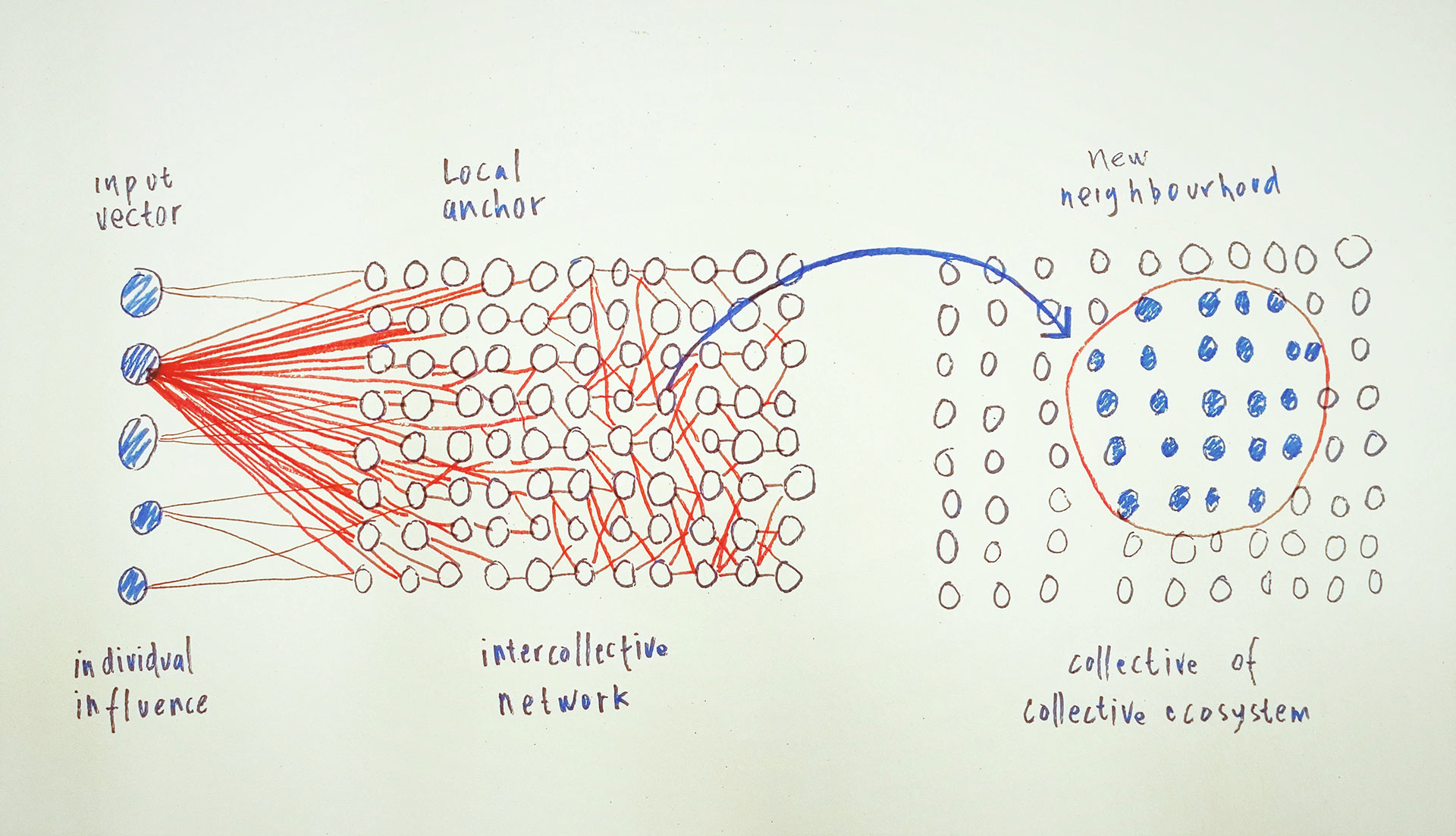

法國哲學學者寇克蘭(Anne Cauquelin)於1992年即著書認為,建立在「通信體制」(régime de la communication)之上的當代藝術,其生產模式已如實反映著「網絡」(réseau)信息傳播技術的運作型態。10 亦即,每一個當代藝術的參與者,就像是隨時可生成、切換屬性且同時具有輸出和輸入功能的「節點」(nœud);而這些節點在相互建立連結的過程中,便展現出網絡的延展性、多端點(multipolarité)和迴圈(circularité)的發展特質。11 換言之,節點或參與者的數量愈多,網絡的疏密層次就愈顯得複雜、多變。在此觀點下,寇克蘭亦進一步指出,當代藝術的生存條件和資本累積的關鍵,即是取決於節點間資訊傳播和流動頻率的高低,以及網絡連結量能與強度的多寡。12 若參照寇克蘭的論點,我們會發現,此一當代藝術的網絡組織模式,不只展現在文件展的穀倉網絡之中,其實早在 ruangrupa 成立之初,便有其脈絡可循。

印尼在蘇哈托獨裁政權瓦解後,旋即進入政治改革時期(Era Reformasi)。社會上滿溢著追求結社與言論自由、解放生活空間,以及積極關懷公共事務的群眾能量。在整體社會逐步轉型的背景下,剛從阿姆斯特丹皇家藝術學院(Rijksakademie)回到雅加達的艾德.