In a departure from other international art exhibitions, the documenta fifteen that took place in 2022 in Kassel, Germany, stood out for the discursive depth and width with which it assimilated south-eastern Asian cultural idioms as one of its salient features. It also distinguished itself in organizing the multifarious projects, performances and activities in a resource-sharing, and collaborative spirit. This ambitious and ever-growing exhibition thus presented a challenge to researchers who endeavor to sketch a profile of the enormous scale and scope of its whole events and participatory projects. Other than having to delve into the complex cultural contexts of the diverse collectives, they are confronted with images, documentations and “fragmentary evidence” that “convey nothing of the affective dynamic that propels artists to make these projects and people to participate in them,” as cautioned by Claire Bishop on “researching art that engages with people and social processes.”2 Especially, researchers with limited resources are left to their own devices, sometimes with haphazard encounters as well as random interviews with savvy informants to resolve the obstacles at hand. In addition, the prevailing climate of critiquing individualism, the emphasis on horizontal organizations, and the anti-elitism tendency are liable to give rise to the cliché of binarism at the expense of pluralism. Taking into consideration all these challenges, researchers have to eventually tackle an even more intriguing conundrum: how to pose pertinent aesthetic questions, ones that are developed from the analysis of curatorial method, creative projects and social engagement, and ones that are free from the limit imposed by a field research based on fragmentary experiences?

Let’s take the “sustainability projects” in documenta 15 as an example. ruangrupa and Documenta gGmbH decide together that one euro from each ticket sold goes to the public tree planting at Reinhardswald in the State of Hessen, and to the Sustainable Village Project in Indonesia.3 Is this kind of support and cooperation an art practice or a praxis? Since viewers interested in the exhibition events are mostly informed of these projects from official press releases, they cannot but answer the question by looking into some sketchy information.

One thing is certain that through the press releases and some brief descriptions, it is rather difficult for viewers to grasp the real and complex relationships woven by music, rainforest, soil, oak trees, art works and various human and non-human actors of the project. However, the notion of “quality of the relationships,” proposed by Bishop in her critique of “relational aesthetics,”7 needs to be pointed out here as our central analysis approach to documenta 15. Because this notion indicates an entry into ruangrupa’s art practices that create its multiple linkages to other collectives, to viewers, to media, to cultural institutions, to government agencies, and also to the diverse ecosystems. It is precisely in these complex linkages and relationships that ruangrupa unfolds the aesthetic of its collective art projects. And by analyzing the aesthetic significance of relationship quality, researchers can further bring light to the political strength inherent to the artist collective as “Institution faible” (Weak Institution),8 and to their commoning force against the ecological and socio-economic crisis. Before we delve into our main topic, it is proper to trace the emanation of ruangrupa’s collective art practices.

