Curating and Re‑public / Re‑commons

November 15, 2024, has passed more than half a year ago. The Jakarta Biennale 2024 (JB 2024) which was organized to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the event (1974 – 2024) was finally held for 46 days. The main concentration of this event took place in Taman Ismail Marzuki, Jakarta. But several other collective spaces in Jakarta also celebrated it. In addition to exhibitions at Galeri Emiria Soennasa, Galeri Sudjojono, Galeri Oesmar Effendi, JB 2024 also featured 70 public programs at Komunitas Salihara, Universitas Binus, Komunitas Paseban, Gudskul Ekosistem, Setali Indonesia, and Atelir Ceremai. JB 2024 attracted 35,479 visitors based on registration records at Taman Ismail Marzuki alone, not counting visitors and participants at other locations. As part of one of the Majelis Jakarta (Jakarta Assembly) member collectives, Gudskul Ekosistem, I was involved in JB 2024.

Together with several other friends, my involvement began with a meeting at the invitation of the Komite Seni Rupa Dewan Kesenian Jakarta (Fine Arts Committee of Jakarta Arts Council – DKJ). One could say that I was there from the beginning, in the context of preparation until the implementation of JB 2024. It was quite a valuable journey. Since approximately half a year has passed, it is a good time to try to make reflections on that experience. Given that the fatigue from “being battered by fine arts”—to quote Esha Tegar Putra’s introductory title for the archive section of JB 2024—has subsided, it can be said that there is now enough distance from the event to be able to recollect it. Therefore, this writing is more of a personal reflection about my personal involvement, made possible by being part of a collective and meta-collective. Because of its nature, this reflection can be seen as an attempt to see (from inside) JB 2024. If we imagine JB 2024 as a body, then this paper is an attempt to see the innards inside the body rather than merely the appearance of the outside of the body. Although, as a consequence of being part of one body, the two are interconnected and presuppose one another.

Longing in Silence

In its 50th year, the Jakarta Biennale is often envisioned as an established entity. Events such as biennales are often funded by the government, or a certain entity. In this context, the Jakarta Biennale is close to, or can be seen as, an event that is often supported by the provincial government of Jakarta, through the office in charge of culture in the province. In this context, I have had an ironic experience. I once had the opportunity to represent the Majelis Jakarta, and together with the Komite Seni Rupa DKJ, to visit Dinas Kebudayaan DKI Jakarta (Culture Office of the Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta). The purpose was clear, to have an audience to get support for JB 2024. I forget, in our presentation at that time, how many rupiahs were displayed. What is clear is that it was less than 3 percent of 150 billion Rupiah, the amount of corruption in Dinas Kebudayaan DKI Jakarta that was widely reported some time ago1. Imagine with that much corrupt public money, how many international festivals in Jakarta could be held without limping? This phenomenon, the lack of support from the same local government that has been proved to be embezzling funds intended for cultural activities, is something very sad. We are not only talking about how the government does not understand the important roles of culture and the arts, but something far worse than that.

If you look at the JB 2024 publications—which can still be accessed on the Instagram account @jakartabiennale and the website jakartabiennale.id—there are logos of the Culture Office, UP PKJ TIM, Jakpro, and TIM—entities that are part of the Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta. However, those logos are just proof that they gave JB the opportunity to organize the 2024 edition in the Taman Ismail Marzuki area. This was possible because there was already a prior agreement regarding the free use of space at TIM by programs under DKJ. So, it can be said that the support from Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta institutions did not play a pivotal role. Clearly, JB is not a local government priority.

In an informal conversation I had with Ade Darmawan some time ago, the Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta has long indicated that it does not see the importance of JB. The mechanisms and schemes of support from the local government for JB through DKJ are often capricious and uncertain. Like many other third-world biennials, JB is initiated by artists, not the local government, the state, or any other authority.2 The full involvement of Jakarta’s art and culture people in the JB as the driving force has colored and even enabled the event to reach the age of half a century. The consequence of this is the imagination of JB’s independence and flexibility in finding other ways to garner support outside of the schemes of the Jakarta Government authorities, and also the DKJ. There is an awareness that JB’s resources should not depend on one particular entity that is top down. A step in this direction was manifested in the establishment of a foundation that oversees JB.3

Using the name biennale, JB events are supposed to be held every two years. Before 2024, this event was last held in 2021 (precisely from November 21, 2021 – January 21, 2022) which means three years before JB 2024 took place. Three years less one month and twenty days. From this time calculation, it is clear that there is a deliberate intention to postpone and move the organizing year from odd years to even years. At the same time, the scheduling also corresponded to the first event held in 1974.

