– The Visceral Economy of “Avant-Garde”

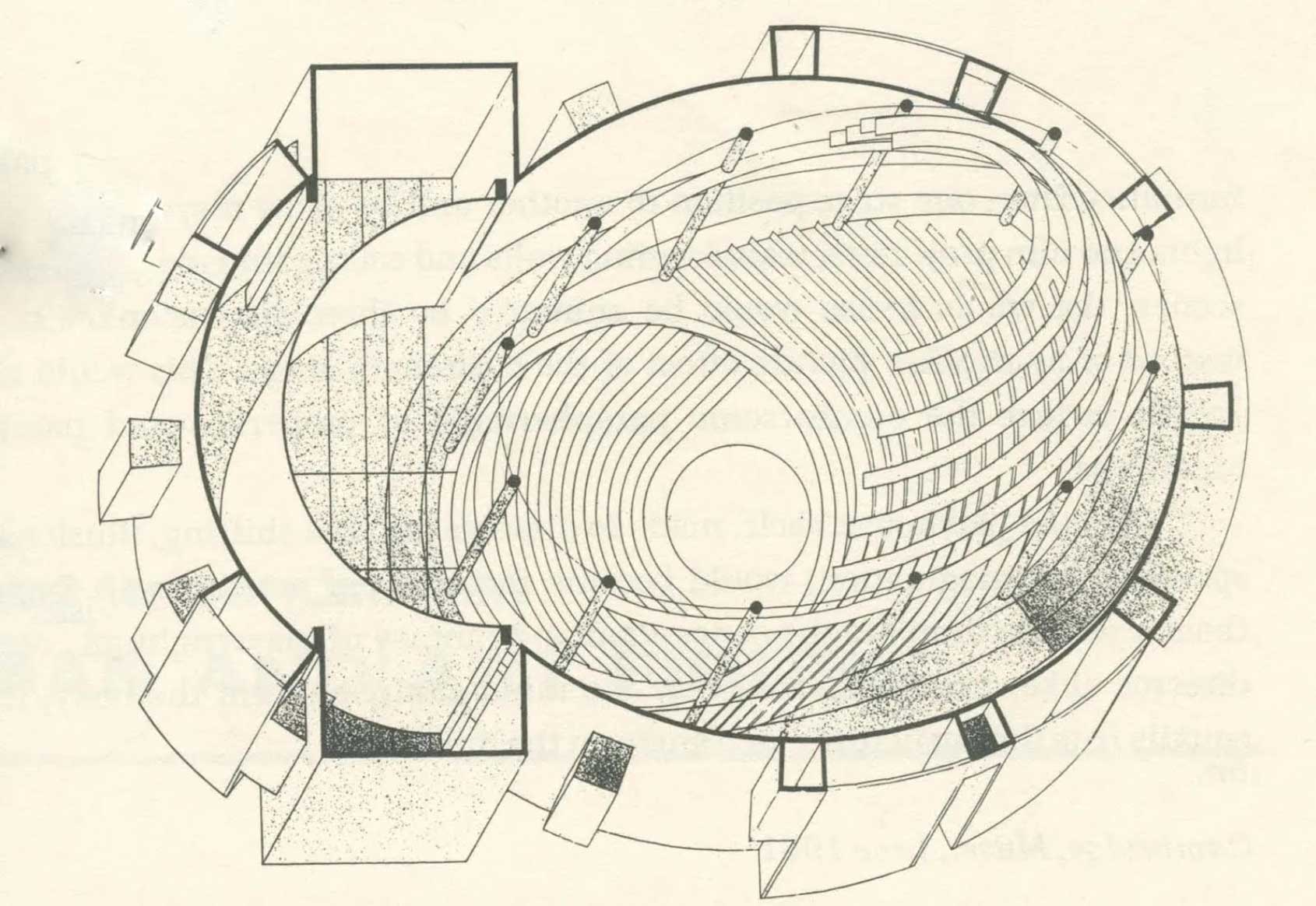

It is intriguing to imagine Bauhaus founder, architect Walter Gropius, and theater director Erwin Piscator sitting together in 1927, pondering the sketches of their shared vision of the “Totaltheater” (lit. “total theater”). They hoped to create a theater that could break free from the rigid structures of the conventional proscenium stage and combine different stage models within a single, dynamic space. Gropius’s solution was a rotating and mobile platform that could change the audience’s perspective mid-performance. Beyond the mechanical innovation, he envisaged the integration of light and film projections to expand the theatrical space and intensify the experience (Fig.1). Already a pioneer in the fusion of theater and film, Piscator saw this as the perfect opportunity to “activate” audiences and transform urgent social issues.1 Despite their ambitious visions, the avant-gardes of the Bauhaus would not have imagined that Taiwan would realize this utopian concept for a stage venue almost a century later.

With the Taipei Performing Arts Center (臺北表演藝術中心, TPAC), a building has emerged combining both Gropius’s and Piscator’s “Totaltheater” model and Andor Weininger’s “Spherical Theater” concept – the latter emerging at the Bauhaus during the same period. TPAC, which officially opened in August 2022, represents a significant step in Taiwan’s broader vision to enhance its cultural infrastructure.2 This contribution explores what has constituted TPAC’s venue concept, from its nomadic years under a Preparatory Office, until the completion of its construction, considering TPAC’s hosting of the Taipei Arts Festival (臺北藝術節) and ADAM (Asia Discovers Asia Meeting for Contemporary Performance, 亞當計劃-亞洲當代表演網絡集會).