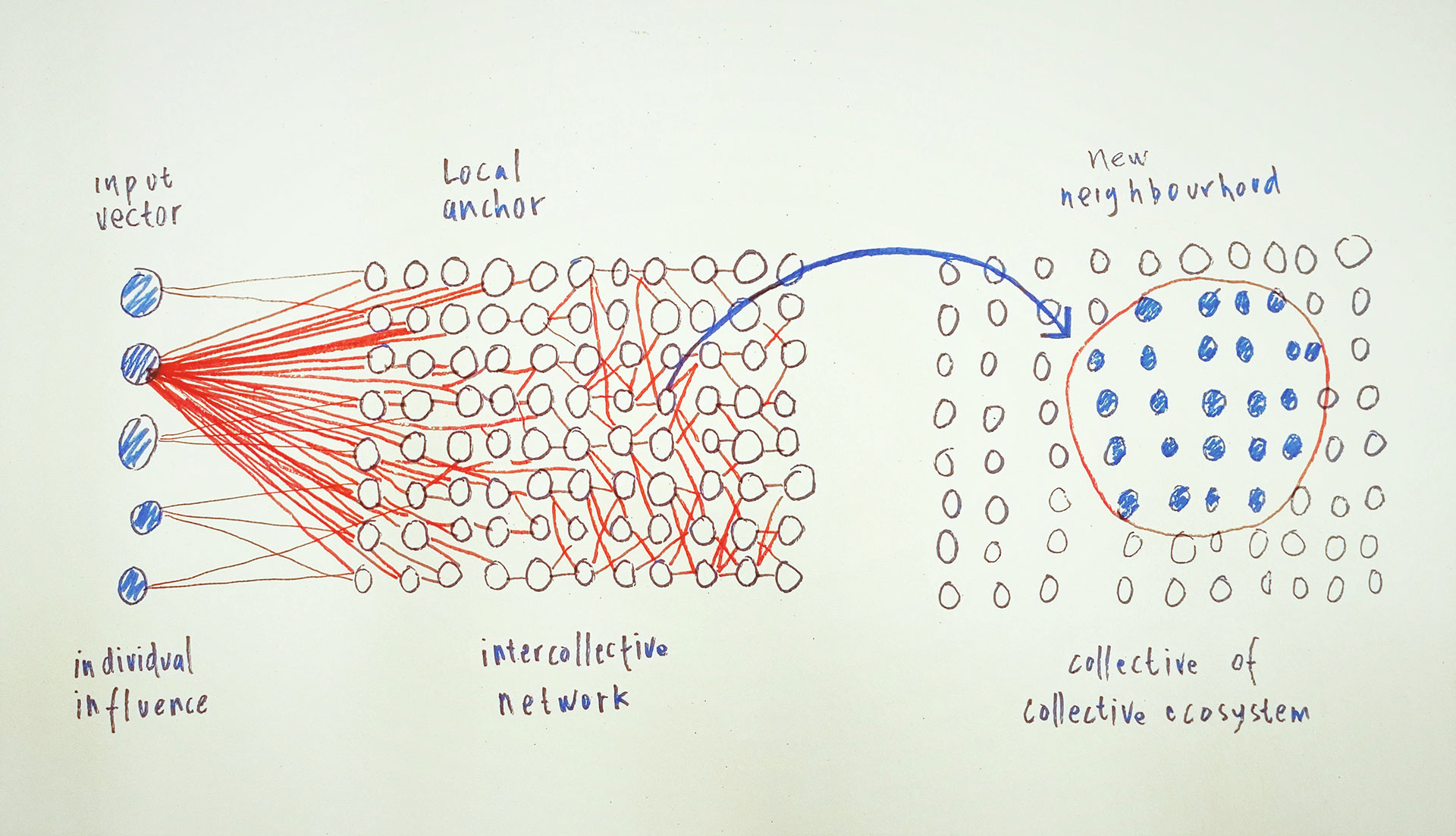

Central to documenta 15 is the networking surrounding “lumbung members” and “lumbung artists” that entwined “lumbung inter-lokal,” “lumbung Indonesia,” and “Kassel ekosistem.” Additionally, this lumbung network was extending to the participants from art market and to the independent publishers.9 Taking the resource institution as its axis, ruangrupa constituted the network of documenta 15 in the form of tree structure, from which the branches of collaborations radiate at each level. By unveiling the institutional linkages and the mechanism of collaboration, this networking endeavor of ruangrupa perfectly incorporates the mode of contemporary art production in the era of globalization.

Anne Cauquelin, the French philosopher, pointed out in 1992 that contemporary art has assimilated into the “communication regime.”10 According to her view, each participant of contemporary art is like a “node” in a communication network, capable of input, output; and is always regenerating and changing. In establishing the linkage between participants, the extensibility, multipolarity, and circularity of the network are put to full force.11 By extension, the more participant-nodes are interconnecting and the more dense, complex, and changeable the network becomes. Following Cauquelin’s argument, in contemporary art, the key of survival and the accumulation of capital depend on the interflow frequency among the participant-nodes and the intensity of the network connection.12 It is apparent that these characteristics of the contemporary art network are not only manifest in the lumbung curatorial project of documenta 15, but also in the development of ruangrupa’s collective art practices since the beginning of its inauguration in Indonesia.