Delays and struggles to becoming organized are not a one-time occurrence. Many times, JB has suffered from various problems. In Esha Tegar Putra’s notes, JB has been criticized and silenced by artists, delayed due to regime censorship, delayed because the organizing capital could not be collected, or also deliberately delayed because of the promise to hasten the creation of a representative exhibition space at PKJ TIM (Pusat Kesenian Jakarta – Taman Ismail Marzuki/Jakarta Art Center – Taman Ismail Marzuki).4 In the introduction to the archive exhibition section at the last JB 2024, Esha wrote this after a lot of coverage: “…for half a century, this biennale has been battered by various problems, but it is still secretly missed.“

The longing for the Jakarta Biennale to be held again began to stir when the Komite Seni Rupa DKJ invited several parties in 2023 to discuss the event and remind them of the JB 50th anniversary in 2024. This initiative for me shows the manifestation of the historical responsibility of DKJ, because it was from the womb of this institution that Pameran Besar Seni Lukis Indonesia (The Grand Exhibition of Indonesian Painting – PBSLI) of 1974—the forerunner of the JB—was born. Since 1974, this event has also been envisioned as a biennale, as stated in the catalog:

…because Dewan Kesenian Jakarta in December 1974 has planned various special activities (literary meetings, musician meetings, youth theater festivals, and so on), it is appropriate to hold a Pameran Besar Lukisan (Grand Exhibition of Paintings) (Biennale Lukisan) in December too, for one month. In accordance with the word “biennale” which means every two years, we can make this year’s Pameran Besar Lukisan December (December Grand Exhibition of Paintings) the beginning of a tradition of such painting exhibitions5

Regarding Majelis Jakarta (The Jakarta Assembly)

The spirit of JB 2024 is thus celebratory. After Komite Seni Rupa DKJ was invited to discuss the matter in 2023, the process of realizing Majelis Jakarta began. It is true, as several observers have pointed out, that the concept of majelis is closely related to the concept of lumbung, which has been widely introduced by ruangrupa. For example, Elly Kent states that, “…the exhibition organisers have adopted one of the methodological approaches embedded in ruangrupa’s direction of documenta15, the majelis, which can loosely be translated as a committee or council. The Jakarta Biennale’s majelis is in turn made up of 18 artists associations and collectives, largely from Java.”6

The meaning or essence of a majelis (assembly) is not who is present but the dynamics of conversation and collective decision-making. This means that we need to see ‘majelis’ as first of all a verb and not a noun. Thus, what matters next, secondly, is the dynamics of conversation and the dynamics of joint decision making, not what entities are part of or members of the assembly, as if it was a noun. Of course, again, the process, and who is in the process, cannot be separated. What I mean is that the concentration of our discussion of this “majelis” needs to be placed first in the process. My suspicion is that by seeing “majelis” as a verb, we are slowly refining it as a ‘method’; by seeing it as a noun, we are slowly reducing it to a commodity.

Another aspect that is important to consider about the Majelis Jakarta is that it works as a strategy of decentralizing power, promoting the spirit of gotong royong (simply translated as “working together”) and a way of returning to the spirit of JB since PBSLI 1974, namely the initiative of cultural arts practitioners. According to my conversation with Ade Darmawan, the discussion about encouraging JB under the management of many cultural arts entities with the spirit of gotong royong has been rolling since JB 2021. The mutual cooperation model is considered more appropriate in managing JB. As stated earlier, the support model from the Regional Government is always uncertain and constantly changing. This is a result of a changing political and economic power. However, what does not change is the spirit of mutual cooperation and collaborative work, as well as the power for sustainability within art collectives. A meta-collective—as the organizer of JB—is thus a consequence of this panorama.

