It’s Us, Not You: Curatorial Notes on the 6th Asia Triennial Manchester

The Riddle of Values

The riddle of values—concerning both humans and things—reflects a long intellectual struggle throughout history. Brian Massumi’s assertion that “value is too valuable to be left in those hands” serves as a footnote in the dense web of value theories.1 From the very outset of Western philosophy, exemplified by Aristotle, value has been understood through the separation of use value and exchange value—categories that, in turn, determine embedded social relations and the structural causes underpinning any given society. This split between use and exchange value marks a genealogical divergence across value theory frameworks. Aristotle famously stated, “Of everything which we possess, there are two uses; for example, a shoe is used for wearing and is also used for exchange.”2 From this premise, property, ownership, value, and society are ordered.

Karl Marx’s concept of surplus value continues this line of thought, examining the structural conditions of capitalist society by highlighting the accursed excess that emerges from subtracting use value from exchange value. His allegory of the “dance of a wooden table,” particularly in connection with China’s Taiping Tianguo, can be read as an early omen of the operations of transcontinental late capitalism.3 It is no coincidence that Aristotle’s Politics begins with economics—or oikonomia—meaning the management of a household (oikos), as states and societies are conceptual extensions of domestic organization: from farming, cleaning, and cooking to slavery, wealth accumulation, and property defense.4 Aristotle’s political economy frames the economy as the “rule” of masters over slaves and of fathers over wives and children. Crude as it may sound today, he already recognized “those hands” in which values are governed—and how they are confined to the oppressed. In this light, the economy was always a political instrument. From Aristotle to Adam Smith to Marx, value is never merely an abstraction of measurability—it is a means of control.

Economy structures the household, the city, and the state, determining power relations before formal political institutions even emerge. This insight has been pursued by economists from Smith and Ricardo to Marx and Keynes: economic power underlies all governance. In East Asia, the Japanese translation of “economy” as keizai (經濟)—later adopted into Chinese during the May Fourth Movement—connotes “ordering the world and managing the people,” derived from the Taoist classic Baopuzi (抱朴子).To decouple economy from politics cannot be achieved externally; it must occur from within—through the very measurement of value. And this measurement, in its broadest sense, must be interrogated.

Immeasurability and Potentiality

This decoupling must be understood ontologically, wherein value, in its ordering of power relations, has lost the coherence of fixed measurement. From Plato’s idea of intrinsic property to Kant’s transcendental idealism and Marx’s metaphysical theory of value, measurement is central to value theory. The Enlightenment aimed to measure everything—including reason itself. Thus, any transgression of value requires first recognizing the importance of the immeasurable in subject-object relations: demographics, class, the human-nonhuman divide, and the ecology of things and their social functions and significance.

No transcendent power exists a priori to dictate how value is measured. Instead, immeasurable forces—affection, desire, and multitudinous energy—must be foregrounded to undermine the rigid link between economy and politics. Immeasurability, then, is not simply resistance to quantification—it transcends classification and normalization. In Deleuzian terms, to become monstrous is to become immeasurable, breaking away from value determinism.5 To transvalue means to go beyond fixed scales of value. Potentiality—especially that which Marx saw as the suppressed productivity of labor—must be reclaimed as an active, creative force that continuously generates new social relations, moving beyond capital’s chain reaction. A new community can emerge through pre-constitutional measurements, disintegrating the dominant values that guide society.

Transvaluation turns the economy—as a political tool of control and enslavement—into aesthetics: the realm of unmanageable immeasurability and potentiality. In this context, the vicious circulation of capital ceases to serve a mediated political function and instead becomes integral to meaning itself. The familial boundaries that once defined domesticity begin to blur, opening paths for new political relations and forms of subjectivity. This is a reversal of Aristotelian politics, wherein the oikos—the household—returns as a locus for political reimagination and emancipation. Here, economy must become eco-aesthetics: a term that designates a line of flight from the current social logic of late capitalism. Ultimately, economy and aesthetics are inseparable. Eco-aesthetics reintegrates the fundamental means of survival—labor, production, care—into a creative and imaginative reconstitution of political orders.

Eco-Aesthetics and a New Home

We must return to the original meaning of economy—the management of the household—and redefine it within an eco-aesthetic framework. This redefinition must go beyond traditional domestic limits, integrating the entangled forces of ecology, labor, and affect. Rather than viewing the household as a static domain ruled by the father/husband/master, we must imagine it as an evolving aesthetic-political entity, shaped by fluctuating relations of care, survival, and reciprocity. This transformation aligns with Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of anti-Oedipal subjectivity, where mental, social, and environmental ecologies intersect to create new relational forms. The becoming of schizoid subjectification dismantle rigid familial categories and property ownership hierarchical structures. Such a reconfiguration extends into a horizontal paradigm, where kinship-making and the cultivation of “odd kin”—as Donna Haraway proposes—construct alternative modes of belonging.6

These kinships, rather than resisting tradition, introduce an immeasurable potentiality that displaces economic rationality with open-ended communal life. The household becomes a site of speculative relation, where relations are not predefined by institutions but emerge through cohabitation and performative encounters. Eco-aesthetics reimagines economy as an aesthetic experience of making a new household, where production and reproduction are no longer reduced to labor and exchange but are woven into the poiesis of living—among humans, animals, plants, and nonhuman things alike. This shift is not a sociological revision, but a meta-political intervention—resonant with Chantal Mouffe and Jacques Rancière’s aesthetic-political strategies that question institutional order.7 The household transforms from a site of economic management into one of aesthetic and political imagination. Every act of care, sharing, and spatial organization becomes an aesthetic gesture that reconfigures our lived environment according to values that are life-enhancing and creatively enlivening, as opposed to preformulated and restrictive.

