Looking at the current art world, the main locations of art activities are still mainly art museums. In fact, from modern art to contemporary art, so-called “art” has always taken “gaze” as its core, constructed a logical aesthetic framework of “representation” based on authors, works, and viewers, and built an abstract space, usually a museum or a gallery, out of the context of daily life and social context as a field for displaying works of art.

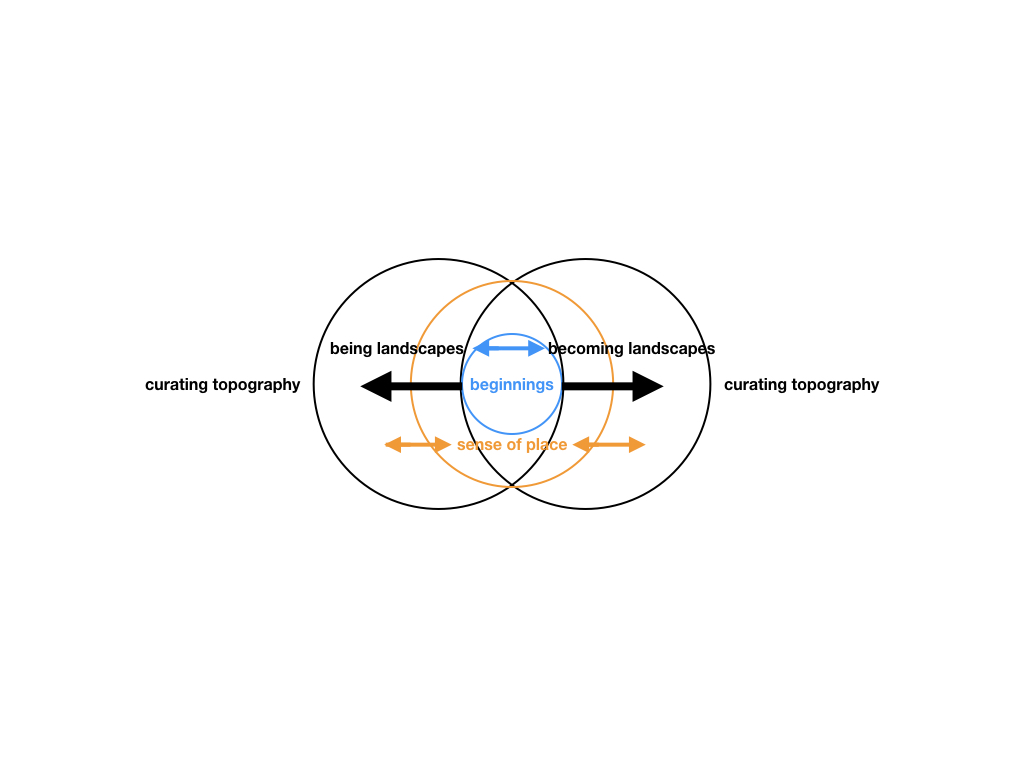

This article presents the curatorial practice with “place” as its core from the perspective of “curating topography”. Curating topography appropriates an aesthetic of cognitive mapping as advocated by Fredric Jameson(Jameson 1991), in an attempt to give individual subjectivity by enhancing a new sense of place in a global system, and to reproduce a new model of representation with complex dialectics in order to position oneself more accurately and enhance the ability to understand the world, and then accurately represent the imaginary relationship between the self and the real world. Cognitive mapping is about positioning ourselves and knowing the world, and “place” is also a way to see, to know, and to understand the world.

If we look at the world as being composed of different places, we can see different things. If self-orientation is based on the starting point of cognitive mapping, then “place” is the anchor of self-identity and worldview. Social practice and knowledge production based on curating topography emphasizes “situation knowledge” that focuses on geographic and cultural specificities, rather than universal knowledge. The purpose is to establish an aesthetic concept connected with life and treat the multitude as active participants rather than passive “gazers”, and regard the place as a becoming art field. From the perspective of curating topography, whether or not there is an art museum or gallery, there are fields for presenting art everywhere. The places in curating topography refer to both physical fields and virtual abstract spaces.