The “Avant-Garde” Emergence of TPAC

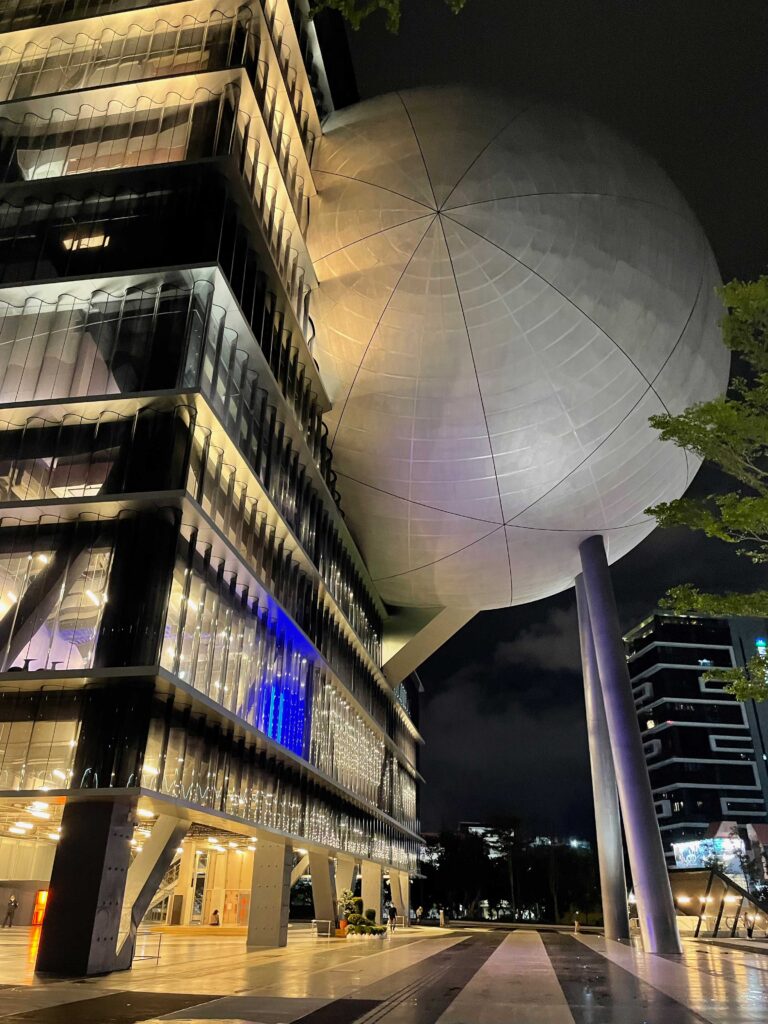

Walking through Taipei’s Shilin district, one is struck by the TPAC’s distinctive shape, which has inspired a variety of symbolic interpretations, with many locals likening it to pidan doufu (皮蛋豆腐), a popular local dish of cold slices of silken tofu served with a preserved, dark-coloured “century egg.” To familiarize the public with the design, architect Rem Koohlhaas (Office for Metropolitan Architecture, OMA) who worked in collaboration with Kris Yao (姚仁喜, ARTECH) has also drawn comparison to a three-broth hot pot, linking the architecture with local cultural imagery, particularly that of the nearby Shilin Night Market (Fig.2).3 Embracing the idea of its local rootedness and translating it programmatically, into an ethos of being “Open For All,” TPAC has positioned itself as an “Asian co-production center” (亞洲共製中心) and an “urban art theater” (城市藝術劇院), carving out a distinctive role in regional production networks.4

4 See Taipei Performing Arts Center, 112 nian yusuan shu 112年 預算書 [2023 Budget Book]. Taipei: Taipei Performing Arts Center, 2023. Accessed March 22, 2024. https://tpac.org.taipei/information-2.

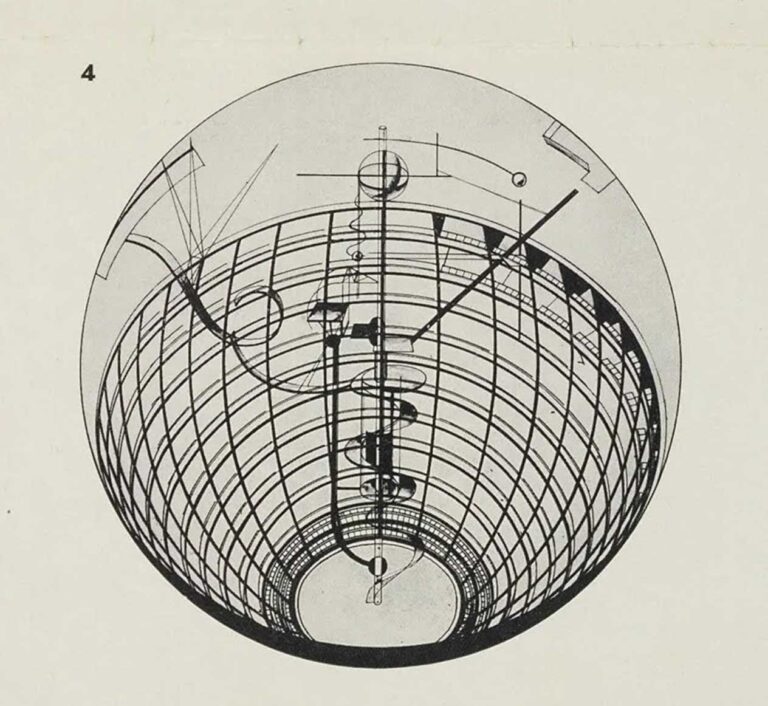

The venue houses a “3+1” spatial concept, with one circular and two block-shaped structures extending in different directions from its main body.5 It is designed to allow the audience to engage not only with the performances on stage, but also with the production