Proposal for Asia Triennial Manchester 6

Eco-aesthetics and transvaluation are not only philosophical frameworks but poetic practices. Taiwanese-based Malaysian director Tsai Ming-liang captures “other places” in Asia through cinema and installation. His diasporic gaze and Sinophone identity frame his trans-Asian aesthetic. With long, meditative shots that sculpt time, Tsai’s films evoke a new household in Taipei—growing in relation with long-time collaborators—while addressing themes of displacement, memory, and space. Drawing inspiration from historical narratives such as the journey of Buddhist scholar Xuanzang to India, Tsai’s films unfold cinematic time as heterotopia. Often concluding with nostalgic songs, he creates lingering atmospheres of loss and affect. His work attempts to preserve the traces of disappearance—post-Umbrella Movement Hong Kong, demolished public housing, defunct cinemas in Kuala Lumpur.

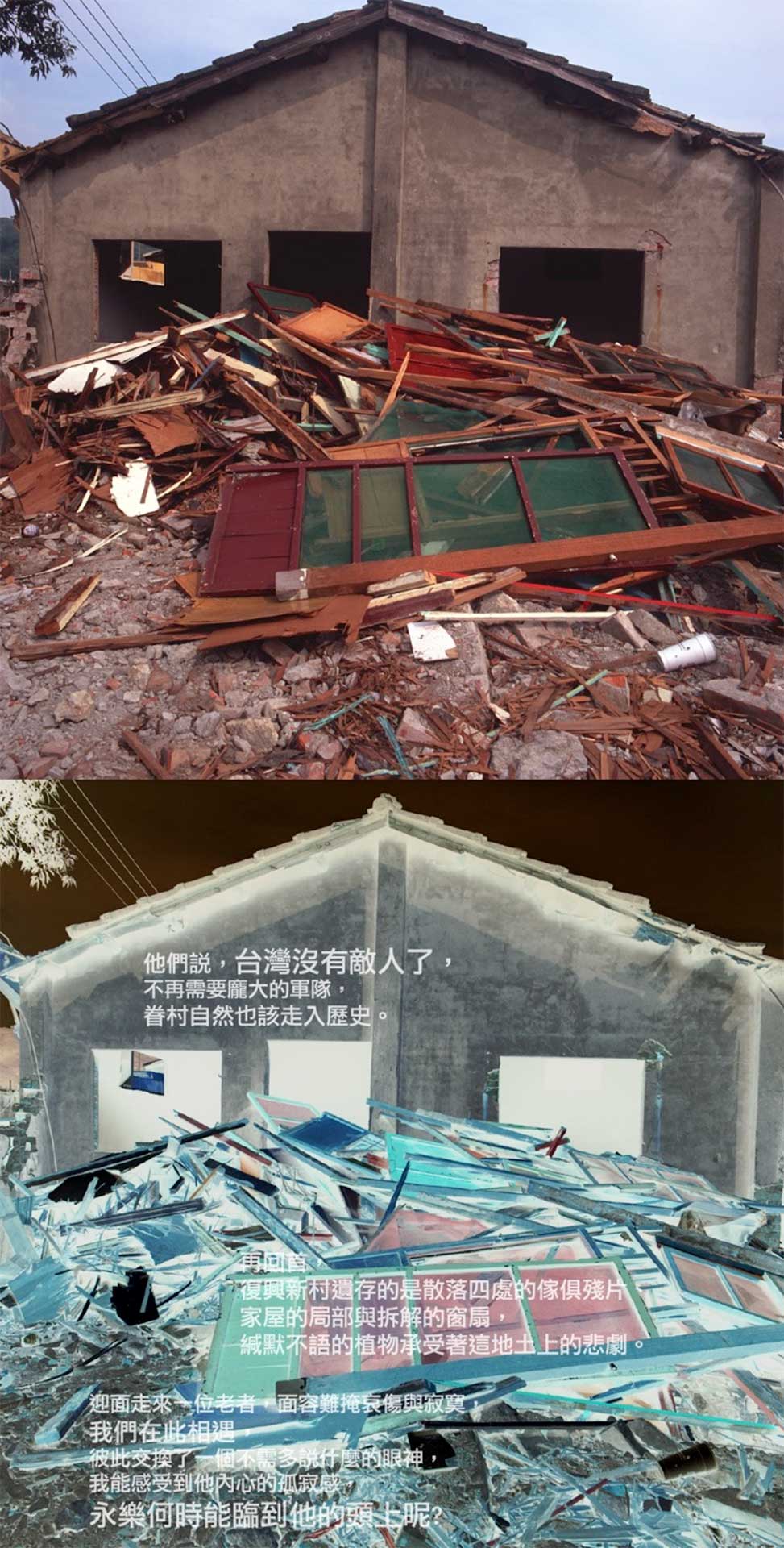

The biopolitics of home are further explored in Hou Shur-tze’s project Out of Place, a decade-long artistic research on the Military Dependents’ Villages (juàncūn) in Taiwan. These spaces, emerging from Cold War displacement, carry layered histories of the White Terror, diaspora, and the pivotal role of women in maintaining household life. Her multidisciplinary practice—including photography, writing, interviews, and activist exhibitions—treats the last remaining residents of juàncūn as kin, blending art with social movement.

By redefining economy as aesthetic practice, eco-aesthetics moves beyond extraction and toward sustainability based on care and reciprocity. This model challenges the attention economy that dominates exhibitions today, where metrics and visibility overshadow affect and memory. Eco-aesthetics becomes a laboratory for experimenting with what Lyotard may call libidinal economy—emphasizing recooperation and redistribution within social, psychological, and ecological terrains.8 Against the logic of capitalism, which seeks to quantify affect, eco-aesthetics insists on a broader conception of value. Transvaluation, then, is both an epistemological rupture and an ontological entity. It reorients how we assign worth to life, labor, and existence, taking an aesthetic turn toward meta-politics. Here, Lyotard’s notion of libidinal economy becomes crucial: focusing on the overflow of desire rather than measurable social media responses of likes and follows. In this emergent field, the household—reimagined through eco-aesthetics—becomes a site of artistic and political transformation. Production, survival, and kinship are no longer dictated by economic constraint but are integral to poetic creation. The new home, once a site of strict economic management, is now imagined as a space of aesthetic and political imagination, where new forms of kinship—among humans and non-humans alike—emerge. This reconceptualization of economy, aesthetics, and politics offers a radical departure from traditional frameworks, realized in ATM 6, inviting us to think of art not merely as a reflection of economic structures but as an active force in reshaping them.

1 Brian Massumi, 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018, 3.