達瑪萬(Ade Darmawan),和其他五位友人深刻感受到與群眾交流、對話的需求,於是以結交朋友、建立國際連結和組織網絡(networking)為核心目標,於2000年一起創立了 ruangrupa。13 同年,ruangrupa加入由阿姆斯特丹皇家藝術學院籌組的創作者網絡 RAIN(Rijksakademie Artist Initiative Network),以聯合拉美、亞洲和非洲的藝術團體,開展非西方主流的創作方法與在地文化知識的交流平台。14 此後,ruangrupa 開始陸陸續續藉由各大國際雙年展所匯集的「節點」,擴增與不同策展人和藝術機構之間的連結強度,並拓展自身創作活動的國際網絡。譬如,基於 2002 年光州雙年展和 2005 年伊斯坦堡雙年展的參展經驗,ruangrupa 在 2010 年十周年紀念展演活動的期間,已能展現出其建構國際連結的階段性成果。15 接著,在參加 2012 年亞太當代藝術三年展和 2014 年聖保羅雙年展之後,ruangrupa 則進一步轉為展覽策劃者的角色,於 2016 年荷蘭阿納姆的Sonsbeek 籌設第一次在歐洲的大型展覽。我們可以說,多年來,由於 ruangrupa 長期在國際上組織的關係網絡,使其得以在去年第十五屆文件展當中,透過各種不同的連結端點和管道,建立起更加龐雜且更具流動性的跨國合作平台。而在另一方面,ruangrupa 與其他印尼藝術團體共同串聯起的在地網絡,也同時對當地藝術生態和文化發展,產生重大深遠的影響。