process itself – challenging notions of spectatorship by placing the stages, rehearsal and production spaces at the core of the building, with auditoriums protruding to the sides. To allow the public to witness “how the theater is used,” the architects designed a special “public corridor” “Public Loop”) that winds around the three theaters. This “loop” may have been inspired by the Sherling Backstage Walkway of London’s National Theatre in order to offer a glimpse of the technical support and backstage.6 The stages of the Grand Theater and Blue Box at TPAC can be linked together to form the “Super Theater” (超級大劇院), an architectural configuration reminiscent of the expansive dimensions of the Totaltheater (Fig.3). TPAC’s third major stage, the Globe Playhouse, carries a Shakespearean name but draws further on Bauhaus-inspired theatrical models – OMA seems to have been influenced by Weininger’s 1927 design for the “Kugeltheater” “Spherical Theater”), which Weininger described as a response to the Totaltheater. It was presented as another speculative model, influenced by nomadic circus troupes and Greek amphitheaters, without further discussion of its potential realisation (Fig.4).7 Other spherical concepts that have left their mark on a history of unrealised theater architecture and may have been given consideration include Étienne-Louis Boullée’s design for the Paris Opera and Frederick J. Kiesler’s “Endless Theatre” (1959–1961), laconically called “The Universal: An Urban Theatre Centre.”8

