Exhibition Amnesia

The initial oral traditions had to decease to ensure

the survival of mankind, and the course of history

mandates that written language gradually replaced

its predecessor: the ancient oral world.1

If there is no meaning in art, then what is art for? It is self-contradictory to claim that there is the art of no meaning while deliberately refusing to acknowledge meaning, a refusal that ultimately renders itself insignificant. In other words, even in the absence of someone to speak with, art must still function as a language system, capable of conveying meaning and intentionality through its signs. For instance, in the Sin City,2 where theaters involve no living actors and the spectators only witness the active agency of devices and machines, it is still an act of performativity that subjects humans to the non-human, instead of the other way around.

In relation to Okwui Enwezor’s Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, in 2008, and Hal Foster’s discussion of “An archival impulse,” Tino Sehgal emerges as a subversive figure: his opposition to the archive, regardless of its medium, is to go against the grain of art being a mere visible and material-based archive. Sehgal believes that the archive and visibility are conspicuously intertwined. However, since the end of the last century, the forces of post-colonialism and cultural decolonization have been in a full swing, showing in the polyphonic writings of anti-Western art history and its centrism, which increasingly emphasize the recovery and archiving of documents, the proper preservation of pertinent artifacts, and the recalling of memories inseparable from regional local histories. In contemporary art production, archives have also gained emerging critical potential and enchanted aesthetic appeal, allowing artists to present “ignored, resisted, or suppressed historical facts” to spectators, as Hal Foster later describes for the archive impulse. What is presented is not a trite unsurprising display of information, but rather a “complex composite” of writings, audio-visuals, or objects, often in the form of installations, with spatial attributes that are “non-hierarchical” or expressed as “time ready-mades.”8 As for these artist archives, they cannot be normalized in nature, whether they are excavated, of obscure origin, or fabricated, yet contemporary artists often present them with a “gesture of alternative knowledge or counter-memory,” shifting the focus from formal, chronological history to “minor historical materials.”9 In this context, Hal Foster alludes to the works of Tacita Dean, Joachim Koester, and Thomas Hirschhorn regarding their manipulation of archives. They treat the archive as the spatial and temporal representation of a historical era, wherein “branches and shoots extend out, much like weeds or rhizomes,” undergoing a “transition of connection and disconnection” through the aforementioned methods.10

At a curious moment, could it be that Tino Sehgal is dedicated to revitalizing oral culture, viva voce, within a contemporary art paradigm that is evolving away from traditional archives? Let’s consider the scenario in which he utilizes archives or documents, but, in line with his usual practice, strictly prohibits himself and others from archiving his own work. What happens then? Is Tino Sehgal’s work a mere provocation? Or, is Tino Sehgal’s work just a storm in the teacup of archives? What, then, if the storm is the implosion of signification, as what Jean Baudrillard describes, can the word of mouth, viva voce, in turn damage the archive?

While many contemporary artists advocate for the deconstruction of archives, Tino Sehgal’s approach of relying on word of mouth is even more radical. He discards the concept of traditional archives and keenly prohibits the creation of archival materials. In contrast, other artists’ attempts to disrupt the metalanguage of archives often leave them confined within a merely linguistic game, even when employing subtle and sophisticated methods. In other words, Sehgal’s abandonment of the archive goes beyond what Foster describes as an “an-archival impulse.”11 Sehgal is more concerned with the traces and obscurity of his work than with the certainty of signifiers, as his art exists within the exhibition space like floating signifiers, constantly expanding and inflating. This allows for the unpredictable retelling of narratives associated with his work. Therefore, Sehgal’s work, considers the origin lost from the very beginning, along with the unresolved plots, thus offering only a musing depth that provides aesthetic meaning as the consolation prize. There remains a lingering shadow of doubt, persistently eliminating all manipulations of archival metalanguage. Sehgal is, paradoxically, an author outside the archive but deeply involved with it, enclosed by it, and has carried the debates on the archive to an extreme. He cites art historians to support his work. The first, Didier Maleuvre, strongly criticizes the umbilical connection between museums and industrial society. He argues that the fetishism of objects is sufficient to compel the masses to bow before them, forsaking their religious culture, as he contends that people no longer experience the same divine subjectivity that once defined religious culture. The second historian, Dorothea von Hantelmann, considers that the experience of art, with a particular emphasis on inter-subjectivity, transcends the traditional production of subjectivity for contemporary art. She underscores the primacy of the conceptual immaterial want over the physical material need, a central aspect of the aesthetic paradigm since Minimalism, granting new status to the formation of visual art. Lastly, Tony Bennett advocates for the establishment of “civic laboratories” within art museums. He emphasizes their proactive role in driving social change, adopting a tone akin to political negotiators. Through research, Bennett encourages an exploration of the relationship between people and objects, prompting the generation of new agendas within the institutionalized cultural field and revitalizing the museum from both within and without.12