關於在地網絡與生態發展的創作行動,較為顯著的例子,像是從 2003 年起,為了回應錄像工具普及化、網際網路的迅速崛起,乃至於日趨活躍的地下影視文化的現象,ruangrupa 籌辦了每兩年一屆的「OK. VIDEO」印尼國際媒體藝術節。這個國際藝術節,不僅提供來自世界各地的參與者一個創作和對話的場域,也著力於探討影視傳媒與都市生活之間的關聯性,以及影像本身的政治內涵。16 直到 2017 年停辦為止,歷經八屆的「OK. VIDEO」,已逐步確立了錄像藝術在印尼當代藝術史的重要性。17 這種匯聚集體的創作能量和組織民眾論壇並行的方式,同樣運用在 2004 年,ruangrupa 開始定期為學生籌劃的展演活動「Jakarta 32°C」當中。於是,每一屆參與「Jakarta 32°C」的年輕創作者,便得以在思考藝術之公共性與實驗特質的過程裡,持續地更新學院相對保守的創作風氣。ruangrupa 在地網絡的「節點」,除了民眾、學生、贊助單位和展演機關之外,也包括印尼各地的創作者。例如 2010 年,ruangrupa 創始人之一艾德即以「修復者」(FIXER)之名,串聯起 17 個替代空間和藝術團體。他認為「修復者」不只突顯出當代印尼集體創作行動之社會實踐的內涵,當創作者在面臨生存挑戰時,亦能透過相互扶持與連結的網絡,改善在地藝術產業之基礎建設的貧弱體質。18 藉此,我們可以清楚理解,ruangrupa 組織當代藝術網絡的目標,即為一種以「集體之共同體」(collective of collectives)來創建藝文生態的理想。19 於是,2015 年 ruangrupa 便協同 Serrum 和 Grafis Huru Hara,齊力在機構框架和經濟模式的社會實驗中,開展出集體創作的生態網絡 Gudang Sarinah Ekosistem,並隨後在 2018 年,轉型為著重於教育面向的Gudskul。

友誼與共存的難題

藉由寇克蘭「通信體制」的觀點來看 ruangrupa 二十幾年來的展演經歷,我們可以理解到,組織網絡作為其發展至今的集體創作方法,一方面精準地展現當代藝術全球化生產模式的樣貌,另一方面,也揭示了結合節慶、論壇、展覽、放映會和工作坊等各類型活動的多元展演形式,已成為今日迅速拓展連結之主要媒介的現象。不過,與此同時,對 ruangrupa 而言,組織網絡在印尼當代藝術史的脈絡當中,其實是具有相當特殊的時代意義:它標示著印尼的藝術團體從過去追求獨立自主的理想,走向當前永續互助的具體行動,以及從昔日抵抗極權的行動主義(activism),轉為實現共存生態之集體主義(collectivism)的歷史進程。20 因此,Gudskul 的講題協調者貝托.圖坎(Berto Tukan)即認為,當今印尼藝術團體的創作實踐所反映的,正是「關於共同生活的社會實驗」。21 但回望ruangrupa組織網絡的創作生產模式,所謂「互助」、「共存」和「共同生活」在其藝術行動裡,究竟形構出何種關係質地?艾德在 2012 年的訪談中曾提及,組織網絡就如同建立友誼一般,是一種有機、自發且開放的交互關係;隨即,他便強調,建構網絡也意味著一種政治行動。22 然而,此處我們可以繼續追問的是,如果當代藝術之關係網絡的質地和內涵,同樣與節點間資訊傳播的頻率和連結的強度有著緊密的關聯性,那麼艾德在組織網絡時所試圖開展的友誼和政治能量,又會在這其中產生怎樣的變化?

寇克蘭透過分析「通信體制」的特性,更深入地點出,當代藝術在信息傳播效應的影響下,創作者的作品與展演活動,不再是如大眾所慣常認知的和「藝術本質」(substance de l’art)或「美學內涵」緊繫在一起。23 今日當代藝術所處的現實,更多是關於信息網絡內各種符號的生產與消費、關於科層社會之量化的價值體系,以及關於靈活、流動與密集的人脈關係。換言之,創作者曾經篤信的美學價值,如今恐怕早已消解在綿密的網絡連結之中,並且被置換為利於傳播、推送和轉貼的影像資訊與文化符號。當然,面對這樣的美學泡沫化或商品化的現實,我們或許不必因此過度悲觀,甚至犬儒地推斷,所謂「友誼」不過是裙帶關係的潤飾之詞,而「共存」仍舊只能再製相互取暖和壁壘分明的同溫層。若以這樣的滑坡論調來看 ruangrupa 組織網絡的創作行動,很可能無助於釐清他們嘗試在文件展裡孕生的美學內涵或關係質地。但話說回來,寇克蘭當代藝術網絡的論述,確實描繪出當今藝術世界之生產模式的真實樣貌,而掌握這個現實基礎之後,我們也才能更嚴謹地去思辨友誼和共存之政治能量實際變異的情形。