With regard to the concept of the Totaltheater, it is easy to misinterpret Gropius’s declaration of the attainment of the “totality” of the stage. Rather than reflecting the expansion of the technical, mechanical potential of theater, the potentiality of totality is contextualized in his belief in “gestalt thinking” and its philosophical potential, articulated in his rhetoric at the time, along with terms such as “synthesis,” “unified,” “cooperation,” or “collective.”9 For this relatively early period, the Bauhaus ideas about the stage were highly experimental, placing the body itself at the center of artistic research and attempting to provide direct access to lived experience.10 However, since the crux of modernism, with which the Bauhaus and its artistic visionaries are usually associated, is a claim to universality, thinking in terms of “multiple” and “liquid” modernities and pluri-potentialities, one might ask: is it significant that TPAC’s architectural concept refers to a European historical avant-garde movement?11 The implications of this question is further underscored by the open space of the ”Super Theater,” which evokes historical forms of East Asian performance cultures and suggests a potential relearning, or healing of the Western proscenium stage model.

TPAC’s Development and Identity

Delving into TPAC’s ambitious development, the venue was conceived during a period of significant cultural investment under the “Ten New Major Construction Projects Policy” (新十大建設), introduced by Taipei Mayor Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) in 2004. Political changes and competition between the municipal and central governments significantly affected the project’s progress. Although originally scheduled to be completed in 2013, construction did not begin until 2012. The project suffered another critical setback in 2016 when the main contractor declared bankruptcy, nearly doubling the budget to more than USD $200 million. Additional complications arose from political reservations about integrating the theater with the adjacent Night Market, highlighting tensions between cultural inclusivity and the desire for a prestigious architectural landmark.12 Undoubtedly, a symbolic sense of competition with the National Theater and Concert Hall (國家兩廳院, NTCH), Taipei’s largest theater complex to date, also influenced the planning, as TPAC’s Grand Theater was not to accommodate a larger audience than the National Theater. In addition, TPAC’s color scheme, nicknamed “Beiyi Blue,” was apparently chosen to contrast with NTCH’s unique red (Pantone 1797C), which is prominent throughout NTCH and its corporate identity.14

Under these circumstances, the process of defining TPAC’s identity and mission already began during the construction phase. Contrasting with Taipei’s existing theaters, TPAC, also known as “Beiyi” (北藝, meaning Northern Arts Center), arrived with the intention of signaling a shift in artistic production and articulating a prioritization of artistic processes and needs, which further resonated in its approach to curation and production. Under Austin Wang (王孟超, Wang Meng-chao) as Director of the Preparatory Office, the construction postponement was reframed as a strategic opportunity, allowing the institution to establish artist and audience relations and its international network. In an interview, Wang observed that despite the setbacks, the extended timeline permitted TPAC “to communicate and take root.” Therefore, the period from 2017 to 2022 was pivotal in shaping TPAC’s management framework and operational protocols, ultimately establishing it as an Asian co-production house and a hub for experimental artistic creation.15