It is like a pair of the Sehgal twins, the uncanny doublegangers, in the superposition state of quantum physics. What I intend to convey is that his presence within the archive resembles a lingering specter, drifting and haunting with the persistent reverberation of his word of mouth insisting on oral delivery as if there is an endless echo within the in-between spaces of the archive cabinets. The implosion I mentioned earlier is no longer confined to the interiority of events; instead, it seems to open outward like a gaping mouth, voraciously consuming everything, akin to a black hole that swallows everything, marking the death of the archive. In other words, to embrace the more aggressive Sehgal twin is to follow it all the way, as if to reverse the temporal construction, evoking a complete subversion of orality that obliterates all archives in the violence of spirituality, resembling the gravitational collapse of a dying star. It goes without saying that within this embrace, memory is lost, and conversely, amnesia persists indefinitely.

Undoubtedly, it’s not an easy task, but expanding upon Tino Sehgal’s oral word-of-mouth approach is highly worthwhile when examining contemporary art, especially within the context of global indigenous contemporary art. The significance of this topic cannot be overlooked; it is, in fact, crucial. Taiwan is no exception to this; particularly indigenous cultural themes have gained immense prominence in recent years, as they concur with the ecological concerns prevalent in the global art world and academia, especially in the post-pandemic era.

In the case of Ami artist Lafin Sawmah’s Fawah, a canoe carved from China Berry wood, a sequence of three exhibitions occurred between 2020 and 2021, all well situated within the framework of curatorial discourse. These exhibitions took place in the following order: The Real People Series – Crouching, Standing, Sitting, and Lying, featured as part of the 2020 Pulima exhibition held at the Sanjianwu Collective in Taitung; Hatch, A Dream at the Far Edge exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, both curated by Akac Orat (Hao-Yi Chen). Finally, at the Library venue of C-Lab, there was an exhibition titled Mapalak Tnbarah Folding Roads — The Fusion of Pulima Art Festival, co-curated by Dondon Hounwn and Lovenose. These three exhibitions unveiled the work-in-progress of Fawah at different stages: in the Pulima exhibition the work took the form of a simple boat placed on a platform; in C-Lab the artist added some paddles, which hung on the wall. As a work of art, its journey was far from over.

In 2023, at the Taitung Museum of Fine Arts, The Sound of the Waves is So Loud, co-curated by Gong Zhuojun, Huang Chingying, and Li Yunyi, showcased Fawah in a new form. It was set with a straw hut placed outside the museum’s existing sand platform. The boat itself was equipped with an additional “outboard pontoon” for stability, realizing Lafin Sawmah’s dream of sailing the canoe over the sea. In fact, the refurbished canoe had been successfully launched in the previous year for the ceremony witnessed by the local tribesmen and the Hawaiian navigator Kimokeo.13

As the work Fawah travels through different exhibitions, it responds to Hongjohn Lin’s observation that the work of the Turkish artist Can Altay, which blends with its exhibition history, is often accompanied by overlooked interpretive discourses. Lin argues that “exhibition amnesia is a necessary part of any curatorial apparatus,”14 while the symptom must persist until transference takes over, and often, unfulfilled desires can manifest as forgetfulness in Freudian terms. However, Fawah deviates from this symptom because the agenda of ethnos-aesthetics is ingrained in the cultural field of indigenous contemporary art and curatorial practice, which helps prevent epistemicide.15 The long-suppressed cultural aphasia of indigeneity, in the process of self-reconstruction and self-fabrication, focuses on memory recovery and archiving, the essential cultural strategy of identity politics. Notably, Manray Hsu and Etan Pavavalung’s cocurated exhibition, The Distance Between Us and the Future – Taiwan Indigenous Contemporary Art (2021), serves as an effort to archive indigenous contemporary art. The Indigenous Cultural Park represents a contemporary fusion of Walter Benjamin’s ritual and exhibition values, with the institution serving as a guardian. An intriguing case is the work of Amis artist Ruby Swana. She chose to exhibit her artwork at the Tsou fraternity, a site typically designated for men’s gatherings, as she needed to be granted permission by the tribe’s approval, based on her ethnicity and gender. This settlement was not documented in the Tsou’s written consent or related materials; it was purely a verbal agreement, solely belonging to the realm of oral culture. The work itself is a manifestation of orality: coins for ritual cups, iron mesh, and reflective paper wrapping around the building’s wooden columns and stones with leaf-shaped patterns that reimage the trunks and leaves of the surrounding trees. The reflective paper extends to the leaves in the form of fragmented specks, shimmering in the forest’s darkness at night on the site of the supposed muscularity.