Majelis Jakarta is also a strategy to get out of the trap of the centralized biennale model. JB was not centralized and/or top down from the beginning, in the context of the entity that initiated and ran it. However, in the context of its artistic articulation, it became a model of centering on a single curator for a long time. As we know, the concept of a single curator was introduced in JB 1993 by Jim Supangkat.7 In its development, this model began to be questioned and challenged, and became increasingly incompatible with existing developments. Simultaneously, the conventional exhibition concept no longer seems to have the capacity to accommodate the diverse developments in artistic expression today.8

Majelis Jakarta was formed from entities that already existed in the database or network of JB (or the foundation that oversees JB) itself, and from the Komite Seni Rupa DKJ. I think, its members are the result of observations which consider factors such as the ways of collective work, the diversity of artistic and social practices, the distribution in Jakarta, and, most importantly, the willingness and agreement to work together in Majelis Jakarta with the spirit of lumbung. Of the 20 entities in Majelis Jakarta, not all are actively involved. Some only joined the meetings once or twice, and then not at all. There are those who are eager to get involved in JB 2024 to the nth degree, and there are those who are not so active. There are different models of participation. Like a vegetable “rumpu rampe,” the activeness and level of gotong royong varies, but produces something delicious to experience. It is also important to remember that the volume of involvement does not have to be the same for everyone, as for example, “each entity must prepare 5 hours per day for JB 2024.” The principle of equity gives us an understanding that all parties provide the power and time that they can give within the framework of gotong royong. So, instead of every entity giving 5 hours a day equally, for example, there could be entities that are only able to give 1 hour because they are busy with other activities, while others give 6 hours, others 3 hours, and so on.

Since the first meeting attended by 20 entities, three issues have been mapped together, namely the Imagination of Implementation, Funding for Implementation, and Mapping of Jakarta Art Resources. Consequentially, three working groups were formed, each of them responsible for one of the aforementioned objectives. Each group then worked in a limited time and produced results that were certainly far from ideal. However, these modest results—in my opinion—provided hope.

It could be argued that JB 2024 is the first step in a process of joint working efforts between these collectives that are part of the Majelis Jakarta. This process is described by Ibrahim

Soetomo as “…the formation of a supercollective, a large collective containing collectives, within which there are also collectives containing collectives, for example Gudskul Ekosistem. Collective, containing collective, containing collective.9″ I prefer to call this phenomenon a meta-collective.10 Meta-collectives, as Martin Suryajaya et al. put it, exist because of “…the need to consolidate the diversity of alternative spaces into a working-together platform.”11 Furthermore, Suryajaya et al. emphasize that the process of becoming a meta-collective is a necessity for the journey of the art ecosystem that we call “collective.” It is a consequence of a pattern of working together, a pattern of mutual cooperation, so as to achieve a common goal.

This meta-collective, namely Majelis Jakarta, in JB 2024 also collaborated with three parties, Curating Topography Trilogy, Our People are Our Mountains, and Baku Konek. As mentioned in the wall text—which again, along with many other works-in-progress, was only installed some time after the opening—all three were present for different reasons. Curating Topography Trilogy is an old JB collaboration. At JB 2021, it was already present with collaborative works between Southeast Asian, Taiwanese, and South Asian collectives and artists with Indonesian art collectives and artists under the program name “Ring Project: Metaphor About Islands.” Collaborative work and networking are also nurturing old collaborations. In a way, the collaboration with Curating Topography Trilogy was triggered by the saying: “If you make new friends, don’t leave old friends behind.” Furthermore, although dominated by collaborations with Taiwanese first nation collectives and artists, Curating Topography Trilogy gives the Majelis Jakarta the possibility for getting to know its neighbors more closely. The orientation offered by this collaboration is horizontal.

Meanwhile, Our People are Our Mountains, a collaboration between the Majelis Jakarta and a Palestinian artist collective, is a form of partisanship. I don’t think it needs to be explained at length, what kind of partiality is meant. Baku Konek is assumed to be a collaborator that shows the same spirit of collectivism as Majelis Jakarta. Within the existing limitations, JB 2024 seeks to revive the spirit of PBSLI 1974 by presenting Baku Konek because, as I quote from the wall text, “…Lab Indonesia: Baku Konek also strives for the sustainability of the art ecosystem in Indonesia and encourages the exploration of various local contexts, which is the goal of the Jakarta Biennale itself since it was first held under the name PBSLI in 1974.”

