In our digitally network societies, one can gather, organize, edit, and disseminate all kinds of information much more easily and quickly than ever before. This capacity overlaps with contemporary modes of searching, thinking, and acting so as to evoke scenarios of knowing and learning. This in turn makes more cultural workers, including scholars and researchers, pay attention to and/or engage in curatorial activities—or causes curators to follow paths of theoretical thinking developed parallel to academic discourses.1 Through contemplating the changes in knowledge landscapes brought about by current technologies, this text reflects on curatorial practices and their meaning and agency in the age of digital culture; moreover, it posits a position, the curatorial as a praxis2 of disobedience.

Introduction

In his introduction to Growing Explanations, M. Norton Wise, a historian of science, refers to the fascination with complexity that has emerged in societies since the Second World War. He goes on to explain that this fascination is closely linked to the conceptualization of the computer and its development as a device central to processing, distributing, and mapping large amounts of information. While such decisions have opened up various mathematical techniques for generating information in processes of modeling, simulation, morphological analysis, et cetera, they have also given rise to data-driven thinking in the process of investigating and understanding, and have settled deep within everyday life with their symbolism. Exemplified in practices of clicking on “friending,” “like,” “linking,” “going,” et cetera, our attitudes, emotions and attention are transformed into numbers, and the adherent symbolism endlessly proliferates symbolic desire. No matter how deeply and even immanently the architecture of algorithms embraces the complexities, the fundamental principle of segmentation in digital aesthetics seemingly penetrates through to form the outcomes, and thus underscores the tendency towards views that polarize rather than connect. This mirrors a “direction of thinking” that is inscribed in the aesthetics of digital culture and its organization—the mathematization of life.

1 There are many examples of academic scholars’ involvement in curatorial projects. One early example is Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s work with Alfredo Jaar (One or Two Things I Imagine About Them, 1992), while another prominent scholar would be Bruno Latour, who has been involved in several large curatorial projects, including Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art (with Peter Weibel) of 2002, Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy of 2005, and Reset Modernity! of 2016, and is a co-curator of the forthcoming Taipei Biennale in 2020, and more recently also Chris Kraus’s Films Before and After of 2019, and many others.

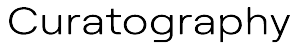

Satoko Nema, Paradigm (installation view), Heidelberger Kunstverein, 2018, photo © Satoko Nema

Lively discussions of technologies and their governance and effects (or affects) on life in organology are currently taking place. The arguments stem from a tendency to regard technology as the dominant agent in contemporary life. Whether one agrees with this idea or not, a counter-question arises: Do we always need to think of life through the lens of technology in order to enable to follow its direction of thinking? Thinking about aesthetics in such a way—situating technology at the center of world- and work-making—may give technology too much credit and simultaneously limits the potential of a multiplicity of perspectives to enrich our life. But how can we construct our relation to technology in other ways? What might be another direction of thinking be?

The French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy responded to the question, “Where is our future (after Fukushima)?” which was posed by the Japanese philosopher Osamu Nishitani in his eponymous text. In it, Nancy places emphasis on the thinking of totality and postulates new, different ways of imagining the future, other than knowing “more” and doing “better”: by this, he means that instead of orienting our imagination based on calculation and following a line of thinking so as to improve, control, conquer, or even overcome nature or the unknown, we need to find and propagate other approaches to imagining (Nancy, 2015). He continues on to say that “the world is not an object to observe, but . . . what we are and what we are making together” (Nancy, 2015).

While computation adopts a methodology of mathematical segmentation, the curatorial uses another methodology for handling complexity by means of connecting and gathering. Curators select, collect, move, present, and write about the exhibits. In globalized exhibition-making, curatorial activity makes it possible to experiment with different processes and orders of thinking in order to liberate processes of thinking from their modernistic values and systems, discourses, and categories. In other words, it events and invents knowledge within an epistemic structure and facilitates questioning the world from a 360-degree perspective. Starting from the assumption that curatorial activity is a space for producing different directions of thinking, this text discusses three artworks in Sharing as Caring no. 6, one of my curatorial projects, and orients our imagination towards an approach that differs from the algorithmic mode of thinking in order to consider other ways for us to address current technological situations.

