The Heterogeneous South

In the context of curatorship for fine arts, various studies conducted by Flores (2008)5, Hujatnikajennong (2015)6 and Supangkat (2018)7 implicitly show that curatorial practices only occurred in Java—yet they are generalized as “curatorial practices in Indonesia.” This shows that there has never been a thorough investigation of and record on curatorship in the islands, other than Java. Hence, this writing tries to highlight those curatorial practices outside Java that also occurred, especially in Jayapura and Maumere, which I will describe specifically.

1 Munandar, Agus Aris, et al. Sejarah Permuseuman di Indonesia. Jakarta: Direktorat Permuseuman, 2011. pp.14-15.

2 Kusuma, Erwien. Kuasa Kuratorial dalam Tata Pamer Museum, Academia. Accessed online on May 13, 2022. pp. 3. https://www.academia.edu/41800140/Kuasa_Kuratorial_dalam_Tata_Pamer_Museum

4 Susantio, Djulianto. Moh. Amir Sutaarga, Kamus Hidup Permuseuman in Majalah Museografia Vol. VI, No. 9 – Juli 2012. Jakarta: Direktorat Pelestarian Cagar Budaya dan Permuseuman. 2012. Accessed online on May 13, 2022. https://museumku.wordpress.com/2012/09/14/moh-amir-sutaarga-kamus-hidup-permuseuman/

5 Flores, Patrick D.. Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Museum. 2008.

6 Hujatnikajennong, Agung. Kurasi dan Kuasa: Kekuratoran dalam Medan Seni Rupa Kontemporer di Indonesia. Jakarta: Marjin Kiri. 2015.

7 Supangkat, Jim. Kemunculan Kerja Kurasi di Indonesia pada 1990 dan Latar Belakangnya. Proceedings of the Imagined Curatorial symposium at Bandung Institute of Technology. August 8-10, 2018.

