Introduction

I began writing this artistic chronicle on a chilly evening by the Mekong River after having the opportunity to visit the international contemporary art festival in Chiang Rai Province, or better known as the Chiang Rai Biennale 2023 (Thailand Biennale, Chiang Rai 2023). This art festival was supported by and collaborated on various groups of organizations and artists, including government agencies, private sectors, as well as internationally recognized and locally respected artists and curators. All of them aimed to promote Chiang Rai as a “City of Art.” The use of the word “Biennale” in Thailand refers to the art world whereby international art exhibitions are held every two years. The first Biennale was the Venice Biennale, which took place in 1895. The grandeur and beauty of that art festival examined many historical backgrounds and revealed many controversies, including the display of colonial power through aesthetic dimensions, the artistic power of imperialism, and the Western world facing structural changes after the Industrial Revolution.

Indeed, from this perspective, art festivals are not simply about showcasing beauty and promoting tourism. They also involve the “Aestheticization of politics,” which helps to conceal the political nature of things while simultaneously creating a new mode of perception within an aesthetic framework. The relationship between politics and aesthetics is a crucial factor in shaping our understanding of reality and our place in society. This is what is known as the politics of aesthetics.

Thailand’s adoption of the “Biennale” format is therefore particularly interesting. Of course, it is not an old tradition in the art world. The important question is: what is the significance of the process of establishing art as a cornerstone of the Thai state’s cultural work? This is especially true when we consider the spatial dimension, the historical and political background, and the meaning of contemporary art that emerges in this area, all of which are tightly interwoven.

The study of authoritarianism in Thailand has developed over many decades and has become widespread, especially in political science and historical research, which focuses on the study of political structural change and the role of political leaders.1 In contrast, studies of art history that link to social and political change are rarely mentioned in the academic community. Yet in fact, this kind of art history study is very deep and interesting, especially in trying to understand the role and work of Thai artists who are sending questions to the public through the process of art creation. David Teh, a scholar from the National University of Singapore, and Thasnai Sethaseree, a scholar from Chiang Mai University, interestingly proposed that in the 1990s, the Thai art scene experienced a great deal of tension between the “local” and the “global.” Thai artists became aware of and questioned globalization and modernization trends by incorporating cultural and traditional ideas into their artwork. Teh argues that on the surface, such work creates a dichotomy between the local and the global. However, deeper down, Thai artists had already been connected to global art, alongside their opposition to globalization, with nationalism as the backdrop. The most prominent and representative art festival of that era was “Chiang Mai Social Installation,” which created an art center outside of the capital of Thailand.2 However, the nationalism of Thai artists was like a seed that took root and grew vigorously in the body of artistic progress. This seemingly paradoxical relationship between nationalism and globalization allows us to understand that, on the one hand, nationalism in art has helped the art world ecosystem become more driven by capitalism, and hence artists have had more opportunities to connect with the art world through exhibiting and selling their work. On the other hand, nationalism in art did not lead artists to imagine freedom, but rather pushed many famous artists to agree with the coup and authoritarianism, especially the art movement between 2013 and 2014 called “Art Lane,” which aimed to eliminate representatives of “evil capitalism” and “authoritarian democracy” by supporting the military creating an absolute democracy with the king as head of state. This is in line with the mainstream nationalist ideology in Thailand.

For me, it is sad but true that the progress of Thai art in the 1990s has become a reminder of the glory of nationalist ideology, while at the same time, it has fallen short of its potential and can not continue to exist in the contemporary era. Its status is an artistic ruin waiting to be bolstered by an authoritarian regime. It therefore exists as an aesthetic and political contradiction in relation to the freedom of artistic expression in Thailand.