In 2017, as part of its strategic initiatives to nurture emerging artistic talent and cultivate a professional network for the future, TPAC, together with artist-curator River Lin (林人中), launched ADAM (Asia Discovers Asia Meeting for Contemporary Performance). Aligned with the Taipei Arts Festival and held annually in August, ADAM draws inspiration from regional models of performing arts meetings,16 but sets itself apart by embracing the concept of an “artist meeting,” implemented through a three-week artist residency format known as Artist Lab, where former participants take on the role of guest-curators.17 Following the residency, the ADAM Gathering invites international professionals to Taipei, where the Lab artists present work-in-progress performances, accompanied by numerous networking activities (Fig.5). The artist-led initiative provides support for both local and international artists, diverging from existing models by fostering long-term collaborative opportunities for works that can be toured internationally. In Taiwan, ADAM has since become the longest-running platform of its kind.18

In 2018, TPAC expanded its networked influence by assuming responsibility for the organization of the Taipei Arts Festival, the Taipei Fringe Festival (臺北藝穗節), and the Taipei Children’s Festival (臺北兒童藝術), consolidating its role in reshaping Taiwan’s performance ecology and extending its international reach. From 2019 onward, Lin has additionally collaborated with TPAC on the curation of Camping Asia, a workshop program aimed at students and emerging professionals. This initiative promotes inclusive exchanges among artists from Europe, America, and Asia and has strengthened TPAC’s collaborative ties with its project partner, the French Centre national de la danse.19

TPAC’s emphasis on a networked international outreach distinguishes it within the competitive landscape of Taiwan’s major cultural venues. Amidst established ones with distinct profiles such as the NTCH, the Taiwan Traditional Theater Center (臺灣戲曲中心), and the newly completed Taipei Music Center (臺北流行音樂中心), TPAC has emerged as a versatile platform that encompasses a broad spectrum of artistic expressions beyond conventional theater and musical formats. Its programming includes experimental works, dance performances, and interdisciplinary collaborations, appealing to a more diverse audience base and attractive to reciprocal international collaborations. The early expansion of its programmatic scope within Taiwan’s traditionally rigid, genre-based performing arts ecology was supported by the vision of its initial leadership team: From 2020 until early 2024, TPAC was guided by Taiwan’s renowned theater director Liu Ruo-yu (劉若瑀), who served as Chairperson, and senior stage designer Wang, who moved to the position of CEO – artistically inclined individuals with extensive knowledge of the local arts ecosystem and experience in international outreach through touring. They were joined by Singaporean curator and dramaturge Tang Fu Kuen (鄧富權), as curator of the Taipei Arts Festival from 2018 to 2022, and Lin, as curator of ADAM and Camping Asia, shaping TPAC during its formative, literally “avant-garde” years.20 Following the completion of a three-year term by Liu and Wang, TPAC appointed a new leadership team in January 2024. Wang Wen-Yi (王文儀, Victoria Wang), who recently served as the artistic director of the National Taichung Theater and has previously served as director of Taipei Arts Festival (2008–2011), assumed the role of Chairperson, and Wang Shiyin (王詩尹), who has held various roles in Taipei’s arts administration, including the Taipei Children’s Art Festival, became the new CEO.21 Such refocus on a management-driven approach certainly marks a departure from TPAC’s earlier artist-led directive. Ideally, given TPAC’s success in shaping intra-Asian performance networks, particularly through the Taipei Arts Festival and ADAM, there will be a continued commitment to artist-led programming and collaborative formats.