The toppling of the Suharto regime is ensued by the Era of Reformasi, when the demands for freedom of association and speech, the liberation of living space, and the concerns for public affairs come into full swing in Indonesia. Against the backdrop of social transformation, came Ade Darmawan, who just returned from Rijksakademie, along with other five artists, founded ruangrupa in 2000 with the tenet of creating an international network for public discussion and free exchange of ideas.13 In the same year, ruangrupa joined RAIN (Rijksakademie Artist Initiative Network) which serves as a platform for connecting artist collectives from Latin America, Asia, and Africa in an alliance that explores non-Western approaches to arts and local knowledges.14 Since then, ruangrupa has been piling up its “nodes” and networking energy through the participation of international art festivals. The experiences from Gwangju Biennial in 2002 and Istanbul Biennial in 2005 pave the way for the international networking of ruangrupa which was fully revealed in its 10th anniversary event.15 After the success in Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in 2012 and São Paulo Art Biennial in 2014, this thriving group made its debut as a curatorial collective in Europe for SONSBEEK ’16 in Arnhem. It is important to point out that through several years of international network-building, ruangrupa has further demonstrated its flourishing achievement in establishing a more complex and more extensive collaboration platform for documenta 15. On the home front, ruangrupa along with other artists and collectives also took a decades-long effort to create local networks which continue to have a great impact in fostering the development of Indonesia’s artworld and culture.

In response to the rise of video images and underground culture on the internet, ruangrupa has since 2003 initiated the OK. VIDEO Indonesia International Media Art Festival designed to investigate the audiovisual language in relation to urban life and to examine the politics of images.16 After eight operations, the event was suspended in 2017, yet ruangrupa has made the video art a major medium of contemporary art in Indonesia in the 2000s.17 In addition, the way of merging public forums into collective art practice was introduced since 2004 in Jakarta 32°C, a biennial program that invites students to discover the social role of experimental art practices while bringing dynamics to art schools. The “nodes” constituting ruangrupa’s local network encompass not only the public, students, sponsors, and art institutions, but also artists and collectives from all over Indonesia. Especially, in 2010, Darmawan organized a group exhibition entitled “FIXER,” which connected seventeen alternative spaces together with artist collectives. Underlining the praxis of the local initiatives, FIXER incorporates a network of mutual support communities that helps artists weather survival crises by improving the local art infrastructure.18 Since then, it is apparent that ruangrupa’s networking endeavors were moving toward the direction of “collective of collectives.”19 Thus, in 2015, ruangrupa along with Grafis Huru Hara and Serrum jointly set up Gudang Sarinah Ekosistem as a collective art practice of socio-economic experiment, which, in turn, evolved into Gudskul in 2018 that merged the pedagogy into art practices.

If we examine the evolution of ruangrupa in the last twenty years through the prism of Cauquelin’s “communication regime,” it vividly reflects the globalized mode of contemporary art production and its prevailing networking vehicle of festivals, forums, exhibitions, screenings, and workshops. From ruangrupa’s point of view, the networking embodies the spirit of the times in the contemporary art history in Indonesia. It marks the transition of the artist collectives’ quest for freedom and independence to mutually supportive sustainability, as well as the shift from anti-totalitarian activism to interdependent collectivism.20 Therefore, Berto Tukan, a subject coordinator of Gudskul, identifies the contemporary art practices of an Indonesian art collective as a “social experiment of living together.”21 But after all, what kind of relationship quality does the solidarity, interdependence, and living together reveal in ruangrupa’s networking practices? In an interview in 2012, Darmawan mentioned that establishing a network is comparable to the idea of building an open, organic, and spontaneous friendship which also means a political act.22 Nevertheless, if we pursue the question further, what substantive change will be effected on the political strength and affective dynamic in friendship-building when the relationship quality in contemporary art network correlates closely with the frequency and intensity of connection between participant-nodes?