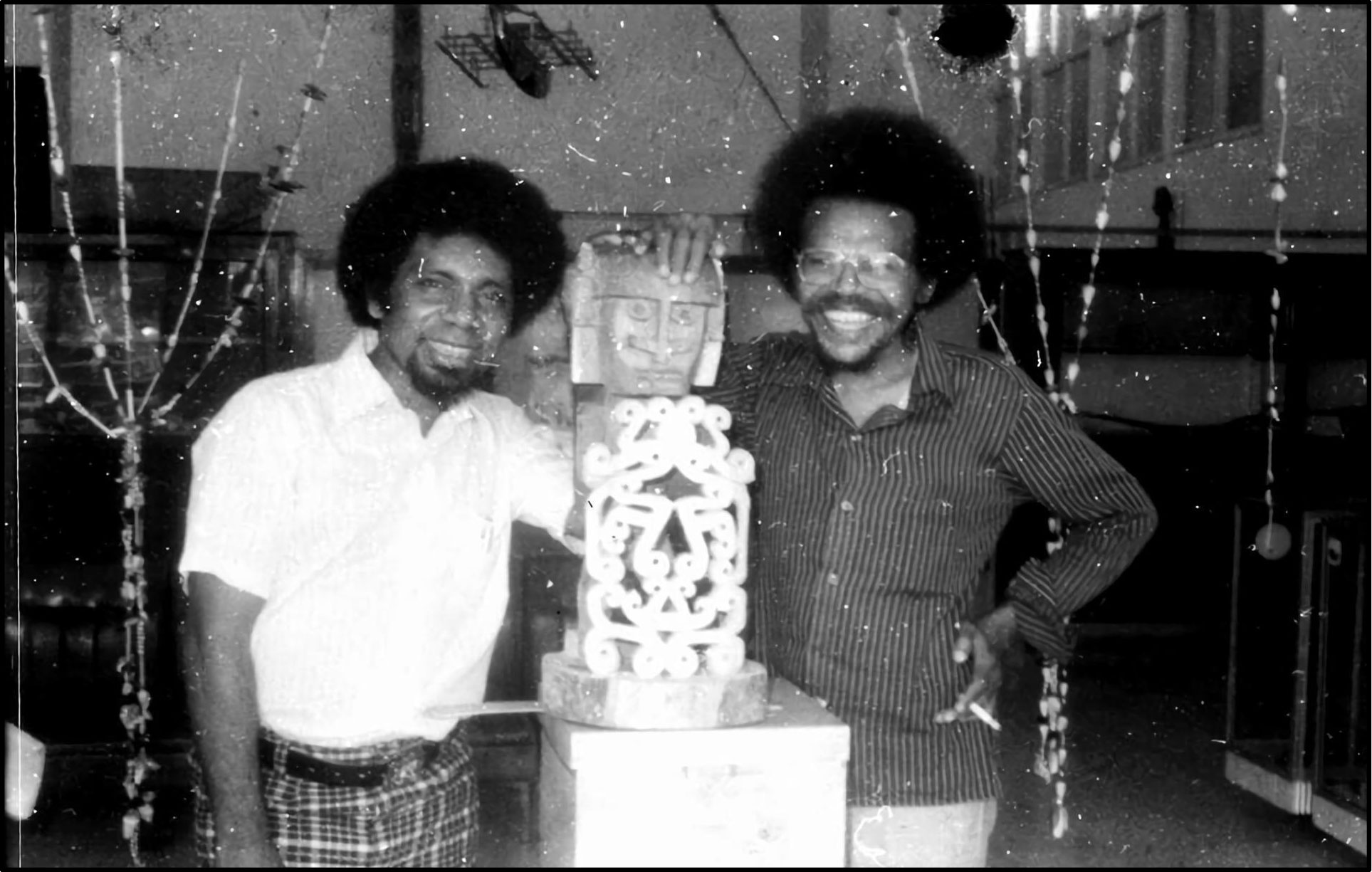

One example was that a year after being appointed curator at the Loka Budaya Museum, together with his best friend, Sam Kapisa, he formed a music group called Mambesak. The name comes from the Biak language means the bird of paradise and its members were museum employees and students of the Anthropology Department. Every afternoon, the group used to perform music and dance in the vast courtyard in front of the museum. Some of the instruments they used were from the museum collection, and also musical instruments collected from various indigenous communities in Papua. Arnold also changed the image of the museum by calling it Istana Mambesak (Mambesak Palace). His various musical activities turned out to be a strategy for attracting locals to visit the museum.9 For the Jayapura community at that time, the museum was certainly a peculiar place, because the local community did not recognize the concept of museum culture. With music, Arnold brought the concept and significance of the museum closer to the society. After their musical performance, they usually invited the public to enter the museum, and Mambesak members would then explain the various collections to the public.10 Through this practice, Arnold changed the image of the museum, from being simply a repository of inanimate objects, into a living cultural laboratory.

8 Stolley, Richard B.. An Anguished Search for Signs of A Missing Son in LIFE Magazine December 1, 1961. Accessed online on May 13, 2022. pp. 40-46. https://books.google.co.id/books?id=AVQEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

9 Goo, Andreas (ed.). Grup Mambesak: simbol kebangkitan kebudayaan orang Papua Proto. Jayapura: Uncen Press dan Lembaga Studi Meeologi Press. 2019.

11 Ibrahim, Raka. Arnold Ap: Papua’s lost cultural crusader gets long-delayed recognition in Jakarta Post September 2, 2021. Accessed online on May 13, 2022. https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2021/09/02/arnold-ap-papuas-lost-cultural-crusader-gets-long-delayed-recognition.html

The church then sent Piet Petu to continue the study of spirituality in Nemi, Rome, between 1961-1962. In that timeframe, he took the time to visit a number of museums in Europe, in order to learn about museum management practices. When he was returning to Indonesia, the top leader of the SVD Order asked him to open a museum in Flores. This request was eventually fulfilled in 1983, when he built the Bikon Blewut Museum in the Catholic high school complex, where he taught. He wanted the museum he established to support the traditional teachings that had begun to be twisted (bikon) and were becoming rotten (blewut), especially after the presence of modernization brought by the Catholic church.13

Piet Petu’s curatorial approach was strongly influenced by the ethnography he had done, whereby cultural artefacts were exhibited in accordance with the ritualistic context of the local community. For instance, when he wanted to display the sacred inculturation concept of customary marriage, he would make a composition of elephant ivory, which is widely used as a dowry by the Lamaholot tribe, with Moko Alor inherited from Đông Sơn culture. Conversely, when he wanted to narrate the practice of collective governance in traditional societies, he would display elephant tusks side by side, with Mahe Watu, or altars of worship in the Krowe Tribe.14 This method of presentation could only be done because Piet Petu had a basic knowledge of ethnographic methods, and since he was also from an original tribe and had experienced various traditional rituals since he was a child.