Redefining the Role of the Curator in TPAC’s Institutional Framework

From 2017 until 2022, as the Shilin venue was under construction, both the Taipei Arts Festival and ADAM operated as urban nomads, taking place in various public venues in Taipei City.22 Tang and Lin prioritized artistic exploration over conventional, formulaic approaches and standardized production formats – supporting “research and development” (研究及發展) to suggest performance-based practices as a lens for exploring societal issues in the context of democratic Taiwan and the broader East Asian region. Based on conceptual proposals and curator-artist dialogues, this nomadic period was characterized by work-in-progress development cycles that often tested different spatial and temporal settings of different presentation venues, tailored to the specific needs of each artistic work.23 In 2023, in addition to his ongoing role as ADAM’s curator, Lin was appointed as the first artist-curator of the Taipei Arts Festival, following Tang. Lin’s inaugural festival program, entitled Dancing Ecosystems (萬物運動), took a radically experimental, cross-genre approach, bringing together artists from both the visual and performing arts.24 The curatorial proposal aimed to transform the newly opened TPAC into an immersive gathering space to challenge established conventions and hierarchies in performance production. In contrast to the spatial explorations of Dancing Ecosystems, Lin’s 2024 program, Embodying Theirstories (時間博物館, lit. “time museum”), delved deeper into issues surrounding Taiwanese and East Asian theater history. By emphasizing time as a central element of theater, the program maintained a playful and innovative spirit while also demonstrating a shift toward more conventional programming strategies for TPAC’s large auditoriums.

Balancing Avant-Garde Aspirations

Since the completion of the venue in 2022, TPAC has shifted to a more centralized production model with a prominent architectural presence. In view of the Taipei Arts Festival and its related programs, this change has concentrated both personnel and financial resources and altered its operational dynamics, aligning more closely with institutional protocols and the venue’s proscenium structures.25 This dynamic underscores a fundamental tension within TPAC’s contemporary identity: while the venue is ostensibly “Open for All” and supports a wide range of genres, from musicals to traditional Taiwanese opera, the annual festivals and curated programs need to remain concentrated on innovative and experimental practices.

Reflecting on the programs discussed, TPAC’s “avant garde” period might hence be characterized as an era of conceptual curation. Therein, Lin’s and Tang’s work has played a crucial role in cultivating the institution’s “meta-economy,” a vibrant community of artists and professionals across the region and beyond – expanding the role of the performance curator to include significant structural responsibilities, prompting a rethinking of presentation modalities and networking strategies. In Taiwan’s settler-colonial context, where issues of colonial history, ethnic diversity, and ideological urgency converge, curating and artist-curating particularly involves fostering constellations that illuminate the local-global spatio-temporal conditions under which performance is produced, as well as the mechanisms and formats that facilitate its visibility. This aspect mirrors broader shifts in a contemporary performance ecology, which, similar to the avant-garde of Germany’s Weimar era, grapples with the pressures of economic viability and ever-shifting political expectations.26 The models of the Totaltheater and the Kugeltheater, which have influenced TPAC’s design, fundamentally reflect the idea that perspective is central to world-making. In contrast to “functionalism,” the ideal often associated with the Bauhaus since the 1970s, these concepts acknowledge a vision of a deeper socio-aesthetic transformation that this artist-led institution stood for – notes for a future in which the Super Theater awaits its full exploration, both curatorially and artistically.27 By reimagining the performance space as a site of “gathering,” as embodied in the idea of “total” or “super” theater, there is, indeed, potential for restorative and new forms of pluri-connectivity.

1 See Gropius, Walter, “Vom modernen Theaterneubau, unter Berücksichtigung des Piscatortheaterneubaus in Berlin [On Modern Theater Construction, with Consideration of the Piscator Theater Construction in Berlin],” in Knut Boeser and Renata Vatková (eds.), Erwin Piscator. Eine Arbeitsbiographie in 2 Bänden, Bd. 1 (Berlin 1916–1931) [Erwin Piscator: A Working Biography in 2 Volumes, Vol. 1 (Berlin 1916–1931)]. Berlin: Edition Hentrich, 1986, 148–149. See also Lichtenberg, Drew, The Piscatorbühne Century: Politics and Aesthetics in the Modern Theater After 1927. Milton Park. New York: Routledge, 2022.

2 It is part of a new generation of “performing arts centers” (PACs), including the National Taichung Theater (臺中國家歌劇院), and the National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts (衛武營國家藝術文化中心, nicknamed Weiwuying), which have been open to the public since 2016 and 2018, respectively.

3 See Kornblatt, Izzy,” Drama Queen: OMA’s Taipei Performing Arts Center Floats Above the City, Promising New Possibilities for the Making of Theater,” Architectural Record 210 (2022): 60–67, 66.

