In a recent essay on the 2024 Diriyah Biennale that extends to diagonalizing the general plight of large-scale international exhibitions, Singaporean artist and writer Ho Rui An contrasted the gradual demise of biennales in Europe with the resurgence of the exhibition format in the Global South, despite privileging its archetypal form as a large-scale exhibitionary showcase. A key moment in this shift was documenta fifteen (2022), where Indonesian artistic director ruangrupa promoted grassroots approaches as a critique of the large-scale exhibition model.1 While the main criticism at the time centered on allegations of antisemitism, several critical examinations of ruangrupa’s grassroots/exhibitionary dilemma intersect with critics’ desire to reference critical glossaries beyond the confines of the Global North. Kassel-based curator and critic Mi You observed that the anti-exhibitionary experiment, initiated from the “backend” of the institution, still stumbled over structural hurdles, thereby reducing the presentation to a series of “small gestures.” She further explores the long history of community art in Indonesia, highlighting how ruangrupa’s generation has intertwined their activism with populism within this contextualized historiography. Another key issue she highlighted, often underemphasized in criticism from the Global North, is that financial support from foundations like Ford in the Global South has led to the uncritical assimilation of grassroots art collectives and social work organizations.2 Similarly interested in reflecting practices beyond Western parameters, Ho’s analysis focused on one of the key curatorial gestures in documenta fifteen, the “mini-majelis.” This initiative divided participating artists into five mini-legislatures, with regular online meetings to decide on resource distribution and other autonomous initiatives. Although documenta fifteen’s official translation suggests that majelis means a horizontal gathering, Ho highlights its centralized undertone rooted in Arabic etymology. He noted that what began as a non-exhibitionary approach has become bureaucratically demanding, ultimately resembling state mechanisms and failing to reimagine the very nature of statebuilding.

This issue of Curatography invites writers to explore cases that concern the notion of grassroots exhibitionaries within the myriad threads of Asia. Initially, the pairing of grassroots and exhibitionary may seem unnatural: this will be the case If we view exhibitionary as rooted in Western modernity. For instance, Tony Bennett’s concept of the “exhibitionary complex” highlights how museums, alongside the rise of punitive state institutions, were established to publicly present artifacts and cultivate the European middle class. In the academic historiography of curating, the concepts of grassroots and exhibitionary have been framed as two antithetical concepts attempting to converge on their own terms: either through the “curatorial turn” of the Anglophone protest cultures, or the “social turn” in academic curating practices.3 Compared to the extensive literature of above trends, I’ve found most small grassroots exhibition initiatives I have visited in Asian cities remain largely out of place in that context. For instance, the Chung Li-ho Museum in Kaohsiung, Taiwan (1983–) and the Picun Museum of Migrant Worker Culture and Art in Beijing (2008–2023) stand out as notable examples. Located in Meinong, a traditional Hakka farming neighborhood, the Chung Li-ho Museum was established to commemorate the Hakka novelist Chung Li-ho and to continue his legacy of peasant-themed realism. The museum houses collections of Chung’s manuscripts, along with donated manuscripts and paintings by other radical literati from his era. With the rural economy facing challenges from globalization in the 90s, and under the directorship of the late writer Chung T’ieh-min, son of Chung Li-ho, the museum evolved into a key node for peasant protests and environmental movements among the agricultural communities. By hosting regular literary events and fostering solidarity among various activist groups, the museum remained a hub for social movements until the 2010s when local excavation activities came to a halt. The Picun Museum, on the other hand, was situated in a prominent area for migrant workers on Beijing’s outskirts, addressing labor issues that arose after the neoliberal reforms dismantled China’s state enterprises, transforming workers into isolated units. Upholding Maoist rhetoric in its critique of neoliberal enterprises, the museum employed exhibition methods typical of the socialist era, including an open call survey that collected exhibits such as workers’ belongings, legal documents, and documentation of bodily scars that best represented their struggle against private capital in postsocialism. Alongside the museum were the Picun Literature Group, a writing workshop for migrant workers, and the Tongxin Experimental Primary School for the second generation of these undocumented migrant workers. Another relevant case is the Conflictorium (2013–), a community museum in Mirzapur, Ahmedabad, northwest India.4 The neighborhood, with its mix of religions, went through significant riots in the 1990s, resulting in lingering traumas within the community. Initially conceived by artist Avni Sethi and with YSK Prerana taking over as director last year, the museum is dedicated to mediating conflicts through artistic means. It features sections that chronicle Gujarat’s violent history, highlight social disputes using interactive and sensory mediums, and explore nation-building ideologies, while offering unique installations like the “Sorry Tree” and intimate sound exhibits, as well as spaces for temporary exhibitions, workshops, and residencies.