12Nggalu, Eka Putra. Membayangkan Kembali Bikon Blewut in Laune April 29, 2022. Accessed online on July 1, 2022. https://laune.id/membayangkan-kembali-bikon-blewut/

13Hikon, Jefron (ed.). Napak Tilas Berdirinya Museum Bikon-Blewut in Museumbikonblewut Maret 03, 2021. Accessed online on July 1, 2022. https://museumbikonblewut.blogspot.com/2021/03/napak-tilas-berdirinya-museum-bikon.html

15Ngo, Defri. Re-Imagine Bikon Blewut; Efforts to Live in Biennale Jogja September 30, 2021. Accessed online on July 1, 2022. https://biennalejogja.org/2021/en/re-imagine-bikon-blewut-efforts-to-live

Along with Piet Petu’s passing on November 24, 2001, the Bikon Blewut Museum lost its most visionary thinker. Currently, although it still stands firmly in the courtyard of the Catholic high school, the appreciation towards this museum has decreased considerably. However, recently, the museum has attracted a group of young artists, an art collective known as Komunitas KAHE, who carry out artistic interventions in it by involving the surrounding community.15 They aim to restore Piet Petu’s mission, along with the official inauguration of the Bikon Blewut Museum, so that the museum can pass on the wealth of cultural heritage of Flores, and become a source of knowledge for the younger generation.

In particular, I also want to acclaim the progressive artistic approach that broke down the museum walls, as Arnold Clemens Ap and Piet Petu, SVD accomplished. They indirectly practiced the promoting of what James Clifford calls a museum as a contact zone, wherein the institutional structure and organization of their collections become a set of tools for imagining historical, political, and moral relations, both for the visitors and the community being represented.16

16Clifford, J.. ‘Museums as contact zones‘ in Routes: Travel and Transformation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. 1997.

1 Munandar, Agus Aris, et al. Sejarah Permuseuman di Indonesia. Jakarta: Direktorat Permuseuman, 2011. pp.14-15.

2 Kusuma, Erwien. Kuasa Kuratorial dalam Tata Pamer Museum, Academia. Accessed online on May 13, 2022. pp. 3. https://www.academia.edu/41800140/Kuasa_Kuratorial_dalam_Tata_Pamer_Museum

4 Susantio, Djulianto. Moh. Amir Sutaarga, Kamus Hidup Permuseuman in Majalah Museografia Vol. VI, No. 9 – Juli 2012. Jakarta: Direktorat Pelestarian Cagar Budaya dan Permuseuman. 2012. Accessed online on May 13, 2022. https://museumku.wordpress.com/2012/09/14/moh-amir-sutaarga-kamus-hidup-permuseuman/

5 Flores, Patrick D.. Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Museum. 2008.

6 Hujatnikajennong, Agung. Kurasi dan Kuasa: Kekuratoran dalam Medan Seni Rupa Kontemporer di Indonesia. Jakarta: Marjin Kiri. 2015.

7 Supangkat, Jim. Kemunculan Kerja Kurasi di Indonesia pada 1990 dan Latar Belakangnya. Proceedings of the Imagined Curatorial symposium at Bandung Institute of Technology. August 8-10, 2018.

8 Stolley, Richard B.. An Anguished Search for Signs of A Missing Son in LIFE Magazine December 1, 1961. Accessed online on May 13, 2022. pp. 40-46. https://books.google.co.id/books?id=AVQEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

9 Goo, Andreas (ed.). Grup Mambesak: simbol kebangkitan kebudayaan orang Papua Proto. Jayapura: Uncen Press dan Lembaga Studi Meeologi Press. 2019.

11 Ibrahim, Raka. Arnold Ap: Papua’s lost cultural crusader gets long-delayed recognition in Jakarta Post September 2, 2021. Accessed online on May 13, 2022. https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2021/09/02/arnold-ap-papuas-lost-cultural-crusader-gets-long-delayed-recognition.html

12 Nggalu, Eka Putra. Membayangkan Kembali Bikon Blewut in Laune April 29, 2022. Accessed online on July 1, 2022. https://laune.id/membayangkan-kembali-bikon-blewut/

13 Hikon, Jefron (ed.). Napak Tilas Berdirinya Museum Bikon-Blewut in Museumbikonblewut Maret 03, 2021. Accessed online on July 1, 2022. https://museumbikonblewut.blogspot.com/2021/03/napak-tilas-berdirinya-museum-bikon.html

15 Ngo, Defri. Re-Imagine Bikon Blewut; Efforts to Live in Biennale Jogja September 30, 2021. Accessed online on July 1, 2022. https://biennalejogja.org/2021/en/re-imagine-bikon-blewut-efforts-to-live

16 Clifford, J.. ‘Museums as contact zones’ in Routes: Travel and Transformation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. 1997.

Share

Author

Sponsor