As Cauquelin emphasized, the contemporary art practices and works in the “communication regime” are no longer bonded with the aesthetic values and the substance of art itself.23 Consequently, the reality in which contemporary art is defined today pertains rather to the production and consumption of signs within the communication network, to the quantitative value system of bureaucracy, and to the intense personal connections. That is to say, the aesthetic values that artists once believed are already dissolved in networks and substituted for images and cultural signs for diffusing, tweeting and reposting. Even though Cauquelin unveils a cruel reality of the artworld today, it does not indicate that the friendship-building in collective art practice is just a way of aestheticizing the nepotism, and that the ideal of commoning cannot but reproduce the self-referential echo chambers. Otherwise, a slippery slope argument of this kind will pose a risk of flattening the aesthetic significations that ruangrupa unfolds in documenta 15. In order not to be overwhelmed by the tendency toward trivialization and commodification of the contemporary art network, researchers can further scrutinize the transmutation of friendship and commoning practices that actually took place in Kassel during one hundred days of the exhibition.

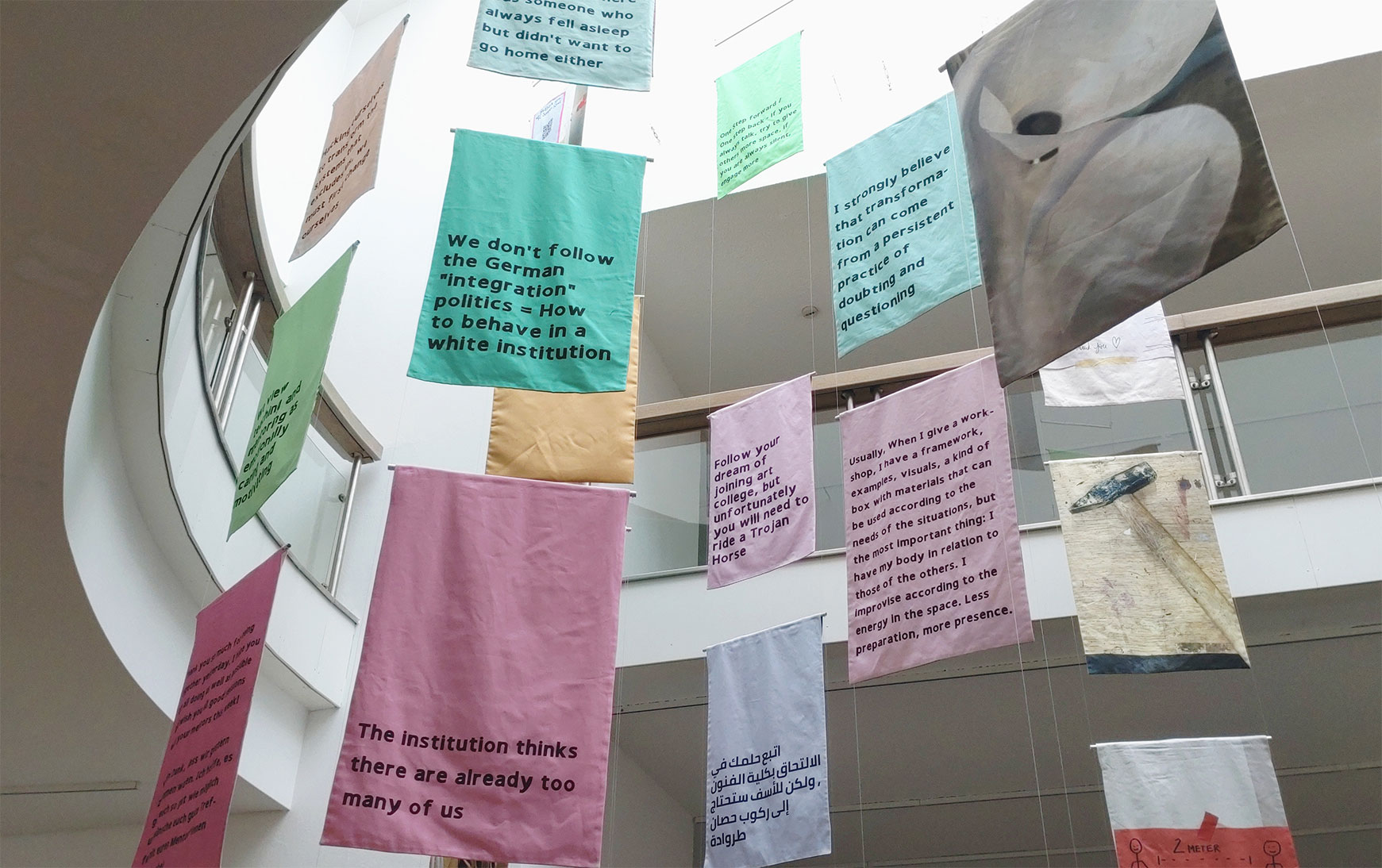

When visiting the Museum Fridericianum, viewers can hardly miss Dan Perjovschi’s drawing that dressed up the columns at the main entrance in lumbung values.24 Along with the Romanian artist’s live artwork, exuded some spectacular effect, the mind maps dotting the Fridskul walls and the colorful banners hung by the artist collective *foundationClass in the atrium of the museum. While inundated by these visual signs and hashtag-like slogans, casual visitors who roamed through the various venues may easily overlook Perjovschi’s contribution to local art network in Romania25, or fail to grasp the collaboration energy generated by *foundationClass with the migrant communities, and the dynamic of collective knowledge-sharing wrought by Fridskul. Ideally, the aesthetic value of these art practices is supposed to manifest itself in the exhibition. Instead, the quality of the relationships and interconnections varies as it spreads out from axis to branches according to the tree structure formed by the resource distribution frame of documenta 15. Thus, the lumbung artists with whom Perjovschi frequently communicated in mini-majelises were