In a sense, the broadest question of ethics is really about what a good life is, and how to live it. However, feminists have found that even within such a wide range of issues, in mainstream ethics, the moral significance of interpersonal relationships is always ignored, while excessive attention is paid to people’s independence, autonomy, rights and freedom, even as intimacy and love with others are neglected, and marginalized groups, such as children, the elderly, and the disabled are more typically excluded.3 Feminists’ ethical viewpoints have turned to relationalism, not simply to focus on the ethics of small-scale intimate family relationships, but to consider closely the ethics and political philosophy of how “the individual is politics,” and at the same time, to criticize contemporary ethics and political philosophy. Feminism argues that contemporary ethical and political philosophy focuses too much on the redistribution of material wealth and not enough on other aspects of oppression. Therefore, it is believed that we should broaden the scope of ethical concerns, in order to retrace the political back to the felt significance of the personal.4

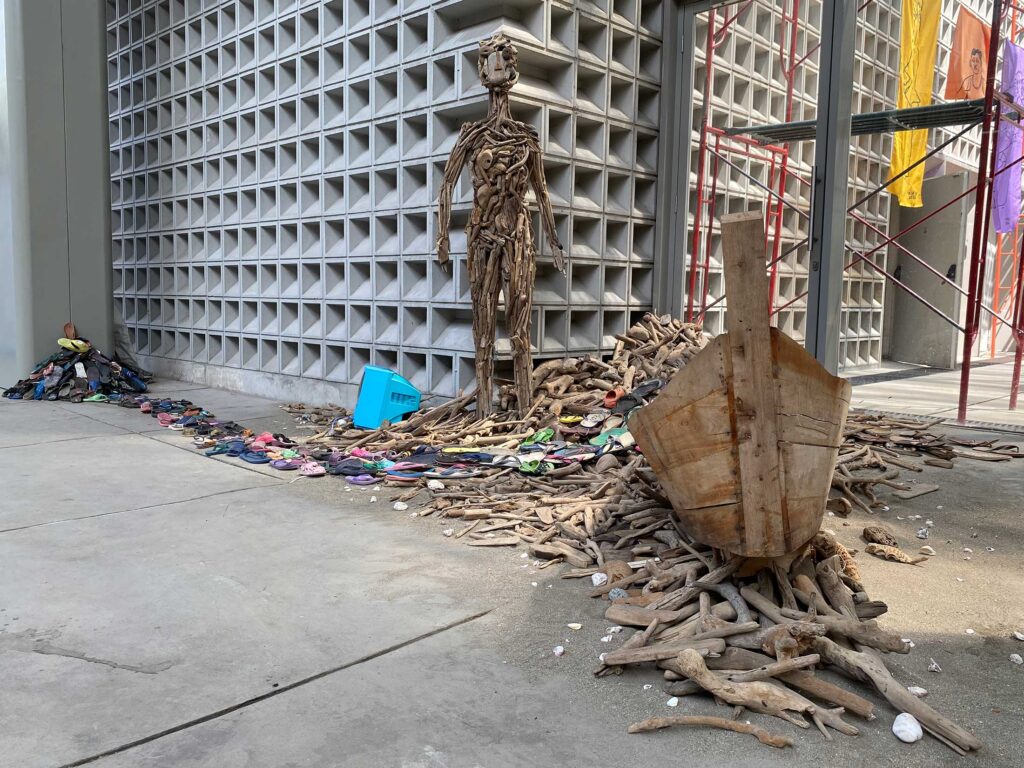

From the point of view of the political nature understood by Arendt in the sense of the polis, the potential of its aesthetic practice is added to the above-mentioned natality and pluralism, plus the creation of a city-state that provides the space for speech and action. To put it another way, the political potential of public space in Arendt’s work is the aesthetic potential of an artistic topography to create spaces that have the capacity of natality and pluralism. Arendt also warns us that “The modern growth of worldlessness, the withering away of everything between us, can also be described as the spread of the desert…….the human world is always the product of man’s amor mundi, a human artifice whose potential immortality is always subject to the mortality of those who build it and the natality of those who come to live in it. What Hamlet said is always true: ‘The time is out of joint; O cursèd spite / That ever I was born to set it right!’ In this sense, in its need for beginners that it may be begun anew, the world is always a desert……On the contrary, they are the anti- nihilistic questions asked in the objective situation of nihilism where no-thingness and no-bodyness threaten to destroy the world.”<sup>16</sup> Perhaps in a world that is gradually deserted, we can look back at the ancient Roman origin of the word “culture” as analyzed by Arendt. According to her research, culture is derived from the ancient Roman word, “colere,” which has the characteristics of cultivating, dwelling, taking care and preserving. It means that people interact with nature through cultivating and caring until a livable place is created. It can be seen from this aspect that the Romans regarded art as a kind of agriculture and cultivation of nature, while the Greeks tamed and ruled nature in a formidable way. Perhaps it’s time for us to rethink the Roman legacy, and think about how to create a livable place with the artistic concept of caring for nature. This may be the aesthetic glimmer of artistic topography in the desert.

15 Ibid., p. 477.