The ongoing exhibition and event series Sharing as Caring was launched at the Heidelberger Kunstverein in 20123 and was planned to continue in yearly installments. It aimed and aims at providing opportunities to confront and reflect on the changing realities and cultural coordinates that have been developing since the devastation that hit the coastal region of Fukushima in March 2011. The series does not limit its scope to this nuclear catastrophe, since it regards the incident as merely one aspect of a more fundamental problem in the intricate structure of contemporary societies. Instead, the project encompasses a relationship between art, life and technology. Sharing as Caring no. 6 (November 31, 2018–February 4, 2019) was subtitled trans-Affects: Stories, Life and Landscapes, and presented three art works: Paradigm (2016) by Satoko Nema, Landscape Series no. 1 (2013) by Nguyen Trinh Thi, and Into Eternity (2011) by Michael Madsen. It addressed the notion of “caring” with respect to its intimate linking of political, economic, and psychological landscapes and of personal desires to technology. In what follows, I shall revisit these artworks and speculatively propose several meanings of the notion of “blur(ring),” whose significance for curatorial practice I have recently come to recognize.

2 Praxis in philosophy is not limited in meaning to just an action or activity. It is an action emancipated from teleological thinking and transformed to be the beginning. The use of praxis in this text is based on a further understanding Nancy’s use of the term. He understands praxis as a sensible action of openness and directed towards the sense of the world. He centers praxis as a means to encounter the world with sense and sensibility, to interact and act upon the world, and to expose ourselves to being altered by the world. He regards praxis as holding a potential to understand ethics and philosophy in openness and as a decision for existence characterized by the experience of freedom (of being at the beginning). By adopting his definition of praxis in the curatorial context, I attempt to suggest that curatorial practice not only embraces sensibility and the sense of the world in the sensual, but is also a decision and a determinate mode of being.

3 For details about the project, Sharing as Caring nos. 1–5 see “Glimpse over Five Years” in the newspaper Sharing as Caring. http://miyayoshida.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/HDKV_SAC-Zeitung_Screen.pdf.

Satoko Nema, Paradigm (installation view/detail), Heidelberger Kunstverein, 2018, photo © Satoko Nema

Blurring as a strategy against normalization

Paradigm (2016) by Satoko Nema is a series of photographs that consists of urban and natural landscapes on the island of Okinawa, the southern part of Japan. Each time she presents this work, Nema selects a new constellation of photographs from a total of fifty-two images, prints them in three sizes, and rearranges them in a new layout. At the Heidelberger Kunstverein, fifteen images were chosen and installed site-specifically: two enlarged digital prints on photographic paper installed directly on the dark blue wall (1800 × 2860 mm), eight photographs on acrylic panels in three different sizes installed around the large images (333 × 500 mm, 267 × 400 mm, 154 × 230 mm); one hanging on each side and six underneath, standing on the floor and leaning casually against the wall. In addition, three small works on acrylic panels were installed on the continuous walls in the exhibition space, and thus expanded the rhythm spatially and intensified the works’ relation to the exhibition space.

It does not take long to realize that Paradigm is all about life—the life of the artist. The constellation of photographs depicts a group of birds flying across the sky, an airplane high up in the sky, half hidden in the grey clouds, a dark forest at dawn, vital green plants on the street, electric cables hanging down in the city, and other motifs. They show what the artist encounters when she wakes up, steps out of her home, travels back and forth to work, or in the tranquility around midnight. None of the images are exotic, shocking, or speculative in their presentation of the tropical nature, political conflicts, and history of tolerance in Okinawa. They instead look quite mundane, despite the fact that many images, including the two large prints out, are extremely blurred: the forest melting down into the darkness, trees wildly oscillating, a shaky street view from a car window, a building tilting to the point of disappearing into the overexposed whitish background, lights jumping up and down like sound waves, and the moon dancing irregularly and elegantly in the dark as if celebrating its freedom from the gravity of its orbit around the Earth. The blurring calls to mind the brushstrokes in paintings by Gerhard Richter, who uses the technique to indicate memory and times past. At the same time, Nema’s images in Paradigm transport both the intimacy (presence) of painting and the distance (past) of photography in a peculiar way. With reference to the series of images, the artist says,

For example, this place is not standing still. The Earth revolves both on its own axis and around the sun at a very high speed. But we imagine we are not moving. I intended to overturn this perception. In reality our vision is blurred, but our brain compensates for this blurriness. My photos correct the images made by the brain. (S. Nema)4