able to develop together a close resource-sharing linkage and an intense collaboration energy. Through this kind of strong networking mechanism designed by ruangrupa, the lumbung artists and lumbung members, as central participant-nodes, created solid connections and friendships in mutually reinforcing intensity, namely, a vigorous and rich quality of relationships. By contrast, general viewers, as outer participant-nodes, may participate Gudskul’s workshops or may ultimately have the chance to chat with the artists or share a bite with them in the gudkitchen; they may also attend CAMP’s talks on commoning art practices, then spend night in a DJ party at the site of Hafenstrsße 76. Artists, viewers, curators and all the lumbung participants likely mingle together in the joyful convivial atmosphere and hedonic mist of contemporary art, while the potential strength of commoning and the intensity of friendship-building are evaporated in the experience economy embedded in the prominent international exhibition.

4 Before the reforesting action on the International Day of Forests, Reza and Iswanto Hartono from ruangrupa, together with Sabine Schormann, managing director of Documenta and Museum Fridericianum gGmbH, Michael Gerst, director of the state agency HessenForst and Markus Ziegeler, Head of Forestry Office Reinhardshagen, have planted an avenue of oak trees representing 22 hectares of damaged forest in Reinhardswald on November 26 2021. HessenForst, “Documenta Fifteen Unterstützt Wiederbewaldung im Forstamt Reinhardshagen. Weitere Pflanzaktionen Sollen Folgen,” HessenForst, 2021/11/29. https://www.hessen-forst.net/post/aktuelles/eichen-fuer-den-reinhardswald (Accessed 2023/01/02).

6 Observing the biodiversity of tropical lowland rainforests in Sumatra for a long time, these 160 researchers from different universities in Germany and Indonesia have formed a research centre EFForTS and have already carried out research projects in 2012. In addition, in collaboration with documenta 15, EFForTS organized an exhibition of science and art in Forum Wissen in the University of Göttingen for the research results of the Sustainable Village Project. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, ”Research and Art Connect for Sustainability – a Cooperation Between the CRC 990 and the University of Göttingen with documenta fifteen,” Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, 2022. https://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/658092.html (Accessed 2023/01/02).