The coexistence and interdependence of art festivals and authoritarian regimes became increasingly evident after the coup d’état in Thailand. The Thailand Biennale, an international contemporary art festival, was first held in Krabi in 2018 and in Nakhon Ratchasima in 2021. Both editions were organized by the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture (OCAC) under the Ministry of Culture, which was led by the military government of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha. The status of the Thailand Biennale has therefore been a subject of considerable debate, particularly concerning the freedom of artistic expression and its incorporation into the mechanisms of political power and the legitimization of authoritarianism. The status of art, which emphasizes creativity and aesthetics, has thus become something that coexists with military bureaucracy and administration. Moreover, the Thailand Biennale has also become a key link to the international art world, with the invitation of renowned and respected curators and artistic directors. This can be seen as a new feature of authoritarian regimes that are turning their attention to soft power and the creation of a new image of the military government as being modern and contemporary.

This is made evident by the fact that contemporary Thai art has returned to a glorious time once again due to the patronage of the authoritarian regime. On the one hand, government support in various forms has given Thai artists more opportunities to showcase their work on the international stage, leading to an unprecedented level of vibrancy in the art scene. On the other hand, the tense political climate, the lèse-majesté law (Article 112), and restrictions on freedom of expression create obstacles for the creation of art that reflects social and political issues. A significant number of Thai artists choose to use art as a tool to fight for democracy and freedom. They utilize diverse art forms, such as performance art, graffiti, theater, and music, to communicate political messages and challenge authoritarian power.

1 Thak Chaloemtiarana, Thailand: The Politics of despotic paternalism (SEAP Publicationl, 2007).

; Soren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager, “Saying the Unsayable: Monarchy and Democracy in Thailand,” in NIAS Studies in Asian Topics (NIAS Press, 2010); Nattapoll Chaiching, “The Monarchy and the Royalist Movement in Modern Thai Politics, 1932 – 1957,” in Saying the Unsayable: Monarchy and Democracy in Thailand, ed. Soren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager, (NIAS Studies in Asian Topics, NIAS Press,2010).

2 David Teh, Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary (The MIT Press:2017).; David Teh and other authors, Artist-to-Artist: Independent Art Festivals in Chiang Mai 1992–98 (Afterall Books in association with Asia Art Archive and the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College: 2018).; Thasnai Sethaseree “The Po-Mo Artistic Movement in Thailand: Overlapping Tactics and Practices,” Asian Culture and History Vol.3, No. 1: 31-45.

In Thailand, the question of “what is art?” may be less significant than “how does art function?” and the further questions of who is it patronized by and by what type of ideology is it legitimized? If we close our eyes and think about the various artworks shown at the Thailand Biennale. We may find intellectual entertainment that such artworks transmit to the viewer’s world of thought and life, for example, the discovery of the visual pleasure of eating food for thought through the eyes. This would include discovering new economic opportunities with arts and cultural tourism as a stimulant. But can we still imagine other forms of art functioning beyond the approving eye of state support? The art of ordinary people and non-artists artworks that are not displayed at art festivals, but appear on the streets, and works of art which challenge authority in a straightforward manner, without intellectual sophistication, yet which are intellectually entertaining. Where do the artworks of these disreputable and arrested artists fit into the aesthetic imagination of Thai society? There are very few active Thai academics who have studied these provocative issues, such as Thanavi Chotpradit’s study of the censorship of contemporary Thai art in Thailand, that occurred in art galleries after the several coups in the past decade in Thailand and a study of the struggle of activists and artists in Thailand against the dictatorship of the military government led by General Prayut Chan-o-cha in particular.3 Such would include the fight in the lèse majesté case4, Pandit Chanrochanakit, which focuses on criticizing 1990s avant-garde artists in Thailand who supported the coup in the past decade, including Thanom Chapakdee (1958 – 2022), an academic who recently passed away.5 Thanom played a very important role in setting up a line of thought and artistic action that was not only a resistance to power but also helped to make art more democratic.

In Thai society, art is fragile and dangerous. Because art can silence and block viewers’ questions through the aesthetic process, the incorporation of artistic work into authoritarian regimes thus legitimizes the regime itself and helps set the aesthetic framework for which artworks should be supported and displayed. This political situation likewise brings into focus which works of art will most likely be prosecuted.