The artist explains the blur as her artistic interpretation of physics and human cognition and her action as a response to our cognitive habits. This artistic observation could also apply to our cognitive acceptance of the technologies that filter and manipulate visual data by means of computer programs. Since the invention of photography, in 1826, the technology of photography has enabled us to see what we previously could not see. Along with mechanical and technological developments, including miniaturization, digitalization, and the integration of computers, interfaces, and software, we have come to take, see, and share images via mobile phones, iPads, digital cameras, or computers. However, these images are manipulated to alter lighting conditions, focal points, color balances, sharpness, et cetera, mostly in order to make images look “likable.” Our visual senses are constantly attuned to these “likable” aesthetics, and tend to accept them, or even to desire this look. Our perceptions are constantly being adjusted and reshaped to fit the parameters set by the algorithmic.

Resisting such technological penetration, when taking photos the artist moves her camera around with her body, instead of holding it still. The blur results from the process and thus rejects the order stipulated by the device and disrupts the calculation by its algorithms. It is the consequence of perceiving the world in line with the bodily event, without giving epistemological priority to the visual. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, the relationship between the body and electronic technology was extensively theorized by the field of so-called Media Art. Around the millennium, the embodied experience of technology reached another techno-sensual level—a new sensorium, which has developed further into organology, which thus blurs the boundaries between organism and machine. The aesthetics centered around technology enhance in order to dramatize the body by multiplying, mixing, and accelerating, or the hybrid sensory modality in both directions, towards the inside and the outside. In her body of work Eyesight Alone of more than a decade ago, Caroline A. Jones, an American art historian, examines the penetration of modernistic senses in paintings from the classical period to American Abstractionism, and points to the internalization of the visual priority and the disembodiment of acts of looking. She developed a thesis that the “bureaucratization of the senses” was systematized as a result of an unbalanced overall development focusing on the visual (Jones, 2005). Taking a direction opposite to sensationalism and the bureaucratization of the senses, Paradigm events the body to suggest another aesthetic possibility that may be sensible in blurring, a possibility that indicates directions of thinking that differ from the logic of “more” and “better.”

4 Satoko Nema in conversation with Miya Yoshida at the Heidelberger Kunstverein on December 1, 2018.

The blurring applied in Paradigm is also a bodily reflection of the history posited by the artist. She says: “It is important to accept the movement in the range of my arms and let them swing freely. It allows and embraces something unexpected or new to come in, therefore enables one to continue.”5 To rephrase: Movements on a bodily scale help us to continue questioning, reflecting, adjusting, and to sustain criticality towards everyday life, instead of simply surrendering ourselves to it. For the artist, who was born and is based in Okinawa, one of the most politically charged islands in the middle of the East China Sea, blurring is her visual language as well as her strategy of continuously resisting the forces and pressures of political powers—for resisting the government’s attempts to repress, fix, and frame any non/organic entities in the hierarchy. This resistant spirit, with all its inherent idiosyncrasies, can be adapted to address any enforced states of affairs. In a sense, blurring dis-occupies the occupied space. It capacitates the time-space to remain open so that it stays sensuous and sensible for the future. Thereby, blurring is not only a critique of digital aesthetics and our habitual acceptance, but also a political strategy for ongoing resistance to the normalization of power.