Since early 2019, when ruangrupa was appointed as the artistic direction of documenta 15, until the present day after its closure, the repercussions of the lumbung networking and commoning practices spreading from Kassel and Indonesia, are still felt today worldwide. In three years of curatorial marathon, ruangrupa endeavors to persevere with the ideal of sustainability and reinvention of the institutional network of artworld, but not without making some compromises while relying on the art exhibition system. Ruangrupa admitted in the documenta 15 handbook that it is difficult to be free from the various shackles of a conventional artistic mega-event26. The curatorial team was compelled to stick to the limited time frame imposed by the budgetary constraint, to deal with the rigid bureaucracy, to operate under a stifling hierarchical system, and not to mention the underlying “communication regime” of contemporary art. As a result, ruangrupa was unable to achieve the goal of its decentralization project by simply extending the axis of venues toward the East Kassel. Moreover, the quality of the relationships that defines the aesthetic values of lumbung practices is bound to be transmuted both within the tree structure of documenta 15 and in the international contemporary art network. Therefore, it is more amenable for ruangrupa, with the artistic team, lumbung artists and lumbung members, to develop a close-knit “collective of collectives” as a network of the commons, on the one hand. On the other hand, mostly perceiving the fleeting and fragmentary relationship quality produced by the commodified art experiences and the bureaucracy system, viewers or participants on the fringes of the lumbung network, including Documenta administration staff, are unlikely prepared to engage in the commoning practices of reinventing the institutional network of contemporary art. However, it is noteworthy that by closely collaborating with neighborhood communities and artist collectives in the city, the Kassel ekosistem unfolded from ruruHaus, and Markus Ambach’s collective art project Eine Landschaft both managed to dismantle the division between periphery and center. Especially, with the aim of regenerating the urban landscape and local culture in a collective endeavor, these initiatives were able to further consolidate the solidarity action network and friendships between communities anchored in Kassel.27

Other than the conundrum of networking structure featured in the mega art event itself, a series of allegations and controversies of antisemitism which burdened documenta 15 raises also the question about relationship quality that ruangrupa cultivated with the cultural and socio-political institutions in Germany. In particular, when the large banner People’s Justice by the Indonesian art collective Taring Padi was displayed at Friedrichsplatz a day before the opening, the turmoil ignited by the antisemitic figures harshly challenged the friendship-building and the lumbung values of documenta 15. Undermining the aesthetic import of artworks and exhibition, the proliferation of decontextualized visual signs and populist expressions on news, social media and in the artworld revealed again the typical symptom of contemporary art production in the “communication regime.” But most importantly, the means by which the curatorial team, artists and Documenta gGmbH tackled the controversies further bring up other questions – how does a contemporary artist or a collective negotiate their way out of the “institutional complex” which stems from the historical and socio-political entanglements of contemporary art networking? What quality of the relationships can a collective art practice produce between different institutions? Above all, how does an artist collective unfold the aesthetic and politics of commoning within an institutional network that entwines contemporary art with society?

So as not to pass over artist’s potential strength of reconstituting the institutional network of a society, it is essential here to steer clear of historical avant-garde’s traditional discourse in which compliant and conservative tendency of institution is hastily pitted against the spirit of freedom and resistance of artist. If, as Darmawan remarked, the artist has become a “mediator” in a divided and polarized society28, she or he is meant to reflect on the diverse strategies of collaborating with the institutions, thus to create a more heterogeneous quality of relationships and a more multifarious institutional network.