The Third Thailand Biennale in 2023, in Chiang Rai Province, was initiated and occurred in a completely different political context than the first two exhibitions. In particular, the awareness of Thai citizens towards the 2022 elections has stimulated an atmosphere of hope and an effort to create change at all levels. The “Politics of hope” emerged around election time and played an important role in opening spaces for many ordinary people to have the courage to express their opinions and political expressions. After being ruled under an authoritarian regime for a long time, at the same time, anxiety was growing among conservatives. The results of the election on May 14, 2022, were unanimous as in the past, as the military-political party led by General Prayut Chan-o-cha lost the election. However, unfortunately, the party that received the most votes, the Move Forward Party – พรรคก้าวไกล, could not form a viable government. As a result, the Pheu Thai Party – พรรคเพื่อไทย, the second-ranked political party, could successfully form a government under the politicians from the former authoritarian regime, who had joined the new government. Amidst this political volatility the Chiang Rai Biennale has done one of the most admirable things: presenting the voices of ordinary people seeking expression through the artistic process, which are thus enabled in this biennale.

I had the opportunity to meet and talk with Gridthiya Gaweewong, the artistic director of the Chiang Rai Biennale, many times. She emphasized on many occasions that representing the voices of ordinary people is essential to imagining national history and making rights and equality important in Thai society. Especially, this includes the voices from subaltern groups and those who are invisible in Thai history. Gridthiya says that the main reason she chose to work with Chiang Rai province as the venue for the event is because Chiang Rai is a border city. The status of border cities is unique in that they connect to countries in the Mekong subregion, a place of ethnic diversity, and a confluence of various types of economic and political power. This border city is also rich in stories of people crossing the border, immigrants and those undergoing diaspora, and is likewise known for the story of resistance to central state authority. In addition, the border area in Chiang Rai province has been known for a long time through the image of the Golden Triangle, which is filled with stories of drugs and the security of the Thai state that has been built since the Cold War. Therefore, presenting the stories of people from below is a significant part of creating a politics of hope through artistic work.