2 Aristotle, Politics. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Kitchener, ON: Batoche Books, 1999, 41.

5 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987, 233.

1 Brian Massumi, 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018, 3.

2 Aristotle, Politics. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Kitchener, ON: Batoche Books, 1999, 41.

3 Marx brings these two events together: the rise of capitalism and China’s quasi proto-communism, in “ One may recall that China and the tables began to dance when the rest of the world appeared to be standing still – pour encourager les autres.” Karl Marx. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume 1. Translated by Ben Fowkes. London: Penguin Books, 1990 [1976], 163–64.

4 Aristotle, Politics, 14.

5 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987, 233.

6 Both “making-odd-kin” and “curious practice” are important concepts from Donna Haraway. The idea of odd kinship aligns well with curious practice on a conceptual level, as both challenge traditional structures and invite new ways of thinking about relationships and interactions. Donna J. Haraway. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016, 126.

7 Particularly on the antagonistic nature of democracy. Chantal Mouffe. On the Political. London: Routledge, 2005.

8 One of the figures Lyotard employs is “the great ephemeral skin,” in which intensification and polymorphism operate in a differential rather than oppositional trajectory. Only an army of metaphors

mouths, lips, fingertips, nails – can capture such a radical condition of jouissance. ean-François Lyotard. Libidinal Economy. Translated by Iain Hamilton Grant. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993, 1–2.

Share

Author

Hongjohn Lin is an artist, writer and curator. Graduated from New York University in Arts and Humanities with Ph.D. He has participated in exhibitions including Taipei Biennial(2004), the Asia Triennial Manchester 2008, the Rotterdam Film Festival 2008, and the 2012 Taipei Biennial, Guangzhou Triennial (2015), and China Asia Biennial (2014). Lin was curator of the Taiwan Pavilion Atopia, Venice Biennial 2007, co-curator of 2010 Taipei Biennial (with Tirdad Zolghadr), and numerous curatorial projects such as Taizhong’s The Good Place (2002) and Live Ammo (2012). Lin is serving as Professor at the Taipei National University of the Arts. For the past 10 years, he has been working on project based on George Psalmanazar, A fake Taiwanese in the early Enlightenment. He is interested in transdisciplinary arts, politics of aesthetics, and curating. His writings can be found in Artco magazine, Yishu magazine, international journals, and publications of Art as a Thinking Process (2010), Artistic Research (2012), Experimental Aesthetic(2014), Altering Archive: The Politics of Memory in Sinophone Cinemas and Image Culture (2017). He wrote the Introductions for Chinese edition of Art Power (Boris Groys) and Artificial Hells (Clair Bishop) . His books in Chinese include Poetics of Curating (2018), Beyond the Boundary: Interdisciplinary Arts in Taiwan, Writings on Locality, Curating Subjects: Practices of Contemporary Exhibitions.