The three cases are similar in that their emergence and methods are deeply rooted in their geo-historical specificity, engaging local audiences across a wide age range while maintaining a radical agenda. While these models, which delicately balance exhibitionary practices with radical politics, may prove challenging to replicate as curatorial methodologies, we also observe how biennials often integrate such grassroots exhibition models. Rather than assimilating their methods outright, they achieve this by fostering collaborations between artists and community museums on specific projects: such as Maria Thereza Alves’ collaboration with the Museo Comunitario del Valle de Xico at documenta 13 (The Return of a Lake, 2012), and Yin Aiwen’s collaboration with the Dinghaiqiao Mutual Aid Society in Shanghai on the 2022 Shanghai Biennale (Liquid Dependencies, 2022).

In an effort to further the lineage of grassroots exhibitionaries, this issue invites three practicing curators to apply these analytical frameworks to different case studies: Anushka Rajendran, based in New Delhi; Taiwan-based Wu Sih-Fong; and Yang Zi from Beijing. They will explore cases from their specific Asian contexts. Their contributions aim to disrupt and expand the implications of grassroots exhibitionaries, potentially extending beyond my earlier circumscription, with the hope of enriching the analytical tools needed to draw complex geometries among parameters beyond typical academic curatorial framing.

Anushka Rajendran: “Musing The Artistic Alchemy: Reflections on the Artist-Curator Model of the Kochi Muziris Biennale”

With a topical focus on the institutional characterization of the idiosyncratic Kochi-Muziris Biennale, an Indian artist-run exhibition platform since 2012, New Delhi-based curator Anushka Rajendran situates it within the broader history of curating in South Asia. She highlights its unorthodox artist-curator model among peer international exhibition frameworks. By examining the anti-elitist exhibition-making gestures by one of the founding directors, also, an artist from Kerala, Bose Krishnamachari dated back to the early 2000s, Rajendran suggests that his “hyper-inclusive” approach to forming group shows has served as a critical counterpoint to the normalized legacy of the auteur-curator. This has prefigured the biennale’s decisive turn away from the nation-based Indian contemporary art survey shows popular among the previous generation.

While one may not entirely consider an international exhibition a grassroots institution, by inviting only artists to curate respective episodes of the the biennale, it has effectively negated certain uncritical implications of professionalism in curating, thus offering the Indian art scene an alternative connectivity to Global South art communities.

This piece is timely as the biennale currently faces existential uncertainty, with no details yet announced for the forthcoming edition set to launch later this year. Rajendran analyzes its significant challenges by scrutinizing the ways artist-curators narrate the geo-mythical imagination of Muziris from its inaugural version. Initially serving as a strategic departure from the imagery of typical “national” art exhibitions, this symbol of precolonial internationalism has gradually come to face its limits by aligning with an instrumentalized version of decolonial rhetoric typically promoted by the nation-state. While its non-professional administrative systems remain unresolved, the future of the biennale is becoming more precarious with the recent acquisition of its main venue by the Indian Coast Guard, signaling a need for restructuring and reinvention.

Wu Sih-Fong: “Strolling and Catching a Show: the Performance Walks of Macau-Based Performing Art Group Step Out”

Hualien-based theater critic Wu Sih-Fong examined the 20-year practice of performance walks by the Macau group Step Out (2001–), focusing on the city’s urbanization and erasure of collective memory. These site-specific performances challenge traditional theater by activating archives and oral histories, providing sensory experiences of the city’s historical changes, and incorporating exhibition elements to prompt audiences to reassess urban spaces. A notable example is The Rise and Fall of the Long Tin Opera Troupe (2010), which reenacts the 1847 story of a Portuguese general whose ruthless development policies led to his assassination by local villagers. For me, this piece holds autobiographical significance for the city that dreams of ever-expanding investments, as the performance walk took place on a street still bearing the general’s name. There’s also a kind of autobiography in Step Out: the performance walk seemed to resurrect the titular village opera troupe to tell their own story to contemporary citizens, reflecting Step Out’s identification with this historical grassroots theater group.