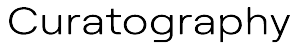

In a Process of Becoming

Admittedly, the above explanation about the Majelis Jakarta’s collaborators in JB 2024 was not well distributed because it was not present from the beginning. I forget how many days after the opening that the text was presented. Some works from collectives within the Majelis Jakarta went through the same path; installed and refined after the opening of JB 2024. Some of the works from Curating Topography Trilogy were held up in Customs so they were not displayed at the opening. Visitors also found that—as Ibrahim Soetomo, Asep Topan and Elly Kent pointed out in their writings—there was no clear division delineating the flow of works displayed, making it difficult to follow the exhibition path and get a clear understanding of all contributions. Innas Tsuroiya, in her short review, calls any or all this chaos “…a deliberate rejection of spatial organization.12″ Don’t chaos and sprawl have their own aesthetics—in the sense of the science of beauty? The phrase ‘deliberate rejection’ sounds poetic for describing the efforts to find one’s own form, to find one’s own way of working, to find mechanisms that are more relevant and appropriate to the existing conditions.

Technical matters are always related to vision matters. Often the vision and technicalities are at odds; there are those whose vision is great but not followed by good technicalities. That is, the technical doesn’t translate the vision. Sometimes the technical is perfect but it is not a materialization of the vision. This means that the technical and the vision do not go hand in hand. Seeing the vision and the technical together allows us to understand an event better; judgment is not only generated through the visible, but also by the invisible. And vice versa. The vision of the JB 2024 process is an attempt to find the right tone for the various working patterns of each entity within the Majelis Jakarta. It is a form of experimentation, exploration, and speculation, which comes because of seeking a decentralized form of power.

This search for undertones is not a matter of paper. Most of the collectives in the Majelis Jakarta already knew each other; both the collectives themselves and the individual members of those collectives. However, in my opinion, knowing each other does not automatically guarantee that the basic tone will be the same. The process of attuning to each other is still a process of and in becoming. The collectives that are members of the Majelis Jakarta also practice, more or less, more than one and less than ten values of lumbung13 in their own way. This also does not guarantee that the rhythm of working together will automatically be harmonious. It takes time for it to settle, because it is a process that is not yet (and maybe never) finished. And this is where lumbung is interesting, because it is “…a space for an exploration of innovation without formal institutional boundaries.14” The traditional meaning of lumbung is a place to store agricultural products, which in turn will be taken to be utilized as needed during the famine period. The process of filling the barn is a process of gotong royong and the utilization of its contents is also through a negotiation process called musyawarah mufakat. The articulation of these processes in the Majelis Jakarta was embodied in the JB 2024 exhibition and public program from October 1 – November 15, 2024.

From the foregoing, it is clear that what constitutes JB 2024’s vision are matters within itself. It is an attempt to test the meta-collective work of the Majelis Jakarta, a search for the undertones of different forms of work, and a limited reading of its own history. The big question that JB 2024 tried to answer to was whether it is possible for a Jakarta Biennale to be organized and owned jointly by art entities in Jakarta. Consequently, things that are outside of itself are not unimportant, but are temporarily subordinated or locked away in order to answer the above question.

Closing: The Audience and the Meta-Collective

In the end, every art event must deal with viewers. Quantitatively, the number of viewers of more than 35,479 is quite good. However, when compared to the 2021 edition, this figure shows a decline. JB 2021 was visited by 98,000 people. However, in the presence of the arts and culture community, quantitative is not the main measure. There is a latent demand that the public must be educated, educated about something that lies behind or beyond an art event itself. Criticism of this view has long been echoed. Ronny Agustinus, for example, wrote in 2001 about the obsolescence of the view of artists as agents who provide awareness to society.15 Implicitly, this view places the position of the artists (or the art world) above society. In fact, artists are only one entity in society. Their position is the same. Often, artists learn from society, taking inspiration from society to create their work.

