Grassroots Curating in Asia

When I joined the Beijing LGBT Center in 2007, I was still a student in the Philosophy Department at Nanjing University. Prior to that, I had attended a summer camp for gay and lesbian youth in Beijing, which I had discovered through the BBS board, The Same Sky, at Nanjing University. I went to an offline gathering of The Same Sky once, where a group of brothers crowded into a cafe, and there was silence except for the organizer’s voice. In contrast, there was a lively vibe at the summer camp. Many participants attended school in Beijing and were engaged in various arts and cultural activities. Therefore, my first impression of Beijing was that it was an expanded version of my own college queer community: a bigger stage, more gay-friendly, and featuring an exciting art scene. As time has gone by, I now only remember a few significant moments of the camp. The organizers had invited queer activist and filmmaker duo, Shitou and Mingming to be the judges, and everyone created a work using Greek plaster statues for the entrance exam, which were placed in a bazaar-like open field. I painted one of the statue’s eyes red, as if he were crying, and ironically, it fell over. At the end of the camp, another boy wrapped himself in toilet paper as if he were a suffocating mummy. When I think about it now, although we all looked the hopeful youths, we were all uncertain about the future, and our hearts were strangely filled with bitterness. We were all naïve beautiful souls, Die Schöne Seelen, in Hegelian term.

Upon returning to school for my senior year, I was immediately consumed by concerns about my future work prospects and life after graduation. I recalled how, in our first year, our major professor had often urged us to undertake internships early on, assuring us that they would not let us fail. It wasn’t until I began facing the daunting reality of the job market that I fully grasped his advice—philosophy graduates, in particular, face significant challenges in securing employment. After enduring several unsuccessful job interviews, I learned about the establishment of the Beijing LGBT Center. The center was founded and managed by the same organizers behind the summer camps I had attended, including aizhi.net, Aibai.cn, and tongyulala.org, as well as Gay Spot and Les+ magazines, as these groups were all dedicated to supporting the LGBTQ+ community. I promptly submitted my résumé and was thrilled to receive a positive response shortly thereafter. Years later, Zhao Ke, the editor-in-chief of Gay Spot magazine, reminisced about this event and revealed that I was chosen because they believed I possessed certain artistic qualities—or, at the very least, the ability to enhance the aesthetics of the center’s interior.

I was involved with the Center for about three or four years, during which it navigated numerous challenges since its inception, including issues related to censorship, fundraising, and establishing a clear orientation. The space we occupied was provided by human rights attorney Li Fangping. We therefore shared this office with the China-Dolls Center for Rare Disorders, which supports individuals with rare diseases such as brittle bone disease, and the Beijing Yirenping Center, which advocates for the rights of Hepatitis B patients.1 It was in this environment that I encountered true grassroots idealists committed to societal change through their own efforts. During my time working and living alongside them, I absorbed their aspirations and dreams, though many of their deeper meanings have only become clear to me with the passage of time.

The work at the Center was multifaceted: anyone with an idea would start a pilot, gather participants online, and observe how it developed. Most activities were spontaneous, like film gatherings that lasted the longest. I was involved in initiatives such as the Shining Jazzy Chorus, co-founded with Ling Yu of the Aizhixing Institute of Health Education, which focuses on HIV/AIDS activism. This choir, which started as a male-only ensemble with fewer than ten members, highlighted an early challenge for the Center, with lower participation from lesbians and transgender individuals. Over a decade, the choir transformed into a sexuality-inclusive ensemble of about two hundred members, regularly performing to full houses at public events, surpassing the lifespan of the Center itself. During my tenure at the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, I invited them to perform at the museum, and in 2018, I had the honor of being a leading vocalist at their 10th-anniversary performance. However, as the social environment shifted, the choir, renamed the Beijing Queer Chorus, faced increasing violence and harassment, which ultimately prohibited them from performing in public theaters.