4 See Taipei Performing Arts Center, 112 nian yusuan shu 112年 預算書 [2023 Budget Book]. Taipei: Taipei Performing Arts Center, 2023. Accessed March 22, 2024. https://tpac.org.taipei/information-2.

5 This configuration includes a 1,500-seat Grand Theater, an 800-seat Globe Playhouse, and an 800-seat Blue Box, all integrated into a cohesive layout.

6 It is also worth noting that not only TPAC’s ground floor provides space for (public) performances, but up to six rehearsal spaces on the upper floors can be used for public showcases. In addition, other public spaces on the first and second floors may potentially be transformed for performances.

7 From 1925 to 1928, Weininger was a member of the stage workshop and played a key role in the Bauhaus dances. He designed the Kugeltheater for the opening of the Bauhaus architecture department in 1927. See bauhaus 3/1927 –special edition“bühne” [stage] of the Bauhaus journal.

8 See Frederick J. Kiesler, “The Universal,” in: The American Federation of Arts (ed.), The Ideal Theatre: Eight Concepts (New York: The American Federation of Arts, 1962), 93–94.

9 See Walter Gropius’s 1923 essay “The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus.”

10 This aspect may have prompted RoseLee Goldberg to place the Bauhaus stage in the history of performance art and the avant-garde in 1977 – a context in which its theatre artists are still often viewed. See RoseLee Goldberg, “Oskar Schlemmer’s Performance Art,” Artforum, 16.1 (1977): 32–37.

11 … as attempting to discuss Taipei’s new performing arts center through the lens of the “avant-garde,” and to transplant this primarily Euro-American concept into the Taiwanese context, may seem a challenging and, given a history of asymmetric international co-production experiences in Taiwan, redundant exercise. See Lei, Daphne P., “Interruption, Intervention, Interculturalism: Robert Wilson’s HIT Productions in Taiwan.” Theatre Journal 63, no. 4 (December 2011): 571–586.

12 See Goudsmit, Inge et al., “A Performing Arts Centre for Whom?: Rethinking the Architect as Negotiator of Urban Imaginaries,” Urban Studies 61, no. 2 (2024): 350–369.

13 See National Theater and Concert Hall, “NTCH – A Cultural Icon in the Performing Arts World.” National Theater and Concert Hall (NTCH). Accessed April 15, 2024.: https://npac-ntch.org/about/introduction/duty.

14 Austin Wang, interview with the author, Taipei Performing Arts Center, August 29, 2023.

15 Initiatives that emerged during this period include the Musical Theatre Training Project (TPAC 音樂劇人才培訓計畫), which started in 2016, ADAM in 2017, Camping Asia in 2019, and the Circus Factory (馬戲棚計畫) project in 2020.

16 Reference models include the Performing Arts Market in Seoul (PAMS) held alongside the Seoul Performing Arts Festival (SPAF); the Australian Performing Arts Market (APAM) associated with the Adelaide Festival and RISING Melbourne; and the Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting (YPAM).

17 On ADAM’s activities and development until 2021, see Lin, River, ed. Networked Bodies: The Culture and Ecosystem of Contemporary Performance. Taipei: Taipei Performing Arts Center, 2022.

18 ADAM conceptually builds on earlier institutional initiatives such as the Huashan Living Arts Festival (華山藝術生活節, 2010-2013) and the Taiwan Performing Arts Connection (表演藝術國際交流平台, later renamed CO3, 2015-2017), which paved the way for establishing links between Taiwan and international performing arts markets. In addition, ADAM’s initiator Lin credits local artist-led initiatives such as the Taiwan International Performance Art Festival (台灣國際行為藝術節, TIPAF), founded in 2000 by Wang Mo-Lin (王墨林), for inspiring the concept of ADAM. Additionally, since 2021, NTCH has initiated the biennial Taiwan Week, linked to the Taiwan International Festival of Arts (台灣國際藝術節, TIFA).