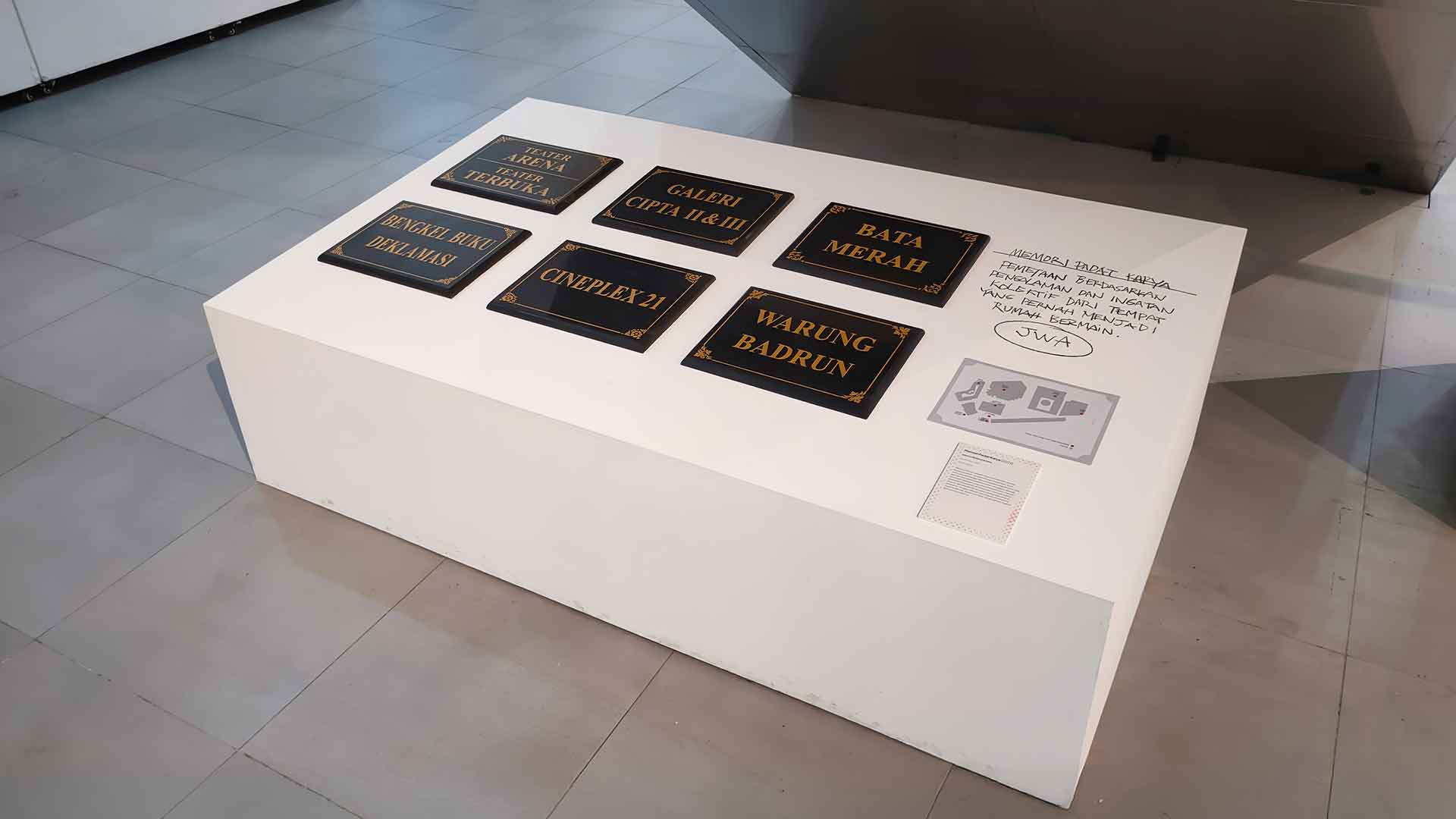

After all, the phenomenon of the relationship between visitors and artists at recent exhibitions shows the tendency that visitors and artists are both artists. The difference is that the artist has become an ‘artist’ first, followed by the visitor. What I mean is this: the artist makes a work of art that is exhibited in an exhibition space. Then, visitors come to the exhibition. The visitor does not come empty-handed; they are holding a handphone. Facing the artworks arranged in the exhibition hall, the visitors create new artworks through the cameras of their handphones. Immediately, with a delay of perhaps only a minute or two, this new artwork has been exhibited on their social media account. Reaching out to other art viewers who are not in the exhibition space thus expands the reception of this artistic scene.