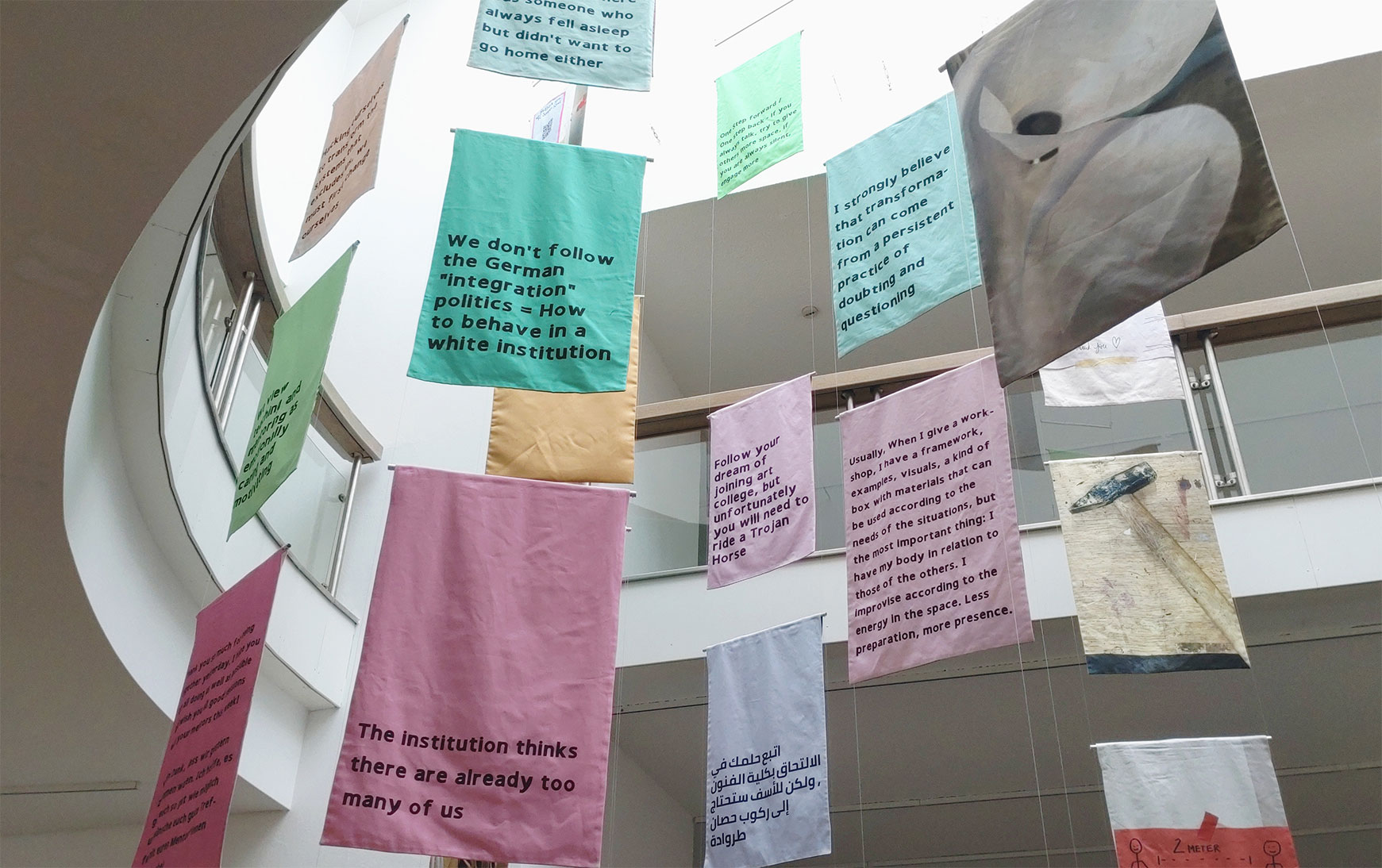

回望這次文件展位於弗裏德里希美術館(Fridericianum)的作品,丹.佩約夫斯基(Dan Perjovschi)在圓柱上所寫滿的穀倉價值24、*foundationClass 藝術團體懸掛於室內中庭的各種關於抵抗策略的旗幟,以及散佈在 Fridskul 牆面上的概念藍圖,皆透過醒目的字樣、強烈的對比色彩和獨特的圖像語彙,為此次的展覽帶來令人印象深刻的視覺效果。然而,風塵僕僕走訪於各展場之間的觀展群眾,如果欠缺展內活動的參與經驗或田野式的深度觀察,在此情況下,除了鮮明的視覺符號和 hashtag 般的標語外,可能很難感受到佩約夫斯基回饋羅馬尼亞在地藝術網絡的緊密連結25、或是理解 *foundationClass 與移民社群共同形成的組織動能,還有 Fridskul 共享知識的集體創作活力。這些在「原初」即被預設為緊扣住作品的美學價值,即便能經由展覽相關活動或偶發事件而獲得開展,其中連結與互動的質地,卻難免也會隨著關係網絡之樹狀譜系的結構,逐漸從主幹到末端,產生親疏層次的差異和變化。也就是說,和佩約夫斯基同組的穀倉藝術家,即得以在定期的小型會議(mini-majelis)上,與之產生緊密的交流和建立共享資源的合作基礎。此間,ruangrupa 為核心參與者所設計的網絡組織模式,不僅能彰顯具體的跨地域之連結,也在「節點」頻繁互動的過程中,創造出友誼豐富的質地與團結互助的強度。相對地,對一般觀者來說,不管是因緣際會地來到弗裏德里希美術館的穀倉起居空間與藝術家一起吃飯閒聊,還是參加 CAMP 論壇和 Gudskul 工作坊,或是在港口街 76 號展場(Hafenstraße 76)的夜間派對裡和陌生人喝酒跳舞,這些觀展體驗,終究很難脫離內嵌於國際大展之體驗經濟的生產消費模式。於是,一陣酒酣耳熱之後,觀眾、藝術家、策展人或許不再區分你我,但陶醉在愉悅感裡的同時,群眾開展真實連結與形塑共同體的政治潛能,亦逐漸消弭在友誼與共存美好的迷霧之中。

共同體的內在張力