5 Ibid.

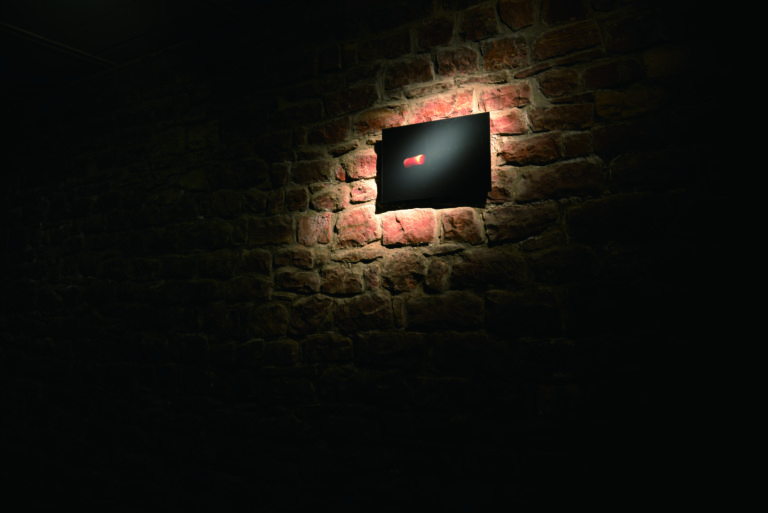

Blurring action, gestures of knowing

In her 35-mm slide installation, Landscape Series no. 1 (2013), Nguyen Trinh Thi, a Hanoi-based independent filmmaker and video/media artist, casually presents a collection of seventy-seven photographs. Each slide is projected on a rather small screen hanging freely from the ceiling. The series of images appears out of the darkness of the exhibition space. It clearly shows the Asian wo/men pointing to something in a landscape somewhere in the Asian countryside. The same images are printed in black and white on postcards of brownish recycling paper that lie randomly on a small desk next to the projection. The short description on the cards only says the names of various locations in Vietnam and neighboring countries. For viewers, it is unclear what exactly they indicate, or when, why and in which context these photos were taken.6 This unclearness leaves viewers in a limbo of puzzles and frustrations due to the lack of information, while the mechanical sound of a slide projector echoes loudly in a regular rhythm in the exhibition space and produces a retro-atmosphere that recalls the industrial age.

In fact, all these images were found on the Internet and collected by the artist. It might be possible to say that even the artist may not really know the true stories or accurate information connected with the images. At the same time, one must notice that the point of work does not lie in the artist or curator providing such information, but rather in the “gesture”— the gesture of pointing outward. Here, the lack of literal information—emptiness—functions as a window that guides one’s thinking. This gesture by the artist refuses to provide us with related information. In a study of the data-oriented society that stems from the development of cybernetics, Orit Halpern, an American cybernetic researcher and media theorist, introduced the term, “communicative objectivity” to depict the attitude shift that results from recording and displaying information by means of technologies, new forms of observations, rationality, and the resulting sets of actions based on economic management and analysis (Halpern, 2015). Landscape Series no. 1 utilizes the example of “communicative objectivity” so as to claim that, in the culture of symbolism, the process of knowing has become just like business management. The rational contingency of the gesture in the images reveals the logic of metadata, which navigates and frames the empty content in the “free” association with the gesture. Much in the same way as search engines, the work takes a gesture as a fact, as a trace of data in symbolic thinking, and playfully abuses such an approach so as to construct pseudo-evidence in her artwork. By displacing the symbolic mode of knowing in rural Asian landscapes, Thi has invented an image of “gesture” as a conceptual device for gesturing information. Through taking a gesture as more than “gesture,” the work performs a gesture of knowing.

By demanding viewers to engage in reconnecting her or his knowledge—from economies, politics, and societies to histories—Landscapes Series no. 1 shifts the act of knowing from the status of symbolic gesture to the sensitive imagination. Thi’s straightforward approach thus blurs the boundary between actions and gestures of knowing and calls our attention to current systems of searching and knowing as well as to the digital symbolism behind them.

6 Here, I chose the word “scale” instead of “level,” since the latter connotes hierarchy, but the former does not. I use the notion in reference to Le Corbusier, who used the human body to change the idea of space in modern architecture. Although I do not adhere to his idea of the human body as a unit in modernistic sense, I would like to refer to it as a method so as to formulate conceptual thoughts.

7 The artist gives a small hint about the work on her website. She introduces the anecdote of having made this work while thinking about the Fukushima catastrophe and pondering the Vietnamese government’s decision to build the first nuclear power plant in the Ninh Thuan Province in the southern part of the country, in collaboration with the Russian State company Atomstroyexport. In November 2016, the Vietnamese National Assembly abandoned its plans for this first nuclear power plant.