In the contemporary world, the connection between exhibition and ritual is often contingent, as the case with Fawah, which ultimately takes a tragic turn. Seven days after the opening, Lafin Sawmah temporarily removed the canoe from the exhibition site to participate in the tribal sea festival and to go fishing in the sea. Tragically, he drowned. Only after the funeral ceremony could the work, the canoe, return to the exhibition site after several days of absence from the venue. As suggested by the title of the work, Fawah (meaning to navigate the path), his art is deeply rooted in orality, embodying the oral tradition of the Amis people of Austronesian languages, who once built canoes for long-distance voyages; nowadays only bamboo rafts are used for offshore sailing. According to Lafin Sawmah, the process of building a canoe for long-distance sailing is more about “speculation than recollection,” as he avoids getting entangled in the trap of Eurocentric archaeology and anthropological survey.16 Fawah represents an assemblage of wild thought, a reimagining of a lost tradition and a reinvention of it as a work-in-progress bricolage.17 It was assisted by friends from various ethnic groups and experts, including Huang Guangde, a boat builder from the Tao tribe of Orchid Island, and Kimokeo, a canoe navigator from Hawaii. Lafin’s tragic death interrupted what could have been a work looking towards the future for possible narratives and cultural vocabularies. It’s important to note that Fawah can be seen as a variation of Lafin Sawmah’s 2018 work Deer Path, a site-specific installation at Busan Art Residency in South Korea, in its topological relations; both works represent a ritualistic reimagining of the paths of animals. As curator Akac Orat describes, the canoe is one of the vehicles through which Lafin Sawmah sees himself “becoming a man.”18 The work, along with the artist’s life, represents a convergence of becoming both human and animal, mirroring each other’s subjective positions in ecological practice.

What makes the work Fawah an archival object? While Huang Chingying has explored the inherent animism of indigeneity and the importance of the canoe, as well as the phenomenological perspective on corporeality, we must also consider the role of cultural production within the Asian context. In contrast to the Occidental historical process, particularly since the European Renaissance, where humanism played a central role, the interplay between art and craft in Asia follows a different cultural trope. In many cultural regions across Asia, decolonization and contemporary cultural transformation tend to adopt a quick fix approach, often shaped by the self-identity imposed by the big Other. I firmly believe that indigenous cultures should be vindicated from such critique: the paths of decolonization are intricate, multifaceted, and ever-emerging, making it impossible to oversimplify the complexities of decolonization into mere black-and-white terms. Moreover, the metalanguage of the work Fawah doesn’t merely refer to the conditions of its production in linguistic terms. It transcends classical semiotics that often regard static images and enunciations as paradigms. Instead, it gains the status of transdisciplinarity through being framed in several exhibitions since its emergence in 2020, as the metalanguage of the work can even be traced back to the very beginnings of Lafin’s art projects, dating to when a massive pile of driftwood was found in the aftermath of Typhoon Morakot in 2009. This situation led to the gathering of a group of prominent indigenous artists, nurturing a unique atmosphere of discourse among them, reflecting on the conditions of the ecological crisis.

Like any linguistic act portending as much as art, when it unfolds, it gives birth to its own metalanguage, following like a shadow that never leaves. When this metalanguage remains shrouded in the mist, it serves not only as a reflection of the past but also as an oracle to a possible future. Consider the case of Lafin Sawmah: had his precious life not been tragically cut short, we can only speculate about what his artistic metalanguage might have become. If the artist transcends the boundaries of ethnos and indigenous identity and if his work had broken free from the confines of curatorial contexts to become part of a distinct discursive formation, we must acknowledge that curatorial amnesia is not just about what was given in the past but that which grants a promise to the future. Hence, I resist pigeonholing “archival objects” into any fixed category of identity politics, as Tino Sehgal’s radical approach prompts us to question the cultural politics of indigenous orality, while even in the global context, most indigenous languages, including those of Taiwan, are nowadays typically written in Romanized spelling systems. Firstly, concerning the war and the struggle of memory within archives, Arjun Appadurai presents a brilliant and concise argument in Archive and Aspiration.19 He suggests that archives, which encompass the interiority of the processing documents, represent a form of “meta-intervention.” Instead of viewing them as metaphors for the body or containers, it is better to regard them as “a base for emancipation projects” — struggle to bridge the gap between neuro-memory and social memory. Interestingly, Appadurai introduces the concept of “oral archives,” but he does not address the question of what memory would resemble if it were an invisible archive, independent of its visibility.