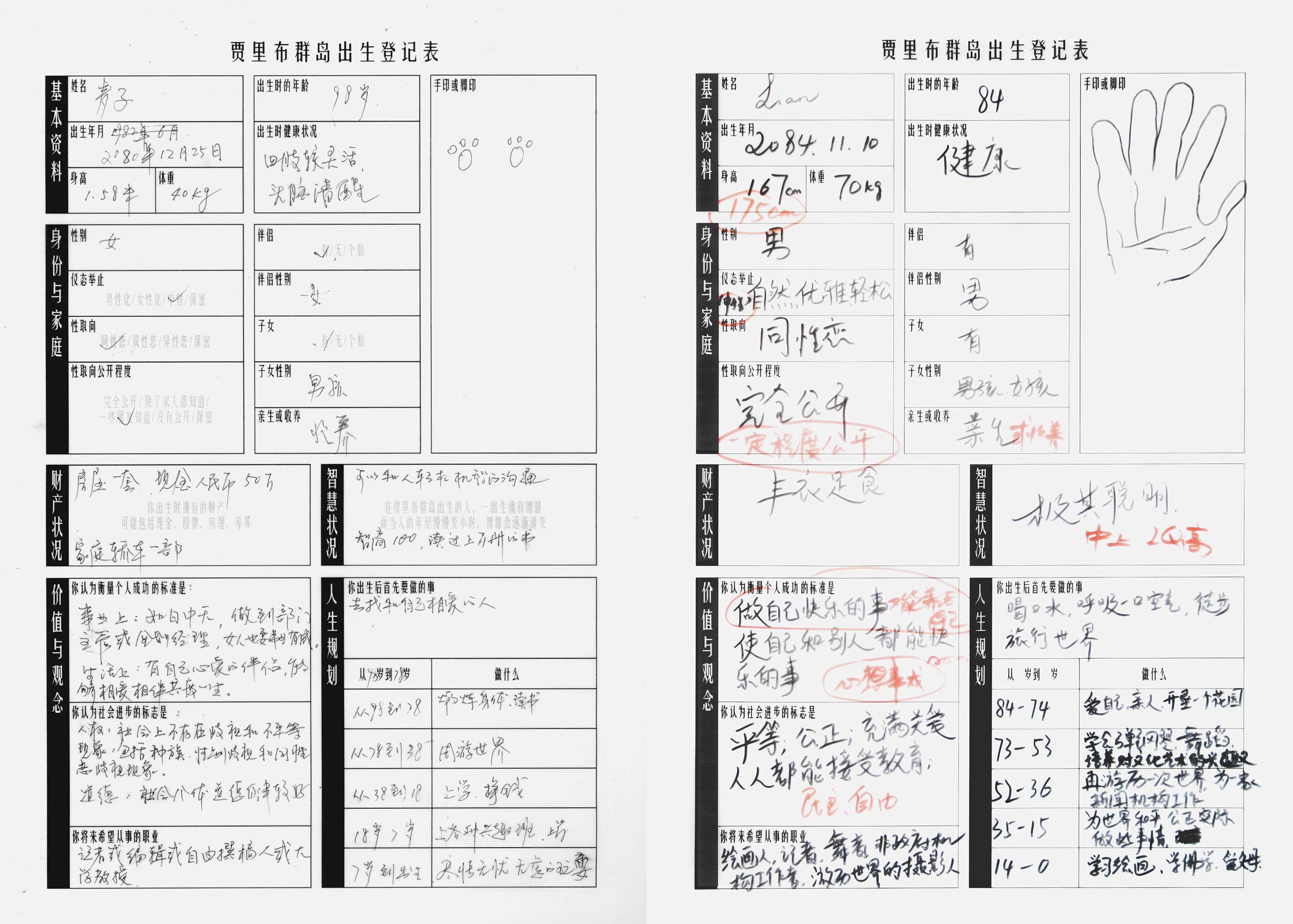

Working at the Center introduced me to many artists, and I owe a special thanks to Zheng Bo. In 2008, Zheng had recently returned to Beijing from the States as a Ph.D. student at the University of Rochester, and he approached us to film his work Karibu Islands at the Center. This project imagined an archipelago where inhabitants are born as old men and die as babies, with the islanders portrayed by gay men recruited from the center. It was a time when gender diversity witnessing rapid transition, and many participants expressed anxiety about their families and futures. Zheng Bo, a passionate individual, noticed my interest in contemporary art and generously connected me with the cultural community, often organizing queer gatherings in the Sanlitun area.

“Difference–Gender”

I deeply reminisce about the vibrant energy that permeated the air before and after 2010, a period marked by the privilege of curating Difference–Gender: The First Chinese Art Exhibit on Gender Diversity in Beijing during the summer of 2009.2 As I recall, the venue at Citizen Film Studio, a gray brick studio in Songzhuang, was graciously lent to our organizing team free of charge through an introduction by Xiaogang Wei, founder of the online program Queer Comrades. At that time, contemporary art had gone through its initial flourishing, yet the voices of the Chinese queer community remained largely unheard in the art world. The exhibition featured artists who were friends from the community and others recruited online, many of whom have since fallen out of touch. Although the exhibition faced censorship, the atmosphere was relatively permissive compared to earlier times, when gender-themed art exhibitions were often shut down before opening. I can only recall one of Ren Hang’s works was removed—a provocative piece depicting the lower half of a person soaking in a bathtub, with their private parts obscured by a fish that appeared to be performing oral sex.