Reviewing literature on site-specific theater in Macau since the 90s reveals that while most archival sources use the term “site-specific theater” in English, the Chinese term actually suggests Richard Schechner’s environmental theater, likely because it is less counterintuitive. It’s not surprising, then, that some readers see a connection between performance walks and curatorial practices. Wu’s analysis culminates in his co-curated project with Step Out, Act For the Sea: Marine Culture Exchange Program (2011). In this project, he examines Step Out’s implicit shift in artistic gestures—what he refers to as “non-performance.” This quality comes from their role in mediating different artists who present projects related to environmental critique during a day-long city walk, where performance is merely one of their curatorial tools, allowing for more space welcoming spontaneity and critical reflection.

As Step Out has developed its artistic language from the ground up in active response to the cultural tapestry of the formerly colonial city, I believe performance walks can also serve as solutions for large-scale exhibitions, balancing exhibitionary elements with critical engagement and reflection. One of the most memorable examples of performance walks, despite its entirely different background, took place at Ghost 2565: Live Without Dead Time (2022), an international exhibition in Bangkok featuring site-specific video and performance art. Koki Tanaka’s commissioned work, Eating an Apple While Lucid Dreaming (2022), reportedly gathered audiences for a nighttime tour around Bangkok. During this tour, a bus transported participants to various sites of past political events, allowing them to take short naps along the way. The bus continued moving throughout the night, creating a seamless journey that symbolized the process of political trauma recovery, blending wakefulness and lucid dreaming.

Yang Zi: “Queers and Art in Precarity: Reflections on NGOs and Curatorial Practices in Beijing”

In this beautifully crafted memoir/autotheory, Beijing-based curator Yang Zi reflects on his debuted curated project, Difference–Gender: The First Chinese Art Exhibit on Gender Diversity while working at a grassroots queer NGO, offering a unique case on the intersection of social work and curatorial methods in 2009. His critical self-analysis is deeply informed by his grassroots queer elder friends, often from rural backgrounds, who provide a resilient understanding of the struggle without formal theoretical training but empirical lived experiences. This vivid insight has been the most characteristic part of his exploration.