Secondly, concerning orality and literacy, Walter J. Ong, in his classic work 1982, conducted a meticulous examination of the interplay between orality and literacy in the technological age, adopting a non-dualistic and deconstructive perspective.20 Nevertheless, while emphasizing the importance of orality, if the oral archive can embody the aura of oral transmission as discussed by Walter Benjamin in The Storyteller, where “the trace of man is attached to the story,” and “the potter’s handprints is left on the clay vessel,”21 then in the context of the technological age, both current and future generations might anticipate a god-like memory, one that is all-encompassing and omnipresent both within and without. Would this entail dwelling in a timeless, anarchic hall of living memory, where the origins can no longer be recalled? This is not a far-fetched idea, especially when considering Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, with the allegory of “the maiden who offers the plucked fruits.”22 In this analogy, the artwork resembles the fruit plucked by the maiden from the tree. It’s cradled in her hand and meticulously cared for under her watchful eye, evoking the full life cycle of the fruit in the tree and nature itself. The maiden serves as a metaphor for the artist, and in modern times, also for the curator. Yet paradoxically, if we were to live in the hall of living memory, there would be no need to pluck the fruits of art.

This could be seen as a form of redemption in the sci-fi vein, just as much as a visible variant of orality. In 2016 film Arrival, the narrative is told with non-linear temporality and its memory of the writings of the aliens, a voice graphics. However, it’s not without its quirks and oddities, as is explored in Agamben’s masterful essay Origins and Forgetting, which references the legend of Victor Segalan.23 The tale begins with Térii, a troubadour who carries the words of his ancestors and serves as a guardian of the oral tradition as he walks around with a strand of braided cord, chanting over the fingertipped knots. This cord is known as “the source of speech” and has the power to enable a person to speak the language. However, the cord is lost one night to a chief named Paofaï, who leads the people in reciting incantations in Western script — a kind of writing on a manuscript that conceals the magic within symbols, and which they “look at each with their eyes before they communicate.” Here, the oral tradition pits against characters, literature, and the written word. The former is represented by the idea that “myth is the language without speech,” while the latter, by “literature is the speech without language.” Both culminate in a reunion and mutual redemption. The allegory concludes with the peculiar sequence of “mouth to mouth to the origin”: the severed head instinctively flies away, tumbles in front of the predator, and then returns to the origin. Segalen supplements this allegory with another narrative: an immortal man, whose head can repeatedly return to him, being reborn again and again, is portrayed as a singer, a god, or even an emperor. He dies and resurrects the following day in a repetitive cycle, amidst the witness of music and an individual who represents an ancestor.

Such an enigmatic and somewhat frightening scenario is grounded in the ideas of love, fervor, awareness of the world’s tumult and transformation, and at times, the capricious and uncanny nature of affinity. Even in the darkness, where the light remains uncertain and gloomy, it can still guide us on our solitary journeys, and we will finally encounter the “Lichtung,” a term coined by Heidegger in Off the Beaten Track. In the opening of the exhibition Return to Zero (2000), curated by Rita Chang at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Rahic Talif sang an Amis song with a resonant and crystalline voice. His installation work, Basalaigol/Return-to-Zero, devised two wooden pillars forming an arch as the entrance with a band of clay tiles on the ground created a circle, each bearing the footprints and names of the tribesmen. As soon as the singing concluded, Rahic Talif walked on these tiles, as if tracing the footsteps of the tribesmen, encircling the other pillar to complete the return-to-zero ceremony, going back to his own tribe. Long ago, the art critic Jiang Guanming recorded Rahic Talif’s words: “Go back to the origin, Face to the ancestral spirits, and the door will open… through an action, a voice, or a thought… where lies the power of returning-to-zero?”24

Returning to one’s origin is always a return to the foundation, necessitating the constant regeneration of the action itself. Every regeneration must be innovative, ensuring that what we call the “origin” is perpetually reborn. This, as it seems to me, is where the power of Basalaigol lies.