Left: Nguyen Trinh Thi, Landscape Series no.1, 2013, Right: Michael Madsen, Into Eternity, 2010, photo ©Marc Doradzillo

Blurring the sense of time

Into Eternity (2010) is a documentary film by Michael Madsen, an artist and a filmmaker based in Copenhagen, Denmark. The film starts with a silent snowscape deep in the natural landscape of Finland, which contrasts with the darkness of the space underground, where the sound of dynamites explosions and rock breakers echoes and vibrates in the air. The film deals with the construction of the Onkalo nuclear waste repository, which is designed at a location 4.5 km underground to store high-level radioactive waste produced in the country for a period of 100,000 years. No structure made by human beings has ever endured for such a long time. The construction site deep underground contrasts with the super clean rooms filled with high-tech control machines on the ground level. The underground site is a rough environment, where the power of nature overwhelms the human. The film introduces people who work for the plant, supplemented with interviews with a theologian, radiologists, physicists, and managers of Onkalo Co. Ltd., and confronts them the contradictions inherent to their ethical assessments of nuclear energy and their approach to handling the waste. Nothing dramatic happens, but the close observation of this ridiculous project evokes an affectivity beyond reason. The camera captures the silent hesitation of the scientists when asked questions. At such moments, sincerity as well as the mixed emotions of those being interviewed appear and highlight their tolerance in dealing with the enormous task from its conception to its execution. Addressing the limit of our abilities and powers of imagination, philosophy takes up the technological concerns with a focus on the aesthetics of time.

The film uses music by the German techno-pioneer Kraftwerk, and utilizes the repetitive rhythm of their synthesizers as the background, which thus inserts a mechanical time into the silence of the super clean rooms. The regular computer beat adds something sensuous on a human scale to the stillness and lightens the mood in the tense atmosphere. The beat makes time flow, almost suggesting that 100,000 years might easily be counted. However, the endless continuity blurs one’s sense of time, as the title suggests, and viewers become lost between digital unit and eternity. The concept of time set by modernity does not speak to us clearly anymore. After all, the synthesizer only helps fathom the recognizable limits of the human senses.

photo ©Marc Doradzillo

Referring to the concept of “relational time” in music, the Japanese composer Jo Kondo, also mentions the directionality in contemporary music, as can be seen and heard in a documentary film about his work, A Shape of Time (2014). In the interview, Tom Johnson, a composer and music critic, reads out a letter that Kondo wrote to him in 2005 and explains his writing about American contemporary music in the late 1970s and 80s, which identifies the concept of non-teleological time and analyzes different kinds of non-teleological musical time as nature: “. . . In the process, music like Steven Reich’s, whose phrase, process, and structure are so clearly defined that the music loses the directionality intrinsic in the process. For example, a series of number such as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 . . . is so obvious that you don’t think of 6 as causing 7, and 7 as causing 8. It just happens. Another kind is found in Morton Feldman and my [Jo Kondo] music, which has neither systematic process, chance disciplines, nor indeterminacy, but instead consists of an accumulation of very short progressions.” In such music, he continues, “the musical directionality of each sound is so different that no overall directionality can be established.

It is a simple happening and a continuation one after another, without a teleological system.”8

8 A Shape of Time (2014), directed by Viola Rusche and Hauke Harder.

Non-teleological music, as described by Kondo above, and the juxtaposition of the regular rhythm of the synthesizer based on the assumption of a 100,000-year perspective in the film are identical in how they conceptualize time. Non-teleological music remains based on unit (each note) and unity (the music as a whole) as distinguishable entities, while simultaneously blurring the boundaries between the two. They proceed in a duration of time as music, but the time never has a direction. In the same way, the film juxtaposes the computational unit of rhythm without any goal and 100,000 years, which are almost infinite, with a goal. This is not about a paradoxical relation that replaces unit with unity or vice versa, or goal with/out goal, but is rather a general co-emergence of time and space, with no direction. Time completely merges with space in such a way that no time exists, regardless of whether it is inserted. We are therefore not in time, but instead we are time. Blurring the sense of time, the film presents a double negation of time, both the unit and the direction established by modernity.

The Imaginary Dimension of the Curatorial

In the previous paragraphs, I speculated on the notion of “blurring” in connection with the artworks described, but did not limit myself to pictorial or optical interpretations: it is instead about blurring as resistance against automatic acceptance and as a strategy for continuity, blurring as a critique of symbolic modes of searching, and blurring as a double negation of modernistic concepts of time. These conceptual explorations of blurring indicate that it is neither unclear nor imprecise, but instead achieves a precision in ambiguity. But where to does this guide us? What kind of direction of thinking could possibly emerge from such tentative curatorial speculation?