5 黑森邦林管單位在活動的報導裡,轉述了現場植樹人員的抱怨:「這是藝術還是垃圾?」(Ist das Kunst oder kann das weg?)。請見:HessenForst, “Unser Wald – Fit für den Klimawandel,” HessenForst, 2021/11/29. https://www.hessen-forst.net/unser-wald (Accessed 2023/01/02).

6 這160位來自於德國和印尼多所大學的學者,因長期觀察蘇門答臘低地熱帶雨林的生態多樣性,而共同組成了學術研究平台EFForTS。此外,在第十五屆文件展期間,EFForTS也特別在哥廷根大學內,為「永續村落計畫」籌設研究成果展。請見:Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, “Research and Art Connect for Sustainability – a Cooperation Between the CRC 990 and the University of Göttingen with documenta fifteen,” Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, 2022. https://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/658092.html (Accessed 2023/01/02).

14 除了 ruangrupa 和阿姆斯特丹皇家藝術學院之外,首批加入 RAIN 的藝術團體包括墨西哥的 Los Mutantes 和 Guias Latinas、印度的 Open Circle、阿根廷的TRAMA 以及非洲的 Centre Soleil d’Afrique 和 PULSE。Thomas J. Berghuis, “Ruangrupa: What Could Be ‘Art to Come’,” Third Text, vol. 25, 2011, pp. 401.