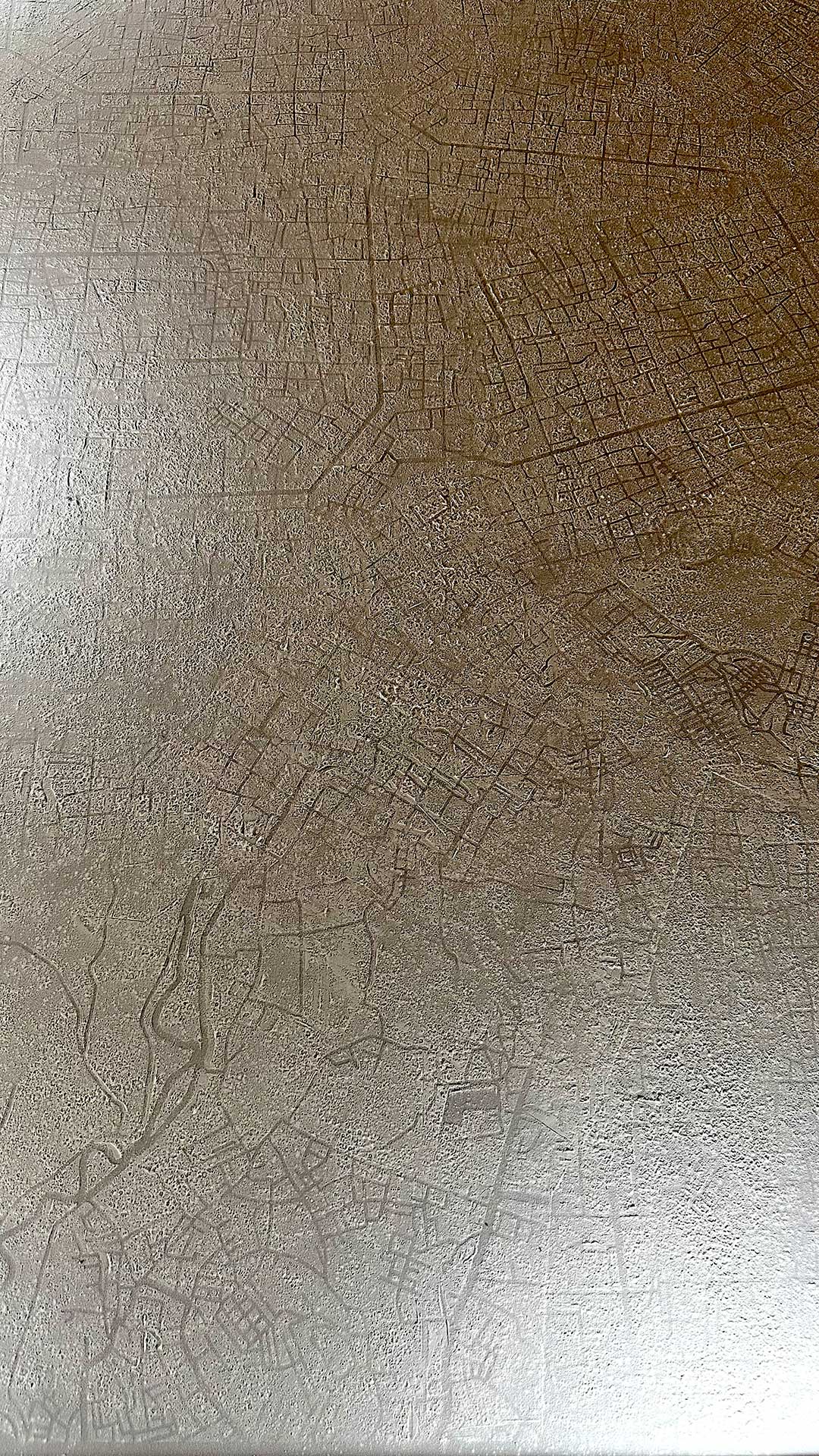

Nipan Oranniwesna’s artwork presented at the Chiang Rai Biennale under the theme Silence Traces is a fascinating example and provides the audiences with an opportunity to explore the power mechanisms and mapping technology of the Thai state. Nipan has used a variety of maps in the play as the main element and narrative of the exhibition. The first map was a military map of the border area of Chiang Rai. The oldest map was produced in 1936 and was used until 1967. This map was obtained in collaboration with the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture (OCAC) in requesting copies for display. The second map is a display of aerial photographs covering the entire Chiang Rai province and is publicly accessible and downloadable. The final map was an artistic installation in the middle of the hall. Nipan took maps of Chiang Rai’s five districts from a publicly accessible website and printed them out. He then cut out the remaining elements on the map, leaving only roads and rivers. The perforated panels became a template for artists to sprinkle powder on, to replace the blank areas that had been cut out, even as the powder clumps into a landscape on a canvas. Nipan’s work not only gives us a greater understanding of space and national borders, it also allows the human eye to layer perception onto military imaging technology. This experiment, seen through the lens of state security, provides a moment for viewers to reconsider the dimensions of the past from a present time and opens a moment for the viewer’s experience to entertain dialogue with the state narrative. Nipan does not leave traces on the surface of the artwork alone. His work creates mental traces as visual dialectics between personal memories, collective memory and memories created by the state.

3 Thanavi Chotpradit, “Of Art and absurdity: military, censorship, and contemporary art in Thailand,” Journal of Asia-Pacific pop culture Vol.3, No.1 (2018): 5-25.

4 Thanavi Chotpradit, “SHATTERING GLASS CEILING,” in The Routledge Companion to Art and Activism in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Lesley Shipley and Mey-Yen Moriuchi (eds Taylor & Francis: 2022).

5 Pandit Chanrochanakit, “Deforming Thai Politics: As read through Thai Contemporary Art,” Third Text Vol. 25. No. 4 (2011): 419-429.; Pandit Chanrochanakit, “Reluctant Avant-Garde: Politics and Art in Thailand” Obieg Magazine (2016).