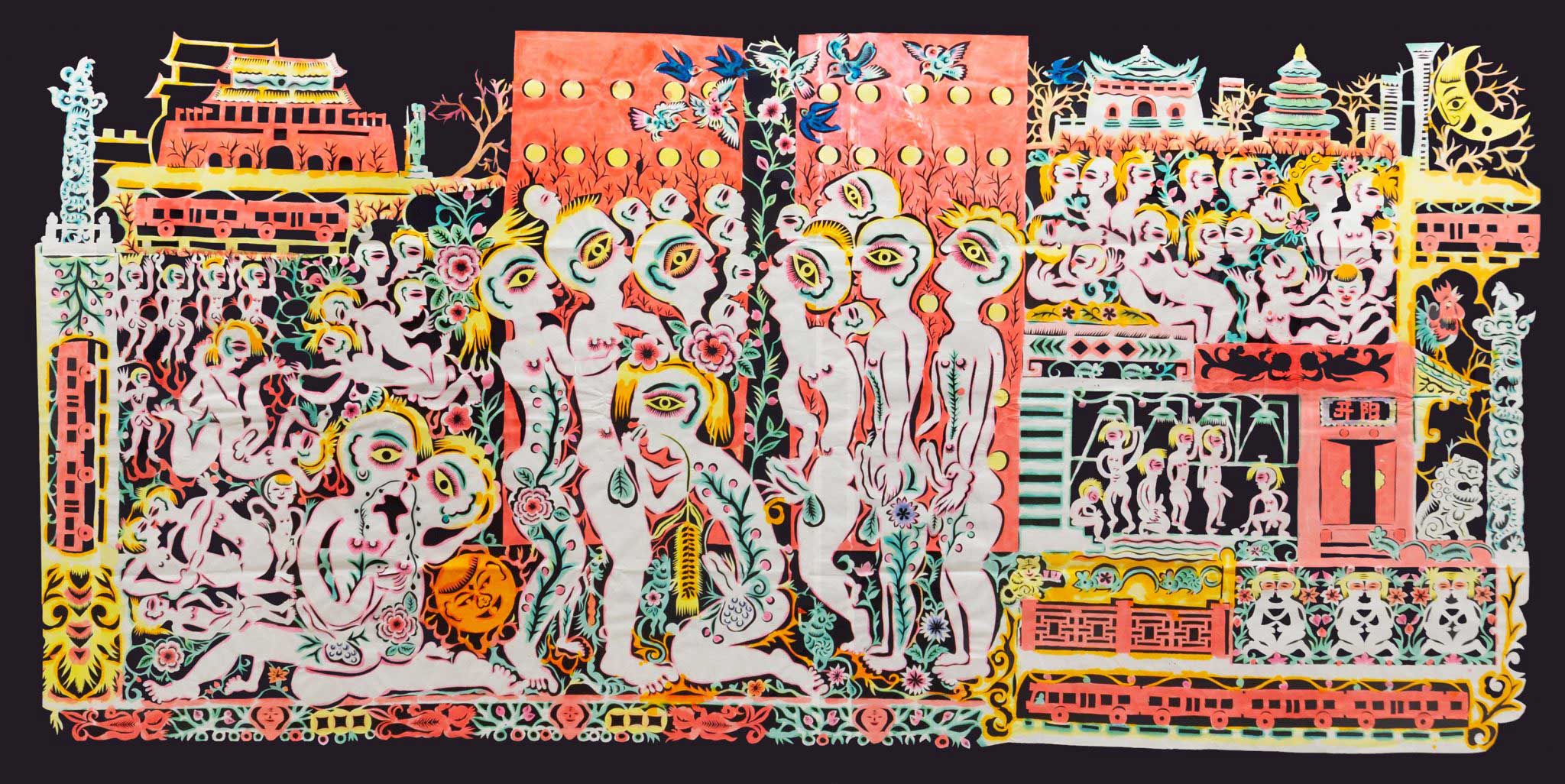

However, given the overall framework of this issue that seeks a complementary synthesis between the grassroots and the exhibitionary, it’s intriguing to explore how Yang’s later curatorial career decisively diverges from his early grassroots exhibition practices—or at least how this critical synthesis might have appeared otherwise. To contemplate this, one may trace from the extension lines of Difference–Gender. One of the participating artists with whom Yang has developed a long-term relationship, Xiyadie, is currently showcasing his personal recollections of the Beijing gay scene through ,Kaiyang (2021), a papercutting epic currently on view at the major theme show of the 2024 Venice Biennale.Titled after a legendary gay sauna at the heart of Beijing, the papercut infuses the yin-yang cosmology from his rural northern Shaanxi upbringing, depicting the abundance of queer desire rampantly flourishing beneath the ultimate symbol of control and surveillance, Tiananmen Square, in the proximity of this underworld haven.

As Yang has characterized in his past conversations with Zheng Bo, another participating artist of the Difference–Gender show, Xiyadie depicts highly personal moments from his life using the highly-stylized medium of Chinese papercutting. The symbolism in his work makes his depiction of the human body and appearance highly direct—you get the sense that nothing is taboo. Yet, this populist art form also manages to connect with the audience, reflecting his social status and economic condition as a middle-aged rural peasant from the home of papercutting, northern Shaanxi. I wonder if Xiyadie’s grassroots exhibitionary approach, for lack of a better term, “transgressive queer populism,” could have been the path Yang might have taken: traditional yet transgressive, not socially-engaging, yet maintaining broader public interest?

1 Ho Rui An, “Biennales and the Exhibitionary in the Global South: Notes from Diriyah,” LEAP Spring/Summer 2024.

2 Mi You, “What Politics? What Aesthetics? Reflections on documenta fifteen,” e-flux, Issue #131 November 2022. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/131/501112/what-politics-what-aesthetics-reflections-on-documenta-fifteen

3 Gavin Grindon, “Curating with Counterpowers: Activist Curating, Museum Protest, and Institutional Liberation,” Social Text Vol. 41, No. 2, June 2023, p.19–44. See also: Laura Raicovich, Culture Strike: Art and Museums in an Age of Protest, London: Verso, 2021.

4 Without personally visiting the museum, I came across this case through Anushka Rajendran, one of the contributors to this volume of Curatography. See: Anushka Rajendran, “The Museum of Conflict: An Alternative Model of Social Engagement,” in Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, Vol. 12, No. 3, September 2016, p. 347–367.

Share

Author

Zian Chen is currently Contributing Editor at Ocula Magazine. His collaborative research and curatorial projects realized with other practitioners have been presented at institutions such as the Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai; the Power Station of Art, Shanghai; the Ming Contemporary Art Museum, Shanghai; the Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou; the Nida Art Colony, Lithuania, and the Bleed Biennial in Naarm Melbourne, among others. He has contributed to exhibition catalogues for artists such as Mark Dion, Arseny Zhilyaev, Elmgreen & Dragset, Wang Tuo, and institutions including the Arrow Factory, Beijing, Liverpool Biennial and Asia Art Biennial, Taichung, among others.