16 The Collective Eye ed., The Collective Eye: In Conversation with Ruangrupa, Berlin: DISTANZ, 2022, pp. 52-53.

在展覽本身的網絡結構之外,ruangrupa 與德國的藝文、社會和政治機構的權力關係,在 2022 年初延燒至展覽後期的反猶爭議當中,亦成為討論本屆文件展相當重要的議題焦點。尤其,巨幅繪畫《人民的正義》(People’s Justice)的反猶圖像所引起之展覽議題失焦的現象,不只是單純反映出當代藝術網絡之信息傳播效應的典型徵候──亦即,去脈絡化的視覺符號和泛政治化的極端言論,遮蔽了作品和展覽內在的美學價值與意涵。主辦單位、策展團隊和藝術家面對爭議時的回應方式,也促使人們反思創作者在當代藝術混雜的「機構叢結」(institutional complex)內,如何建構與藝術機構之間的關係質地?而以組織共同體為理想的集體創作行動,又如何在機構網絡開展出共存的政治與美學內涵?針對這些難題,我們可能還是會因襲歷史前衛藝術的論述傳統,一味地臧否藝術機構消極、保守的行事作風,或簡單地將藝術機構的官僚文化與藝術家追求自由的抵抗精神對立起來。但如此一來,創作者在機構網絡裡所能孕生之社會變革的潛能,便很容易因此被忽略。如果藝術家在今日充滿隔閡、分歧和對立的社會中,就像艾德所認為的「中介者」(mediator)28,那麼,我們或許可以再進一步觀察,創作者究竟能以何種方式,聯合同樣作為中介角色的藝術機構,來嘗試創造出層次更豐富的網絡與異質的關係質地。

27 安巴赫是由穀倉成員ZK/U邀請到卡塞爾參展的眾多藝術家之一,其計畫的主要目標,在於串聯起分別居住在卡塞爾東區11個地點左右的居民,並期望藉此建構出反思全球化市場經濟的在地知識網絡。同時,藝術家也規劃了城東漫遊路線,以邀請觀展民眾和居民相互交流和學習。若以安巴赫的計畫內容來看,一方面根植於福達河(Fulda)右岸的這些在地知識,和位於左岸的文件展所強調的國際論述,確實產生鮮明的對比,另一方面,當地社群長期經營的生態與社會資源,亦具體地在文件展的資源框架外,呈現出在地連結和共存實踐的真實樣貌。例如,有機商店MILA、社區花園Blüchergarten,還有都市農產實驗中心SOLAWI Gärtnerei Fuldaaue所共同組成的農作社群網絡,即是透過與福達河氾濫平原(floodplain)緊密結合的生態耕作、責任消費和社區互助行動,發展出一套迥異於文件展生產模式的在地循環經濟。於是,安巴赫的「風景」計畫,得以藉由卡塞爾既存的社群網絡,突破文件展的樹狀關係結構,進而彰顯出在地之各種生態連結的關係質地。然而,安巴赫在路徑導覽、田野研究的成果展和相關的社區活動中,是否能夠因此推動社群和社群之間更緊密的友誼關係?或者,此計畫能否在與荷內.崔伯(Renée Tribble)之都市計畫研究團隊的合作下,偕同居民開展出改造生活環境的政治能量?「風景」計畫之集體創作的美學特質,似乎仍需要時間來慢慢觀察。EINE LANDSCHAFT, 2022. https://eine-landschaft.de (Accessed 2023/01/13). 此外,關於ruangrupa以ruruHaus為基地所建構的卡塞爾生態網絡,請參見:documenta fifteen,“Local Cooperations in Kassel – the Program of Kassel’s Ekosistem at Ruruhaus,” Documenta Fifteen, 2022.08.30. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/press-releases/local-cooperations-in-kassel-the-program-of-kassels-ekosistem-at-ruruhaus/ (Accessed 2023/01/13).