If Nipan’s work is an attempt to demolish and question the space which was designed by the state, Pandit Chanrochanakit, the curator of Sla Khin Pavilion: Opening J. Prommin’s World has taken steps in the opposite direction. In particular, this involves the presentation of landscape paintings by Jamrus Prommin, a Chiang Rai artist who lived between 1934 and 1999. Jamrus was a painter who practiced his abilities and created unique works through industrial painting. On the surface, his work may not stand out or show a complex process, but if we look deeper, his paintings are like a record and exploration of the landscape of Chiang Rai province through the artistic process. Jamrus’s work is similar to pictorial ethnography, which aims to describe ordinary people’s lives in detail through the picture. The difference is that Jamrus is not an ethnographer who focuses on studying other societies. His art is documenting the stories of people in their homeland through travel and a trained eye, in order to tell stories that complement what aerial photographs and military maps cannot. Considering this aspect, the Sla Khin Pavilion: Opening J. Prommin’s World is extremely successful in letting the stories and perspectives of ordinary people about their homeland and territory come to life through a series of memories in the moment of viewing. In an academic way, we understand and accept that the sovereignty of the modern state that controls and orders people’s lives and the ideology of nationalism is mapped.6 However, Pandit’s curatorial work has the potential to cause viewers to question the Geo-body (Big – G) that was created through power innovations such as maps and military technology, then fills in the gaps created by the intersection of latitude and longitude. By featuring the views and perspectives of ordinary people, this installation leads us to imagine that with geo-body (little – g) the map is redrawn from people’s lived experiences.

Of course, Chiang Rai’s borders and areas of exploration for artists and curators are challenging. The border is also a space of life and disappearance. It has always been a field of power relations between the state and localities. The artwork titled The Actor from Golden Triangle by Taiwanese artist Hsu Chia–Wei explores and connects people’s experiences, historical dimensions of the area, and the Golden Triangle area brought together interestingly through a short documentary video inside a room covered in red film. The video Huai Mo Village features an interview with a man who has a troubled past as a CIA agent working in the Golden Triangle. This former spy was once captured and tortured by Khun Sa, an influential drug trafficker on the border. As an artist, Chia-Wei works with orphans and trains them in documentary filming skills. These orphans lost their parents through their involvement with drugs. They were later adopted by that man in the video. The story in the documentary is like the turbulent waves beneath the surface of the Mekong River, which flows smoothly and calmly. The room’s red atmosphere has become a reminder of the insecurity and state of exception of the Golden Triangle. In this borderland, Chia-Wei presents a story that is repressed and closed and can only exist in the in-between space that signifies towards the issue of public space through the artistic process. Therefore, his work is part of an attempting to tell the story of the forgotten group in modern state historiography.

What is the politics of hope? This question comes up often amid political turmoil in Thailand. Hope has always been a question of whether ordinary people can truly create hope. In a situation where activists and art activists are still being prosecuted and put into interrogation rooms the artworks displayed at the Chiang Rai Biennale are a testimony to the preservation of hope through the process of questioning and undermining the legitimacy that state power uses to control and dominate the people.

Art is a vital message of hope.

The artworks mentioned above are just some of the works exhibited in the Chiang Rai Biennale. Chiang Rai Biennale is a diverse collection of artists and creative processes, and it cannot be generally concluded that this is the best biennale in Thailand. However, from this visit, I have been reflecting and reconsidering continuously whether Chiang Rai Biennale differs greatly from the atmosphere of “Nationalistic Artistic Progress” in Thailand. Certainly, the crucial condition for this difference must lie in the political status of aesthetics, one which is not used to control or govern people anymore. I am reminded of the significant proposition of Jacques Rancière, a prominent French philosopher and theorist renowned for his contributions to aesthetics, politics, and critical theory.7 He has provided unique insights into the relationship between aesthetics and politics, challenging conventional notions of art and proposing a radical rethinking of the aesthetic experience. Rancière’s ideas on aesthetics can be described in the case in two key points. Firstly, he emphasizes the concept of “aesthetic equality,” suggesting that everyone has the capacity for aesthetic experience and the ability to participate in the realm of art. He rejects the traditional notion of aesthetics as an exclusive domain reserved for experts or a privileged elite. According to Rancière, aesthetic experiences are inherently democratic and can be accessed by anyone, irrespective of their social or cultural background. Secondly, he discusses “dissensus” and the “Politics of Aesthetics,” arguing that art possesses a political dimension and can challenge the existing order by disrupting established hierarchies and power structures.