1 It is an adaption of Walter J. Ong’s writings. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (London: Routledge, 2002) 14.

2 Produced by the Center for Arts and Technology of the National Taipei University of the Arts in 2013, and co-created by artist J.J. Wang and the LuxudaryLogico new media art group, with video performances by Yi-Jing Lu, the show was performed at the Multimedia Hall of the Taipei Songshan Cultural and Creative Park from October 24th to 27th of that year.

3 Playwright Harold Pinter adapted John Fowles’ original novel (1969) into a movie script.

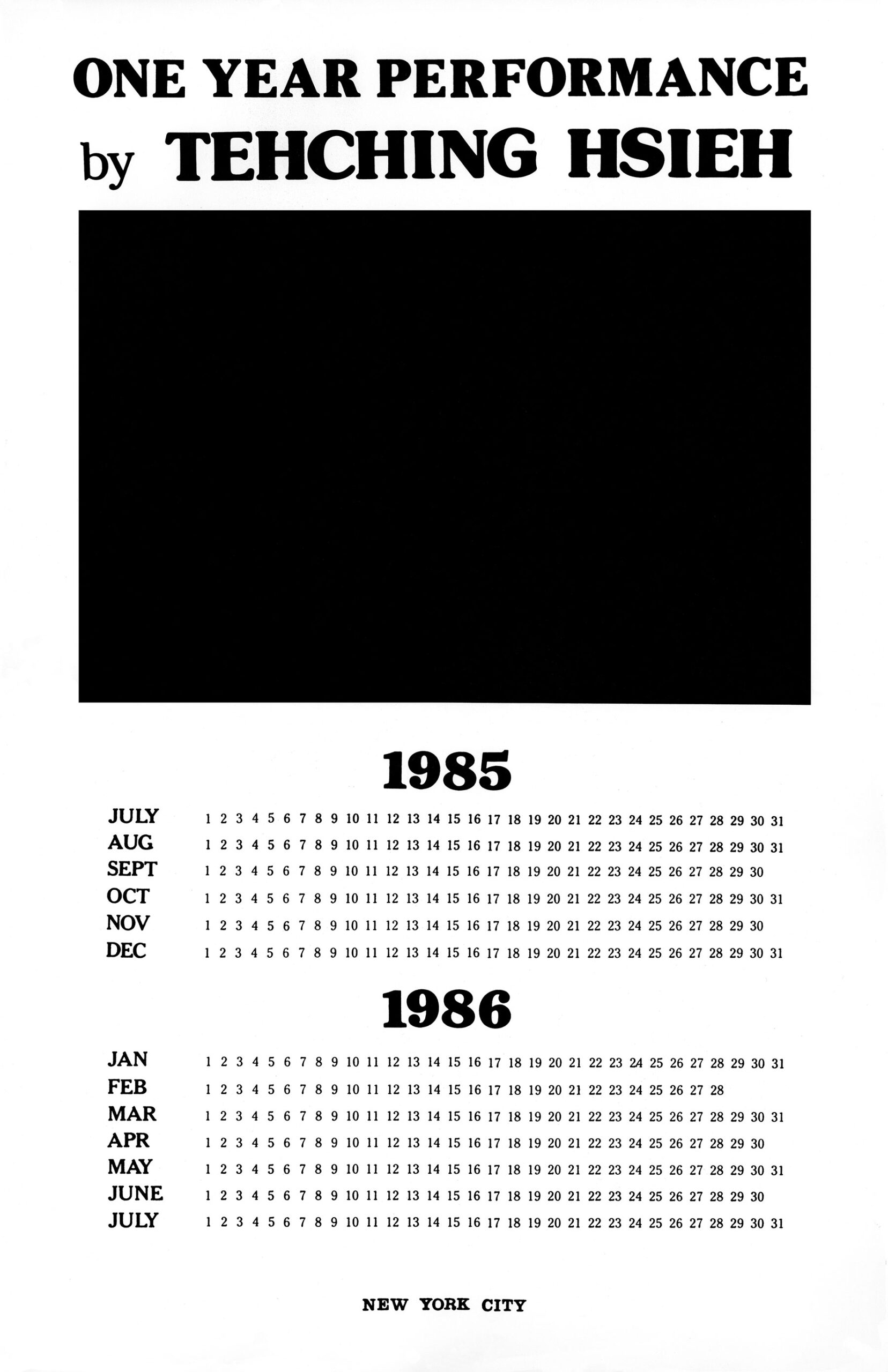

4 For the English version of this document, please refer to the website of the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, accessed Oct. 1, 2023, https://www.mplus.org.hk/en/collection/objects/tehching-hsieh-19861999-thirteen-year-plan-2013467/ ; For the Chinese t, see “Responding to the Rope of Consultation,” dictated by Li Qinqin and Hsieh Tehching, Artouch. 2017.05.01, accessed Oct. 1, 2023, https://artouch.com/art-views/content-1545.html.