畢莎普在關係質地的美學分析裡,首先援引了拉克勞(Ernesto Laclau)和墨菲(Chantal Mouffe)政治哲學的觀點,強調「敵對」(antagonism)關係是形成民主社會的必要元素,它既是多元政治的構成條件,卻也標示出組成異質共同體的界限。29 然而,畢莎普的論述重點,並非全然聚焦在敵對關係之上,而更多是關乎形成異質社會關係的內在矛盾與張力,以及群眾在其中持續主體化的狀態。因此,作為中介者的藝術家,在串聯起經常被壓制的抵抗能量與異見時,其創作行動,便得以在組織各種互動情境與交互關係的過程裡,「維持」(sustain)異質共同體的內在張力。30 ruangrupa 的法里德.拉昆(Farid Rakun)在談論印尼藝術團體反體制的性格時亦指出,若單純聚焦在敵對關係是不足的,唯有在批判的當下做出改變、創造差異,我們才能在困境中開啟新的可能性。31 印尼今日的集體創作實踐,正是透過既敵對、批判且又合作和對話的連結組織方式,維持著跟政府單位、藝術機構、補助機關,乃至於和民眾之間的張力,因而得以開展共存的協商平台與多元的關係網絡。換言之,維持異質共同體的內在張力,絕非堅守著敵對關係和製造社會衝突。或者更準確地說,維持張力的藝術,即意味著藉由對立、失衡的情境,創生出重建生態連結與重構自我的契機,並同時讓組成異質共同體的政治能量,免於在二元對立的僵局和相互毀滅的災難裡消亡。從這個觀點來看,或許我們可以說,維持異質共同體的張力,在根本上,其實直指著維持友誼關係的張力,亦即一種批判和創造、對立和照護並存的創造性張力。是以,如何持守著朋友之間創造性的張力?此一提問,不僅能更加辨明集體創作行動之政治能量的強度,也能更深入地釐清創作者與機構共存的關係質地與內涵。

反猶的「迴力鏢」之後

最後,讓我們再回頭思考本屆文件展的反猶爭議。ruangrupa 在展前便不斷強調的「穀倉」(lumbung)實踐,對印尼傳統社會來說,除了關於儲備糧食和共享資源外,還包括凝聚社群、傳承文化知識,以及建構共存的生態倫理關係。32 這意味著,穀倉作為創造多重生態連結的場域,人們必須持續地在協商和形塑共同體的過程中,維持與他者和萬物之間異質且具有張力的關係質地。不過,穀倉共同體的內在張力,也會在不同的社會場域和情境中產生改變,並促使人們探求不同的協商策略和維持張力的途徑。於是,如幽靈般緊隨著文件展的反猶爭議,便立即地透過不曾歇止的敵對關係,突顯出從印尼轉譯到德國的穀倉實踐,不但需要更長的時間來組織在地的關係網絡,同時也須更進一步拓展出持守共同體之張力的集體創作行動。然而,這麼說並非意圖否定 ruangrupa 和參展藝術家在承受一連串的質疑、審查和攻擊後,挺身捍衛多元、平等和創作自由的努力。這些以聲明、連署,甚至退展的抗議行動,確實都有其必要性。但在另一方面,面對德國保守的藝術機構、民粹式語言的媒體炒作和反動的政治氛圍,集體創作實踐所能展現的政治能量和異質共同體的張力,難道只能單方面被文化機構規訓的手段和散播仇恨的聲浪所瓦解?如果ruangrupa在策展之初所揭橥的目標──以多元的夥伴關係直面差異和歷史的創傷33,即意指著維持異質共同體的創造性張力,那麼共存的集體創作實踐在德國的「機構叢結」內,究竟還有哪些可能性?