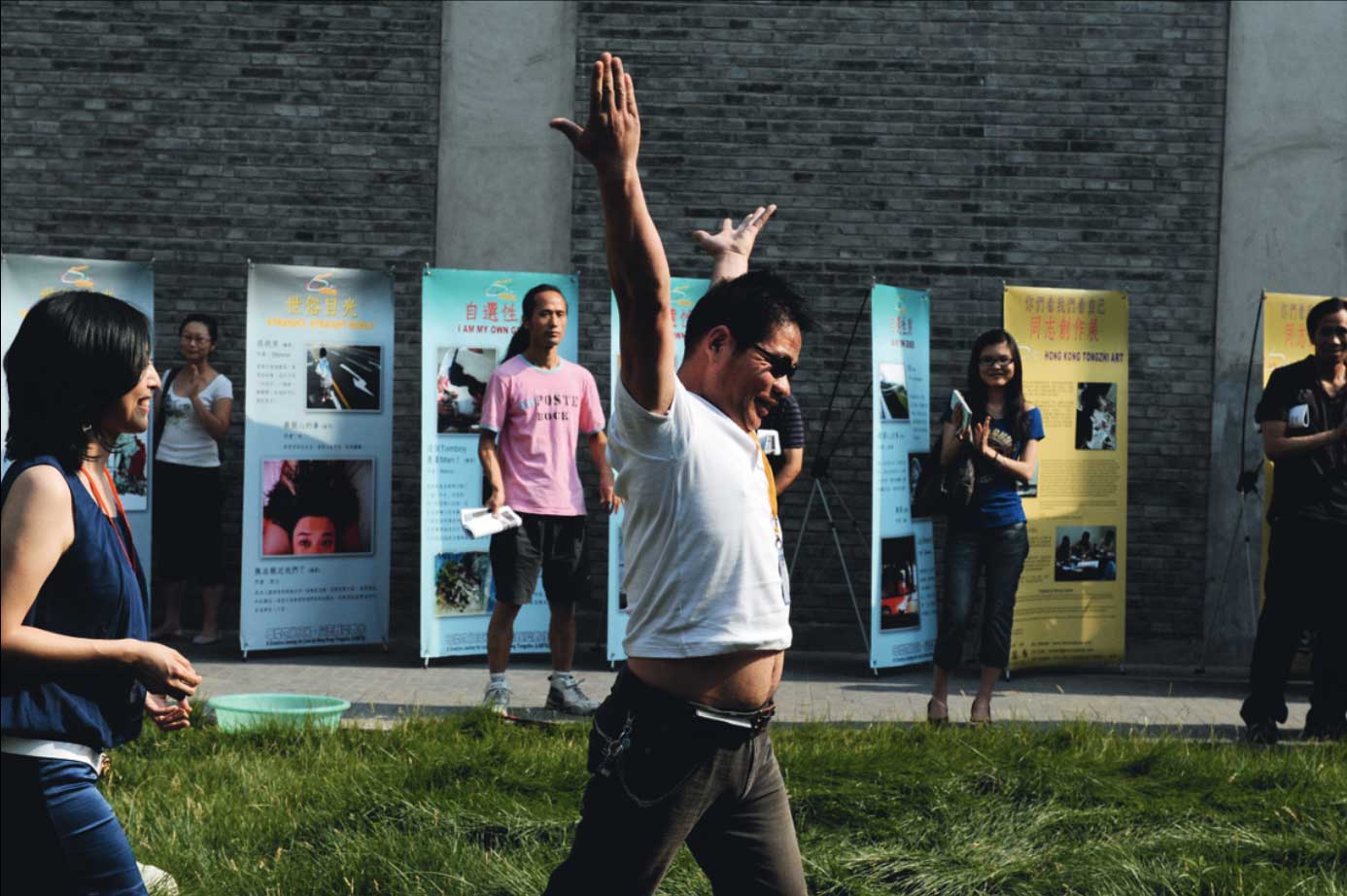

Zheng Bo later remarked that the most memorable aspect of the exhibition for him was the work of Xiyadie and his intricate paper cutouts. At the exhibition’s opening, the host called upon Xiyadie to speak. He mentioned feeling as if he could fly. Caught in the moment, he raised both arms in a gesture of flight, and exposed his belly. His entire presence seemed to glow with light. The exhibition’s subtitle, Art of Gender Diversity, emphasized sexual minorities beyond the traditional binary gender paradigm. However, we weren’t able to comprehensively address issues related to class, region, age, and other factors. For those who are especially vulnerable within an already marginalized group, expressing themselves is particularly challenging.