If there is something that needs to be educated by the curator and the artist, it is what kind of meaning they want to convey to art viewers via this phenomenon; in which (1) viewers come to the exhibition space not only with the motive of enjoying artworks, but also for creating artworks and (2) audiences who are not in the exhibition space but can enjoy the artworks, curated by the curator and created—sometimes over a long period of time—by the artist, through the mediation of social media, relayed by visitors at the exhibition. Often, when creating this new work of art with their handphone—whether in the form of photos or videos that are sometimes broadcasted live—the visitor also makes certain interventions on the artworks in the exhibition space. We can imagine the millions of variants of meaning that will be created in this process.

This practice or phenomenon will become more and more prevalent in the years to come. If the unprecedented process of the Majelis Jakarta that we talked about above goes smoothly, this will also be an issue that the meta-collective will need to reflect on. One important thing is that being a meta-collective is a consequence of working together, a logical consequence of gotong royong.

Perhaps the consequences of being a meta-collective can be imagined by looking at something similar, namely the context of the formation of the nation, especially regarding national identity. Each of us has an individual identity. For example, one Bagus is from Kediri and works as a gallery curator, another Bagus is from Jogja and works as a bank employee, and there is also a teacher in rural Papua named Bagus who is originally from Denpasar. These three Baguses have a shared identity, such as being Muslim. There is also a group of Ayu who are university students, a group of Lita who embrace Kejawen, and a group of Sigit who are part of the Indonesian Vespa Lovers Community. Bagus’s group, Ayu’s group, Sigit’s group, and Lita’s group then gathered and formed a larger group, with an Indonesian identity.

I was reminded of what Hilmar Farid said in the 2015 JB symposium, Makan Ngga Makan Asal Kumpul16, that there is one old collectivity that has been forgotten—this collective has existed since the 18th century—namely the nation. Perhaps it is true what Hilmar Farid said, because the concept of nation or the nation itself has been discredited in such a way—by all kinds of contemporary theories and all kinds of contemporary aversions to politics—that we forget that the nation has provided examples and exercises of being a collective, how to be a collective above the collective, and to be a collective above the collective above the collective, aka a meta-collective. If we really are a nation and a state, imagining ourselves as part of the nation and the state, having a partiality for the “others over there who are unknown to me but are an inseparable part of me too,” then the meta-collective phenomenon is not something surprising. The difference is that the nation’s collective might feel too abstract and too distant because it presupposes only shared imagination with those who have never met; for example—I think if we read Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities, this matter is very clear—whereas the art collective feels more real because its practices are clear and presentable. Or perhaps the art collective is the practice of that shared imagination. It is an articulation, an expression—to quote Hilmar Farid at the symposium above—of a larger collectivity, let’s call it a nation.

1 Devira Prastiwi, “6 Fakta Terkait Kasus Dugaan Korupsi di Dinas Kebudayaan Jakarta, Ditetapkan Tiga Tersangka”, liputan6.com, January 03, 2025, accessed on April 25, 2025.

2 Asep Topan, “Dimensi Kelembagaan dalam Seni Rupa Kita: Pembacaan terhadap Jakarta Biennale dan Museum MACAN,” in Spektrum 2021 – Enam Perspektif Seni Rupa Kontemporer Indonesia, eds. Farah Wardani & Ninus Andarnuswari (Jakarta: Dewan Kesenian Jakarta, 2021), 51-74.

3 Author’s conversation with Ade Darmawan on January 28, 2025.

4 Esha Tegar Putra, “Biennale yang Dikecam, Diamuk, dan Dirindukan: Telaah Arsip 50 Tahun Jakarta Biennale (Bagian Pertama)”, garak.id, November 01, 2024, accessed on January 20, 2025.

5 Dewan Kesenian Jakarta, “Kata Pengantar,” in Pameran Senilukis Indonesia 1974: 18 s/d -31 Desember 1974 – Katalog Pameran. Dewan Kesenian Jakarta (Jakarta: Dewan Kesenian Jakarta).

6 Elly Kent, “Contemporary Jakarta: A Tale Of Two Art Events,” Art and Australia 59, No. 2, https://artandaustralia.com/59_2/contemporary-jakarta-a-tale-of-two-art-events, accessed on April 24, 2025. It should be emphasized here that the members of the Jakarta assembly were indeed from Java but more specifically all from Jabodetabek. What Kent says can also be seen in Asep Topan’s article. See Asep Topan, “Biennale Anonim: Kekuratoran Kolektif dalam Jakarta Biennale 2024,” senirupa.id, November 20, 2024, accessed on January 26, 2025 and Ibrahim Soetomo, “Jakarta Biennale 2024: Pemaknaan Seni dan Kolektif yang Memancing Tanda Tanya,” whiteboardjournal.com, November 01, accessed on January 27, 2025.