19 The project “Camping” that inspired “Camping Asia” was initiated by Mathilde Monnier during her directorship at the CND in 2015.

20 In this context, it is interesting to consider another parallel with Erwin Piscator and the establishment of the Piscator Studio at the Theater am Nollendorfplatz. This pioneering initiative employed collectivist pedagogical methods that bear resemblance to TPAC’s ADAM Lab and Camping Asia projects.

21 See Taipei Performing Arts Center, “Taibei biaoyan yishu zhongxin di 2 jie dong jian shi mingdan gongbu wang wenyi ren di 2 jie dong shizhang zhixing zhang you wang shiyin churen 臺北表演藝術中心第2屆董監事名單公布 王文儀任第2屆董事長 執行長由王詩尹出任 [The list of directors and supervisors of the Taipei Performing Arts Center for the second term was announced. Wang Wen-Yi was appointed as the second chairman. Wang Shi-Yin was appointed as the CEO].” Taipei Performing Arts Center (TPAC) January 31, 2024. https://tpac.org.taipei/news/255.

22 Venues where ADAM presented its program before settling into the TPAC include the Taipei City Hakka Cultural Park and the Dadaocheng Theater. The festival has used venues such as the Zhongshan Hall, Metropolitan Hall, Wellspring Theater, Umay Theater in Huashan 1914 Creative Park, or on the campus of the Taipei National University of the Arts, among others.

23 Examples, among other projects, include a series of collaborations between Formosa Circus Art (福爾摩沙馬戲團, FOCA) and Filipino artist Leeroy New – which began with their first meeting during ADAM in 2017 and developed as part of ADAM’s work-in-progress format “Kitchen” in 2018, before being shown at the festival in 2019; and the development-cycle preceding The Landless Events (不知邊際,不知所謂事件) by the Ghost Mountain Ghost Shovel collective (鬼丘鬼鏟), which opened the 2022 festival at Zhongshan Hall. After presenting working-stage pieces during the 2019 and 2020 TAF (VX, The Library Tapes), which explored various personnel constellations and conceptual avenues, The Landless Events took over the theater with a complex interplay of live art-inspired physical exhaustion and durational narration, coupled with elements of filmic, mediated liveness.

24 These included Chen Yu-Dien’s (陳煜典) and Feng Cheng-Tsung’s (范承宗) The Rite of Lobster (脫殼), Lee Ming-Chen’s (李銘宸) and Luo Jr-Shin’s (羅智信) Louver/Shutter/Blinds/Hundred Leaves (百葉), as well as the experimental series Concert for Plants (給植物的音樂會) that presented artistic collaborations on the TPAC’s roof garden.

25 The relocation has further highlighted some social limitations inherent in the center’s architectural design. Although TPAC has spacious, daylight-filled rehearsal studios, it also faces practical problems, such as narrow elevators, which suggest that the upper floors were not designed to accommodate large groups of visitors. In addition, the lack of temporary residency spaces for visiting artists or curators suggests that TPAC adheres to a traditional “performing arts center” model that closely follows the conventions of “Western theater” – focusing primarily on representation, exhibition, and performance – rather than embracing a broader role as a community gathering space.

26 In balancing more conservative year-round programming with initiatives such as the Taipei Arts Festival and ADAM, decisions are increasingly driven by the need to meet revenue targets and increase the venue’s self-financing rate in relation to public funding. This underscores the broader challenge of sustaining artistic innovation within institutional frameworks, as artistic research and inquiry will inevitably confront the very infrastructure of the institution with questions of its politics and sustenance.

27 Thus far, the Super Theater has been used only in commercial contexts: Taipei Fashion Week transformed the space for a runway show in autumn 2022, and the THEATRE TECH EXPO (劇場技術展) in March 2024 also used the spatial model. Both events allowed those present to move freely around the space, recalling the alternative name of the Gropius-Piscator model, also called “Raumtheater” (“space theater”), in the sense that there is no spatial separation between performers and audience.