The aesthetics experience of the Chiang Rai Biennial embraces new possibilities, with aesthetic equality at its core, allowing every viewer to access art in their own way and style. However, as an observer, I have noticed that attempts have been made to intervene in the process of art interpretation. Particularly twisting and adjusting the meaning of art to be consistent with Buddhist interpretations, including renowned monks from Chiang Rai province trying to incorporate art into the Buddhist worldview, or what can be termed “Buddhistization of the art.” They may believe that Buddhism represents Thai culture, and with the esteemed status of Buddhism, it can elevate and imbue artworks with greater value. Such perspectives pose a significant challenge to the awareness of equality and play a pivotal role in shaping the dynamics of power relations in aesthetics. Chiang Rai Biennial thus serves as an arena for the aesthetics of contestation, whereby groups endeavor to preserve the value of art, emphasizing the special status of artists and the varying significance of artworks. This event likewise incorporates the process of creating a liberation aesthetics and believing that everyone has the potential to access art equally.

7 Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible (New York/London: Continuum, 2004).

I remember an interview with Apichatpong Weerasethakul, a prominent film director and screenwriter, regarding the status of art in a context wherein AI is increasingly involved in the creative processes, thereby challenging the role of humans as creators. Apichatpong responded to the intriguing question by stating that for him, art is intellectual entertainment that helps broaden awareness and open discussions about the relationships between everything in the world, without necessarily adhering to the principle that art must be created solely by humans.8 The significance of this interview lies in considering art as intellectual entertainment, which seems to be a broad and inclusive response in various contexts. Certainly, promoting critical thinking and intellectual stimulation is crucial in the process of creating art. However, what deserves more scrutiny is how intellectual entertainment is incorporated into power structures and injustices in society through art exhibitions, events, and festivals. These activities occur under the auspices of the state in selecting and promoting artists and artworks so as to use their aesthetic work as a primary condition for perceiving the reality of the world and the positioning of individuals within the societal system. Apichatpong’s viewpoint thus seeks further explanation and caution in view of this interpretation. For me, the status of intellectual entertainment in art can be immensely valuable if it leads to a self-examined life journey in the realm of thought (vita contemplativa) moving towards the restoration of human conditions (vita activa). Contemporary art plays an increasingly vital role in liberating humanity from deeply ingrained beliefs. It also contributes to making the journey in the world of thought a part of creating change and destabilizing traditional thought structures.

Regarding intellectual entertainment, which is deemed important as mentioned, one cannot overlook or disregard the concept of equality in the aesthetics experience of art. Equality is a fundamental principle that enables everyone to access and enjoy art equally, regardless of social status, culture, or the background of any individual. This means that prioritizing equality in the experience of aesthetics is not just about the relationship between creators and audiences. It’s also about the fairness and freedom that everyone should have. This ideal ensures that everyone can access and engage with art equally, seeking knowledge and emotional connection. Creating inclusive environments and providing opportunities for everyone to participate in creating and experiencing art is crucial today’s society and living conditions. Therefore, when considering intellectual entertainment in this context, one must recognize the importance of equality in accessing and engaging with aesthetics without discrimination. It also involves creating opportunities for everyone to participate in perceiving and creating art equally.

I conclude this artistic chronicle within the workspace of the Faculty of Fine Arts, Chiang Mai University. In a few days from now, my dear colleague, my student, and I will have to face legal action for allegedly occupying the university’s art center in order to make it a public space where all types of art can be exhibited and utilized. In 2021-2022, many of our students had their artworks censored, preventing them from being displayed in the university’s art center. Some students faced legal action under Article 112 because their artistic activities were saying the unsayable in Thai society. But what is the power of art if it is not the voice of the voiceless? If it is not an attempt to change the structures of people’s perceptions and consciousness in society?