7 Agung Hujatnikajennong, Kurasi dan Kuasa: Kurator dalam Medan Seni Rupa Kontemporer di Indonesia, (Tangerang Selatan: Marjin Kiri, 2015), 202.

8 Author’s conversation with Ade Darmawan on January 28, 2025.

9 Ibrahim Soetomo, “Jakarta Biennale 2024”

10 Berto Tukan, “In the Same Soil-Water, Different Seasons: The Emergence of Art Collectives in the Discussion of FIXER 2021”, in Spelling FIXER 2021: Readings of Indonesian Art Collectives in the Last Ten Years, ed. Bagus Purwoadi (Jakarta: Yayasan Gudskul Studi Kolektif), 21.

11 Martin Suryajaya, Nyak Ina Raseuki & Amy Zahrawan, “Kolektif dan Menjadi Kolektif: Evolusi Wacana Kolektif Seni Rupa di Jakarta,” Jurnal Masyarakat dan Budaya, Volume 25, No. 1, Tahun 2023, 25.

12 Innas Tsuroiya, “Jakarta Biennale 2024: 50 Years of the Jakarta Biennale, 1974-2024”, December 05, 2024, accessed on January 28, 2025.

13 Lumbung values are humor, generosity, curiosity, adequacy, independence, rooted in locality, sustainability, transparency – trust, regeneration, and ethics and politics. Ade Darmawan, “Taking Root and Spreading Out: Lumbung as an Economic and Aesthetic Model of Art Organisation”, Jakarta Arts Council Annual Cultural Speech conference, 10 November 2022, 49-50.

14 Ade Darmawan, “Taking Root and Spreading Out”, 48.

15 Martin Suryajaya, et al, “Collective and Becoming Collective”, 22. See also Ronny Agustinus, “A Cold Beer Conversation and 3 Years After” in Absolut Versus, ed. & trans. Amanda Katherine Rath (Jakarta: ruangrupa, 2001), 57-58.

16 Hilmar Farid, “Simposium ‘Makan Nggak Makan Asal Kumpul’, Jakarta Biennale 2015”, November 16, 2015, 1 hour 11 minutes, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PdxMjsfdmIg&t=2529s, accessed on January 28, 2025.

Share

Author

Berto Tukan is a member of Gudskul Ekosistem, Jakarta. He is a writer and independent researcher who lives in Jakarta and also a part of Jurnal Karbon. Now, he is active as a subject coordinator at Gudskul: Contemporary Collective Study and Art Ecosystem, an alternative study institution established by three art communities in Jakarta: ruangrupa, serrum and Grafis Huru Hara. In 2019 – 2021, together with several friends in Gudskul Ekosistem, he researched the development of art collectives in Indonesia. The results of that research can be read in the book, Articulating Fixer 2021: An Appraisal of Indonesian Art Collectives in the Last Decade (Yayasan Gudskul Studi Kolektif, 2021).

Berto once studied German Literature at Faculty of Humanities, University of Indonesia. His bachelor’s was concluded in the Philosophy Department, Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat Driyarkara, Jakarta. In 2018 he finished his Masters at the same university. His short story collection, Seikat Kisah Tentang yang Bohong was published in 2016, and his poetry collection, Sudah Lama Tidak Bercinta Ketika Bercinta Tidak Lama in 2018. He has also published Aku Mengenangmu dengan Pening yang Butuh Panadol and #kitadirumahsaja dan Khawatir Akan Dunia (a poetry collection) in 2021. Apart from short stories and poetry, Berto also has written a number of essays appearing in various print and online media, and spends some time doing many art researches. In addition to these accomplishments, he was often involved with the Jakarta Arts Council, doing research for their program; for example, for the publishing of Seni Rupa Indonesia dalam Kritik dan Esai (2012) and Knowledge-Based Art Essay in Three Cities Research (Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Bandung). With some of his friends he published alternative print media, such as, Pendar Pena, Problem Filsafat and .