法証建築(Forensic Architecture)的創辦人艾爾.魏茲曼(Eyal Weizman)在評論《人民的正義》的反猶圖像時,藉由鄂蘭(Hannah Arendt)和塞澤爾(Aimé Césaire)省思二戰災難的觀點,指出歐洲的反猶主義隨著多年的殖民擴張後,卻在今日全球化的時代,以印尼解殖作品之反猶圖像的詭異樣貌,返回輸出母國。34 他認為此般自食惡果的現象,正體現了兩位政治思想家所說的「迴力鏢」(boomerang)效應。35 即便展出含反猶圖像的壁畫,實屬稻米之牙(Taring Padi)和策展團隊的疏忽,但其中反猶和殖民的「迴力鏢」效應,則實實在在地透過印尼與德國雙方的歷史創傷,於此次文件展激撞出深刻的關係質地,也精準地展現了當代藝術之「機構叢結」裡的政治與社會張力。是以,反猶爭議真正考驗 ruangrupa 的地方,與其說是他們風險調控和策展管理的技術與能力,不如說,更關乎穀倉網絡能否帶有批判意識地彰顯和轉化歷史迴旋的力道,並在與機構相互斡旋、合作,以及與群眾對話和修復的連結過程中,維持住異質共同體的創造性張力,進而開展出新的共存路徑與軌道。於是,卡塞爾文件展之後,穀倉網絡將如何延伸、如何拓展?ruangrupa 又能否從更深刻和緊密的在地網絡連結當中,引起實際的體制變革?甚或面臨自身的消解?這些ruangrupa在未來所衍生的各種可能路徑,都將能夠讓我們持續地以「關係質地」的美學視角,深思集體創作實踐的永續性,及其生態倫理行動的多重意涵。

27 安巴赫是由穀倉成員ZK/U邀請到卡塞爾參展的眾多藝術家之一,其計畫的主要目標,在於串聯起分別居住在卡塞爾東區11個地點左右的居民,並期望藉此建構出反思全球化市場經濟的在地知識網絡。同時,藝術家也規劃了城東漫遊路線,以邀請觀展民眾和居民相互交流和學習。若以安巴赫的計畫內容來看,一方面根植於福達河(Fulda)右岸的這些在地知識,和位於左岸的文件展所強調的國際論述,確實產生鮮明的對比,另一方面,當地社群長期經營的生態與社會資源,亦具體地在文件展的資源框架外,呈現出在地連結和共存實踐的真實樣貌。例如,有機商店MILA、社區花園Blüchergarten,還有都市農產實驗中心SOLAWI Gärtnerei Fuldaaue所共同組成的農作社群網絡,即是透過與福達河氾濫平原(floodplain)緊密結合的生態耕作、責任消費和社區互助行動,發展出一套迥異於文件展生產模式的在地循環經濟。於是,安巴赫的「風景」計畫,得以藉由卡塞爾既存的社群網絡,突破文件展的樹狀關係結構,進而彰顯出在地之各種生態連結的關係質地。然而,安巴赫在路徑導覽、田野研究的成果展和相關的社區活動中,是否能夠因此推動社群和社群之間更緊密的友誼關係?或者,此計畫能否在與荷內.崔伯(Renée Tribble)之都市計畫研究團隊的合作下,偕同居民開展出改造生活環境的政治能量?「風景」計畫之集體創作的美學特質,似乎仍需要時間來慢慢觀察。EINE LANDSCHAFT, 2022. https://eine-landschaft.de (Accessed 2023/01/13). 此外,關於ruangrupa以ruruHaus為基地所建構的卡塞爾生態網絡,請參見:Documenta Fifteen,“Local Cooperations in Kassel – the Program of Kassel’s Ekosistem at Ruruhaus,” Documenta Fifteen, 2022.08.30. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/press-releases/local-cooperations-in-kassel-the-program-of-kassels-ekosistem-at-ruruhaus/ (Accessed 2023/01/13).

分享