Xiyadie’s entry into the group exhibition was fortuitous. While visiting Dongdan Park, a popular cruising spot, he noticed volunteers distributing the Gay Spot magazine, which advertised the exhibition’s call for submissions. Intrigued, he contacted the magazine, and the editor-in-chief asked if I could meet the artist and review his work. When Xiyadie arrived, he presented us with his extraordinary paper cuts—narrative, rhapsodic, and folkloric pieces that vividly expressed his ecstasy and lamentation over sex, impermanent fate, repression, and freedom. Despite our vastly different life paths, I felt a profound connection between his art and my own experiences.

It was only after seeing his work that I learned about his life experiences: born and raised in rural Shaanxi, China, Xiyadie was a father of two children, one of whom had a disability that necessitated his working tirelessly to support his family. It was during this challenging period that he began to understand his own sexuality, leading him to move to Beijing in 1998. There, he experienced a series of unforgettable love affairs and relationships. He was in his forties when I met him. To raise funds for his seriously ill son, we later organized his first solo exhibition, The Absolute Beauty of Submission, at the LGBT Center in 2010. In March 2024, we reunited at the opening of his solo exhibition at Blindspot Gallery in Hong Kong, where we shared a heartfelt meal. He lamented that in his life, he had many plans, but none had kept up with the changes. By then, his son had already left him. Despite these challenges, we celebrated his successes, including his exhibition in Hong Kong and his upcoming participation in the central pavilion of Venice Biennale.

The Reproduction of Ideology

In 2009, I attended the final exhibition where Gu Dexin announced his retirement from his art career, 2009-05-02, at Galleria Continua. The exhibition walls were adorned with big-character-poster-style fonts bearing stark declarations: “WE KILLED HUMANS WE KILLED MEN WE KILLED WOMEN WE KILLED THE OLD WE KILLED THE KIDS WE ATE HUMANS WE ATE HUMAN HEARTS…” On a high platform, the phrase “We can go to heaven” was repeated twice. Monitors suspended near the ceiling monotonously displayed videos of the blue sky. Gu’s work unveiled the greed and ruthlessness inherent in human nature, alongside a desire to cleanse oneself of sin by relying on a higher being. He used the subject “we” without distinguishing himself from the collective, understanding that a superior moral stance can be condescending, yet consciously refraining from adopting a morally judgmental position. His works remain true to human nature, while simultaneously conveying profound compassion and care. I consider his works to be anti-establishment and non-ideological.

China’s trajectory towards economic neoliberalism, as part of its reform and opening-door policy, represents a shift towards secularization concomitant with modernity. Prior to this, socialist China had been systematically cultivating a specific teleology in a broad sense of spirituality, by which the art of the Cultural Revolution can best be seen as representing the mainstream. In the post-Cultural Revolution era, movements like the The Stars Art Group and the ’85 New Wave emerged in opposition, whether through the appropriation of pop art or the use of folk and religious visual elements, showcasing their rebellious spirit against Cultural Revolution art and its ideological apparatus. The arts of the Cultural Revolution aimed to create representations representative of a modern nation-state. In shaping ideological portraits through artistic means, “subversive voices” shall become a new aesthetic. However, it is crucial to recognize that any aesthetic inherently mirrors an ideology. Even a marginalized ideology, once institutionalized, tends to develop a certain expansion toward the center.

In “Ideology and the Ideological State Apparatuses,” Louis Althusser puts forth three resonating points, which I will quote at length:

1. All ideological State apparatuses, whatever they are, contribute to the same result: the reproduction of the relations of production, i.e. of capitalist relations of exploitation. 2. Each of them contributes towards this single result in the way proper to it. The political apparatus by subjecting individuals to the political State ideology, the “indirect” (parliamentary) or “direct” (plebiscitary or fascist) “democratic” ideology. The communications apparatus by cramming every “citizen” with daily doses of nationalism, chauvinism, liberalism, moralism, etc, by means of the press, the radio and television. The same goes for the cultural apparatus (the role of sport in chauvinism is of the first importance), etc. […] 3. This concert is dominated by a single score, occasionally disturbed by contradictions (those of the remnants of former ruling classes, those of the proletarians and their organizations): the score of the Ideology of the current ruling class which integrates into its music the great themes […]3