Visiting Chiang Rai Biennale made me realize the essence of making art democratic. I also drew inspiration from many artworks. Presenting the voices of ordinary people and the voiceless through artistic processes is crucial for promoting aesthetic equality. It is also essential for respecting diversity, respecting different opinions, and being aware of the right and freedom of expression. I immediately realized that amidst the government’s attempt to institutionalize art as its working tool, the artworks mentioned above have sharply criticized the state’s thought structures. It is time to develop a truly democratic Biennale that is free from state intervention. It is time for art festivals to be organized by the common people and for freedom to become an organic aesthetic that people have carried with them since birth, and always already understand as their natural right.

The battleground for aesthetic equality can and does exist anywhere and everywhere.

8 Pimchanok Puksuk, “A Conversation with Apichatpong,” 2024 at The 101 World 7 February, https://www.the101.world/a-conversation-with-apichatpong/?fbclid=IwAR2S4o9HpdTo_WA-LpegcB79YI5ckaF3aguVMbSBLIyYhYQPISf9SjnEr70

1 Thak Chaloemtiarana, Thailand: The Politics of despotic paternalism (SEAP Publicationl, 2007).

; Soren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager, “Saying the Unsayable: Monarchy and Democracy in Thailand,” in NIAS Studies in Asian Topics (NIAS Press, 2010); Nattapoll Chaiching, “The Monarchy and the Royalist Movement in Modern Thai Politics, 1932 – 1957,” in Saying the Unsayable: Monarchy and Democracy in Thailand, ed. Soren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager, (NIAS Studies in Asian Topics, NIAS Press,2010).

2 David Teh, Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary (The MIT Press:2017).; David Teh and other authors, Artist-to-Artist: Independent Art Festivals in Chiang Mai 1992–98 (Afterall Books in association with Asia Art Archive and the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College: 2018).; Thasnai Sethaseree “The Po-Mo Artistic Movement in Thailand: Overlapping Tactics and Practices,” Asian Culture and History Vol.3, No. 1: 31-45.

3 Thanavi Chotpradit, “Of Art and absurdity: military, censorship, and contemporary art in Thailand,” Journal of Asia-Pacific pop culture Vol.3, No.1 (2018): 5-25.

4 Thanavi Chotpradit, “SHATTERING GLASS CEILING,” in The Routledge Companion to Art and Activism in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Lesley Shipley and Mey-Yen Moriuchi (eds Taylor & Francis: 2022).

5 Pandit Chanrochanakit, “Deforming Thai Politics: As read through Thai Contemporary Art,” Third Text Vol. 25. No. 4 (2011): 419-429.; Pandit Chanrochanakit, “Reluctant Avant-Garde: Politics and Art in Thailand” Obieg Magazine (2016).

6 Winichakul, 1997

7 Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible (New York/London: Continuum, 2004).

8 Pimchanok Puksuk, “A Conversation with Apichatpong,” 2024 at The 101 World 7 February, https://www.the101.world/a-conversation-with-apichatpong/?fbclid=IwAR2S4o9HpdTo_WA-LpegcB79YI5ckaF3aguVMbSBLIyYhYQPISf9SjnEr70

Share

Author

Sorayut Aiem-UeaYut is a lecturer in Visual Culture and Design Culture at the Dept. of Media, Arts & Design at Chiang Mai University, and a doctoral candidate in Germany. His interests include anthropology of the arts, sensory politics, object-oriented ontology, and the technological turn. He received his B.A. and M.A. in Anthropology from Chiang Mai University and Thammasat University, with training as a photographer through his fieldwork among the people and objects in the deep south of Thailand and the Malay peninsula. His current research focuses on (in)visuality in Tamil immigrant laborers who live and work in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He is an ethnographic photography trainer for researchers at Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhon Anthropology Center.

Sponsor