27 Markus Ambach was one of the artists invited by lumbung member ZK/U – Center for Art and Urbanistics. By connecting the protagonists living in around 11 locations in East Kassel, his project Eine Landschaft aimed to create a local knowledge network against the universality of global market. During the documenta 15, the artist also organized an urban trail according to which the viewers were invited to visit these protagonists and to communicate with them. On the one hand, this project revealed a clear contrast between the local knowledge growing from the right bank of Fulda River and the international discourse characterized by Documenta on the left bank. On the other hand, the commoning praxis and the close connections of these local protagonists form a social and ecological resources network which has functioned outside the Documenta over a period of time. For example, the self-organized organic food store MILA, the community garden Blüchergarten, and the laboratory of the urban agriculture SOLAWI Gärtnerei Fuldaaue have created together on the Fulda’s floodplain a system of the community circular economy based on ecological farming, sustainable consumption and mutual aid support, which differs a lot from the mode of production of Documenta. As a result, through the existing network embedded in East Kassel, Ambach’s project was able to break away from the tree structure of documenta 15 while highlighting the quality of the social and ecological relationships of local communities. However, did the research activities and all the participatory programs undertaken in this project make the friendships between communities more consistent and dynamic? And by collaborating with architect Renée Tribble, will Ambach be able to develop with the inhabitants and the protagonists of East Kassel a political strength to transform the urban environment? It seems that it still takes time for the project Eine Landschaft to fully unfold the aesthetic of its collective art practices. EINE LANDSCHAFT, 2022. https://eine-landschaft.de (Accessed 2023/01/13). Regarding the network of Kassel ekosistem organized by ruangrupa from ruruHaus, see: documenta fifteen,“ Local Cooperations in Kassel – the Program of Kassel’s Ekosistem at Ruruhaus,” Documenta Fifteen, 2022.08.30. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/press-releases/local-cooperations-in-kassel-the-program-of-kassels-ekosistem-at-ruruhaus (Accessed 2023/01/13).

By referring to Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe’s political philosophy, Bishop stresses that “antagonism” is an essential element in democratic society and in relationships constituted by art practices.29 Following Bishop, she points out that the relation of conflict is not only the condition for the existence of a pluralist politic of democracy, but also the limit of its full completion as a heterogeneous community.30 However, instead of enclosing herself within antagonism, Bishop further underlines the tensions and contradictions inherent to the constitution of a heterogeneous social relationship where the multitudinous subject constantly takes place. Accordingly, as mediators aiming at organizing the resistance network of oppressed dissidents, artists are able to “sustain” the inherent tension of the commons.31 Also, Farid Rakun, in talking about the anti-establishment approach of ruangrupa, reminds us that rather than getting stranded in antagonism, only by creating something differently while criticizing can we open up for changes in difficult situations.32 By undertaking a networking strategy that is both hostile and friendly, critical and collaborative, the artist collectives in Indonesia today thus maintain the tension in the complex relationships with government, art institutions, funding agencies, and the public, to such extent that the collaboration platforms have the potential to constitute a pluralist ecosystem and a network of commoning. Therefore, sustaining the tension inherent to the heterogeneous commons does not mean to simply persist in a hostile relationship and social conflict. The art of sustaining the tension rather calls for the constant reinvention of subjectivity and the regeneration of diverse relationships in a confrontational and disruptive situation, in order to avert the political strength of the commons from dissolving in the deadlock of binary opposition and the tragedy of mutual destruction. From this point of view, sustaining the inherent tension of the commons is ipso facto to maintain the creative tension within friendship, namely, a relationship developed both by criticism and creation, and by confrontation and care. For this reason, in the face of the antisemitism controversies, it was crucial for lumbung actors and participants to keep the creative tension unfolding among friends for consolidating not only the relationship between artists and institutions, but also the political strength of collective art practices.

In the course of the whole curatorial project of documenta 15, ruangrupa incessantly underlined the practice of “lumbung.” In the traditional society of Indonesia, “lumbung” designates a resource-sharing barn for grain storage; it additionally serves as a gathering place for community bonding, local knowledge transmission, as well as ethical and ecological relationships building.33 In other words, “lumbung” represents a commoning platform where people sustain the tension of a complex relationship and cultivate its quality in constant negotiating, collaborating, and creating the multiple linkages with each other and environment. However, the commons constituted within “lumbung” are subjects to change under different social milieus and scenarios that entails differing negotiating strategies and commoning approaches to maintain its inherent tension for regeneration. Accordingly, the antisemitism allegations that haunted documenta 15 and the extended antagonistic discourses surrounding the controversies made it abundantly clear that to transplant the Indonesian lumbung to German soil needed more time to weave the local network connections and to develop a collective art practice which could sustain the creative tension of the commons.