5 The term is recognized by Tino Sehgal, see Towards the Age of Performativity: Performativity as Curatorial Strategy, Frorian Malzacher & Joanna Warsza, translated by Fei-Lan Bai, (Taipei: Shulin Publishing Company, 2021) 24.

6 For the usage of the term “discursive formation,” Foucault defines it as the regularity among statements, objects, performances, concepts, and so on. Foucault write, “To analyze a discursive formation therefore is to deal with a group of verbal performances at the level of the statements and of the form of positivity that characterizes them; or, more briefly, it is to define the type of positivity of a discourse.” Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Trans., A.M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon Press, 1972) 38, 125. from Michel Foucault, see L’Archéologie du savoir, Ed. Gallimard, 1996 edition, Paris, p.

7 On Tino Sehgal’s work, accessed Oct. 1, 2023, https://cmagazine.com/articles/collecting-forever-on-acquiring-a-tino-sehgal.

8 It is worth noting that Foster believes the artist as archivist follows that of the artist as curator, as they accept the museum’s decline in the public sphere and explore alternative systems. Archival art is more about institutional reformation rather than destroying or transgressing established norms. Hal Foster, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, and Emergency (London: Verso Books, 2015) 32-34.

9 Lee Xiangyu’s Chinese translation of the term “minor historical materials” as “the residue of historical material” is thought-provoking. Hal Foster《來日非善:藝術、批評、緊急事件》(重慶: 重慶大學出版社,2020) 38。

10 Hal Foster, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, and Emergency, 35.

11 Hal Foster, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, and Emergency, 40., 50.

12 Tino Sehgal on Tino Sehgal2010, accessed Oct., 2, 2023, https://www.artforum.com/features/tino-sehgal-194569/.

13The video of the sailing of the work, accessed in Oct., 3, 2023, https://news.ipcf.org.tw/52292.

14 The Exhibition Amnesia, accessed on Oct., 10, 2023, https://curatography.org/.

15 The Heterogeneous South, accessed on Oct., 10, 2023, https://curatography.org/

16 An interview done by Zian Chen, ARTFORUM, accessed Oct.,5, 2023, https://www.artforum.com.cn/interviews/14262.

17 This section is to a discussion of mode of thought and the poetic process of making and becoming. Claude Levi-Strauss, The Savage Mind, trans., George Weidenfeld (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1966) 15-17. — Tr.

18 “The Interview of Akac Orat,” Interviewees: Jiang Boxing and Wu Shangyu. Another Story: An Inquiry of Taitung Art (Taitung: Taitung County Government, 2022) 234-243.

19 Archive Public, accessed Oct., 5, 2023, https://archivepublic.wordpress.com/texts/arjun-appadurai/.

20 Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, 2.

21 Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, edit. Hannah Arendt, trans. John Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 2007) 92.

22 G. W. F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977) 456.

23 阿岡本,《潛能》,譯者: 王立秋、嚴和等(桂林:灕江出版社, 2014) 203-217;see also, Giorgio Agamben, Potentialities: Collective Essays in Philosophy, trans., Daniel Heller-Roazen (Sandford: Sandford University Press, 1999)

24 Reference to Jiang’s Blog on the artist performance, accessed Oct.,2, 2023, https://blog.udn.com/PASA9512/1117087

Share

Author

Tai-Sung Chen graduated from the Department Fine Arts of National Taiwan College of Arts with a speciality in western painting in 1983, and later graduated from L’École Nationale Supérieure d’Art de Cergy (Pontoise) in 1992. He is an assistant professor at the National Taipei University of the Arts, specializing in the history of painting, the history of contemporary Western art and art criticism. He was on the Reviewing Committee of the Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture, and in 2017-2019 he served as the Artistic director of Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture. He has contributed a number of essays to a variety of publications regarding the arts.

Sponsor