The interplay between direct ideological control and the ideological apparatuses—such as religion, culture, and family—presents a nuanced landscape for the production and reproduction of ideology. These apparatuses, particularly at the familial and educational levels, often operate under a guise of neutrality, making their influence more insidious. At 21, when I joined the LGBT Center, I leveraged popular college network channels to recruit participants who shared similar age, educational backgrounds, and social contexts. The college demographic tended to espouse ideals of purity and enduring love, often critiquing the perceived chaos of contemporary sexual relations and subtly disapproving of married queers. As the center grew, attracting a diverse range of social groups, ideological clashes became inevitable. The older, more grassroots members of the gay community bring a depth of life experience to our discussions. They engage in lively debates, offering sharp, vulgar yet insightful comments that they playfully aim at us younger ones. They tease us about how, even though our head might seem in the clouds, our dick speak louder than words. This banter allows us to mingle without feeling patronized. In discussions with Zheng Bo about the original Difference–Gender exhibition, he seemed to express similar observation: the participating artists were generally younger and better educated, with the notable exception of Xiyadie. His paper-cutting art and involvement in the exhibition underscored the message that “being gay is not simply a young people’s affair.”4 This dynamic reflected broader social realities in China around 2009. Post-80s students harbored dreams of a middle-class future, aligning themselves with mainstream identities while grappling with moral complexities.

Conversely, others embraced their imperfections, creating meaningful personal frameworks outside societal norms. While I support art that explores gender identity, I am cautious of the conceptual systems underpinning such expressions. As the cultural apparatus inevitably lends paths to ideological reproduction upon the gender matrix, my focus gradually shifted, leading me to resign from the Beijing LGBT Center in 2011 to pursue my passion for contemporary art. My departure likely disrupted the community, as I was the sole employee at the time, but it marked a necessary transition in my personal and professional journey.

In my beliefs, I am not averse to the idea of the art of self-interest, that is, the artist expressing personal interests from a socially disinterested position. However, I am suspicious of any art that intends to create a collective image, e.g., one that successfully represents a national ideology, which is tempting but does not deliver the essential meaning for my work. In my early twenties, I was limited in my knowledge of art, limited in my understanding of the significance of socially relevant work, and stubborn and naïve. Since the organizations that supported the LGBTQ Center were all NGOs, there was inevitably a divergence in thinking—as I mentioned above, I was too abstract and did not offer artistic solutions in terms of quick-impact social change events. Such proposals, in my opinion, also violate the principles of art in my philosophical perspective. If I had another chance, I would have made a clear distinction between the two, accounted for them, and utilized my power in a mature and flexible way. In any case, it is humans that I value, rather than any “ism,” prescribed by any existing ideology.

1 Examining the parallels between different activist groups is worthwhile; notably, the Yirenping Center also advocates their goals through performance art. See: Lu Jun, “The Yirenping Experience: Looking Back and Pushing Forward” in Made in China Journal, July 15, 2021. https://madeinchinajournal.com/2021/07/15/the-yirenping-experience-looking-back-and-pushing-forward

2 The year 2009 is named as “the Year of Gay” by China Daily, December 28, 2009. http://www.china.org.cn/china/2009-12/28/content_19142822_2.htm. Accessed June, 4, 2024.

3 Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (New York: Monthly Review: 1971) 154.

4 Yang Huang and Zheng Bo, “Discussing the Works of Xi Ya Die and Yan Xing,” The Body at Stake: Experiments in Chinese Contemporary Art and Theatre. Jörg Huber and Zhao Chuan (eds.) (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013) 231-244.

Share

Author

Yang Zi is a Beijing-based independent curator. He worked at the Beijing LGBT Center (2007–11) and served as an editor at LEAP Magazine (2012–14). He also held positions at UCCA Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, as executive editor (2015–18) and later as curator and head of Public Programs (2018–19). His recent curated institutional exhibitions include Duan Jianwei: The Departure to Xindian at Long Museum, Westbund, Shanghai, 2023; Nián Nián: The Power and Agency of Animal Forms at Deji Art Museum, Nanjing, 2023; White Holes: The Mysteries and Modern Perceptions of Oracle Bone Script at 798 Cube Art Museum, Beijing, 2023; and Two Sides of One Coin: Reflections and Transformations at Taikang Art Museum, Beijing, 2024. He was a finalist for the Hyundai Blue Prize in 2017, a preliminary jury for the Huayu Youth Award in 2019 and 2021, and the recipient of the inaugural Sigg Fellowship for Chinese Art Research in 2020.