This is not to downplay the vigorous defense of ruangrupa and all the lumbung participants for diversity, equality and freedom of expression after a series of racist attacks, questionings, and including the censorings by the Supervisory Board of Documenta gGmbH. Doubtless, their statements, petitions, and some protests by withdrawing from the quinquennial exhibition were all necessary and important for the struggle. Nevertheless, while confronting the conservative art institutions, populist media hype and the reactionary politics in Germany, should the political strength and the tension of the commons revealed in lumbung’s collective art practices be unilaterally crushed by the punch of disciplinary measures and the wave of hatred? If the primordial focus of ruangrupa for documenta 15 is on addressing socio-political and historical trauma from various perspectives – thus, on sustaining the creative tension of the commons,34 can lumbung commoning practices open up an alternative way to tackle the “institutional complex” which emerged from the Germany history and society?

After going through all the adventures and challenges that have appeared in documenta 15, ruangrupa’s collective art practice has shown us how the relationship quality of the commons varies within the contemporary art network. It is then the commoning practices of the art collectives in Indonesia and the “boomerang effect” of the antisemitism controversies that underline the importance of maintaining the creative tension of the commons. Moreover, the collective art practice that keeps the commons and the politics of friendship flourishing in the creative tension provides in fact a profound sense of sustainability advocated by ruangrupa. Sustainability does not just consist in constituting a livable and heterogeneous ecosystem in economic and ecological terms; it also indicates the idea of conceiving diverse approaches of commoning that could persistently create a dynamic relationship quality in aesthetic terms. Analyzing the aesthetic of ruangrupa’s commoning and networking practices from this perspective, its various possible development paths thus come into view: how will the lumbung network continue to develop and expand? Will ruangrupa persevere in constituting a more localized and sustainable network of contemporary art in Kassel even in Europe? Or, instead, will the “inter-collective expansion” of ruangrupa, as Iswanto put it, push itself towards a further self-dissolution?38 Undoubtedly, to answer these questions, it is essential to keep delving into the multiple significances of sustainability and the “aesth-ethic” import of ruangrupa’s projects carried out in the future.

35 Eyal Weizman, “In Kassel,” London Review of Books, vol. 44, no. 15, 2022. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v44/n15/eyal-weizman/in-kassel (Accessed 2023/01/16). Darmawan also pointed out: “The image is of European origin, then transformed and appropriated within our own cultural context in an unacceptable way.” See : documenta fifteen,“ Speech by Ade Darmawan (Ruangrupa) in The Committee on Culture and Media, German Bundestag, July 6, 2022,” Documenta Fifteen, 2022.07.09. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/news/speech-by-ade-darmawan-ruangrupa-in-the-committee-on-culture-and-media-german-bundestag-july-6-2022 (Accessed 2023/01/16).

37 documenta fifteen,“Ruangrupa and the Artistic Team on Dismantling ‘People Justice,’” documenta fifteen, 2022.06.23. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/news/ruangrupa-on-dismantling-peoples-justice-by-taring-padi (Accessed 2023/01/16)

4 Before the reforesting action on the International Day of Forests, Reza and Iswanto Hartono from ruangrupa, together with Sabine Schormann, managing director of Documenta and Museum Fridericianum gGmbH, Michael Gerst, director of the state agency HessenForst and Markus Ziegeler, Head of Forestry Office Reinhardshagen, have planted an avenue of oak trees representing 22 hectares of damaged forest in Reinhardswald on November 26 2021. HessenForst, “Documenta Fifteen Unterstützt Wiederbewaldung im Forstamt Reinhardshagen. Weitere Pflanzaktionen Sollen Folgen,” HessenForst, 2021/11/29. https://www.hessen-forst.net/post/aktuelles/eichen-fuer-den-reinhardswald (Accessed 2023/01/02).

Share

Author

Author