While the artistic practices imply other ways of thinking, which differ from those of science or norms, curatorial practice selects and connects and develops a sharable form, beyond the specificities of work or context. Revaluating the imaginary dimension of curating, the art theorist Helmut Draxler addresses the significance of selecting and making available within curatorial activities. He clarifies the proximate personal connections between the activities and the curator, and claims that their aim and value lie neither in “a remedy nor proposing a solution to overcome the crisis, but ultimately do define the various positions in the first place through acts of attribution and de-attribution” (Draxler, 2012). His remark suggests a fundamental difference between curatorial practice and theoretical analysis. Curatorial practice works with different accumulations and does not aim at examining in the same way as scholarly research, which focuses on progressing towards an objective. I would say that curatorial practice dis-occupies a space and changes the location of precisions of conceptual thoughts in the presentation of unmediated reality. It does not compete with other forms or directions of thinking, but rather loosens their directedness. That is why it facilitates working with and benefitting from existing discourses, languages, and methodologies, while simultaneously pointing out the limits and the problematic aspects, despite providing specific progressions and solutions. It is the creative act, with a tentative experiment connected with a non-directedness of thinking. Thereby, it should not be misunderstood as imprecise or irresponsible, although there is an increasing tendency to mix the two within the framework of “art and research.” It is instead a form of thinking, just as “theory” is, as well as a methodology for forming thinking. Curatorial practice is processing as well as processing back the realities in different ways so as to change the locations of precisions. Because processing information in the world opens up different modes and constellations of knowledge, simultaneously processing the words back hence opens up different paths and nodes of information, which are not predesigned according to specific criteria, structures, or systems. In this sense, the curatorial ability to select, capacitate, and circulate can contribute to new constellations for mapping and thinking, allowing us to see what we are, and, from there, to build new realities of what we could be.

The Curatorial as a Praxis of Disobedience

In its abilities to select, connect, and realize, curatorial activities are tied to the curator’s position of individual subjectivity, which is inevitably inscribed in politics and thus in economic, social, and institutional hierarchies. In this respect, “practices of curating are by no means innocent procedures in the service of their cause, . . . , but the acts of negotiation within the system” (Draxler, 2012). While I agree with his remark on the curatorial as a political act, here I would like to once again call attention to the body in curatorial activities and venture a step further to say that it is a praxis of facilitating disobedience so as to insist on other possible directions of thinking.

As an overall condition of living, curatorial practice synthesizes and reflects by throwing the body of the curator into the middle of social webs, through which the negotiations become visible. François Tosquelles, a Catalonian philosopher and psychoanalyst, emphasizes the connection of thought and geography, saying that when you walk, you have to keep your two arms free to be able catch things in the air. His insight reminds us of the necessity of using the whole body for searching and thinking. It is the body that enables us to walk and to connect with the politics of geography. The body occupies, interacts with, disturbs, and reveals time in space as well as space in time, and brings up the underlying values or values hidden in systems, relations, and the self. It is the body that sustains information on plural levels for a long time, enabling us to renew and to continue negotiating complexities. Thereby, the body of curator is crucial to engaging throughout the process.

After all, curatorial practice is nothing but a social sculpture that demands body and time, just like taking a walk. In the age of digital, networked technology, the ability to memorize is becoming less and less important. Rather, importance is placed on the ability to connect and restructure information in the construction of knowledge while faced with the technological and structural power outlined far into the past by modernity. In the nature of non-directionality practice, curatorial praxis is able to capacitate two or more contradicting cultures without compromises and changes. This curatorial specificity makes it possible to contribute today to renegotiating the divisions, polarizations and segmentations produced by the culture of symbolism. Instead of that culture’s acceleration and extension, curatorial practice takes on a significant position as a praxis of disobedience—disobedience vis-à-vis a symbolic aesthetics—in order to produce other ways and directions of thinking.

Share

Author

Miya Yoshida is an independent curator based in Berlin. She received a PhD in Fine Arts at the Malmö Art Academy, Lund University in 2007. Currently she works as a postdoctoral researcher/ lecturer at Leuphana University, Lüneburg, Germany. Miya Yoshida has been developing curatorial projects such as The Invisible Landscapes (Malmö in 2003, Bangkok in 2005, Lund in 2006), World in Your Hand (Dresden in 2010), Labour of Love, Revisited (Seoul, 2011), Amateurism! (Heidelberg, 2012) and Towards (Im)measurability of Art and Life (2013-).