Curating Topography

The emergence of Manet and Impressionism led to the collapse of the collusive structure of academic representatives, opening up the modern aesthetics of “representation” that emphasized “gaze” as the core and the relatively autonomous development of the art field. The development of the entire process included the internal factors of the art field (self-reflection and criticism within the art circle), external factors of social culture (population growth and the expansion of education led to the emergence of bohemian lifestyles that demand pure art), and their interrelationships (Bourdieu, 1993: 113-115). This new aesthetics and artistic autonomy, although allowing artists to refute and reject external requirements and to follow the principles and norms of the art field itself, thus marking autonomy, has also made the art field more and more closed (Bourdieu, 1993: 266). At the same time, the process of this art field towards autonomy must rely on all art participants to share common aesthetic perceptions, tendencies, and habits and must continue to promote and reproduce through education, visiting art galleries, and other activities. Among them, the aesthetic perception ability includes a decoding process (Bourdieu 1993: 226-227). Therefore, this so-called autonomous art field is actually only open to those who are capable of artistic perception, and excludes those who do not have this ability (Bourdieu 1993: 236-237).

The exhibition is the special place where such momentary groupings may occur, governed as they are by differing principles. And depending on the degree of participation required of the onlooker by the artist, along with the nature of the works and the models of sociability proposed and represented, and exhibition will give rise to a specific “arena of exchange”. And this “arena of exchange,” must judged on the basis of aesthetic criteria, in other words, by analyzing the coherence of its form, and then the symbolic value of the “world” it suggests to us, and of the image of human relations reflected by it. Within this social interstice, the artist must assume the symbolic models he shows. All representation (though contemporary art models more than it represents, and fits into the social fabric more than it draws inspiration therefrom) refers to values that can be transposed into the society. As a human activity based on commerce, art is at once the object and the subject of an ethic. And this all the more so because, unlike other activities, its sole function is to be exposed to this commerce. Art is a state of encounter. ( Bourriau, 2002: 17-18)

Marco Casagrade, ‘Oystermen’, “Floating Islands”, curated by Sandy Hsiu-chih Lo,Kinmen, Taiwan, 2013. A public environmental artwork, located on a tidal shore along a tidal road connecting Great Kinmen to the little island towards Xiamen. This area is a oyster habitat, , and the feet of the sculpture are already covered with oysters. Photo by Hsinying Wu.

These days we are no longer trying to advance by means of conflictual clashes, by way of the invention of new assemblages, possible relations between distinct units, and alliances struck up between different partners. Aesthetic contracts, like social contracts, are abided by for what they are. Nobody nowadays has idea about ushering in the golden age on Earth, and we are readily prepared just to create various forms of modus vivendi permitting fairer social relations, more compact ways of living, and many different combinations of fertile existence. Art, likewise, is no longer seeking to represent Utopias; rather, it is attempting to construct concrete spaces. (Bourriau, 2002: 21)

What is Jacques Rancière’s point view? Since he also rejected the aesthetic logic of “gaze” and “representation”, he proposed the concept of “aesthetic heterotopia”:

En-Man Chang, ‘Milky Way’, 2020 Green Island Human Rights Art Festival “If on the margin, draw a coordinate”, curated by Sandy Hsiu-chih Lo. This work is located in the original guard house, and intends to reconnect the split space-time under political governance between Taiwan, Orchid Island and Green Island. Photo by Chi-wei Pan. 2020 Green Island Human Rights Art Festival “If on the margin, draw a coordinate”: https://www.2020greenislandartfest.info

Based on such a space theory, I agree with Harvey that the most difficult thing is to understand how relationality works in order to explore the morals, ethics, and rights of space through free geography, and then to pursue universal justice. In fact, this is also the positive significance of the analysis of space theory for “curating topography”. In addition, “situated knowledge” is an important reference coordinate for finding a starting point for cognitive mapping. Situated knowledge1 aims to focus on geographic and cultural specificity rather than universality. Cognitive mapping focuses on people’s real situations in the context of multiple materials and cultures; therefore, situational knowledge replaces the so-called “objective” knowledge of decontextualization, degenderization, and de-individualization. The key to “curating topography” is to find the “beginning point” of cognitive mapping, to position itself, and to artistically represent the relationship between the self and the world, as well as the real situations of individuals and collectives. It becomes the recognition of place based on the recognition of space., shaping the open sense of place by giving the place a certain collective memory, cultural scenery, and a sense of belonging. This sense of place also serves as a reference point for the connection between the self and the world to develop a map of relational cognitive mapping, and to think about the issues of environment, history, politics, and aesthetics.

1 My main reference of situated knowledge is Donna Haraway “Situated Knowledges: the Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14(3): 597-599 , 1988.

Gieh-wen Lin, ‘Nation Is Not Home’, 2019 Green Island Human Rights Art Festival “Visiting No.15 Liumagou”, curated by Sandy Hsiu-chih Lo. Touching on the complexity and fragmentation of identity, the work is displayed on three round tables at the original site of the commissary. The combination of the tables and the couplet “Full of Friends; Gathering of Guests” at the entrance construct for visitors a diverse space open to imagination. Photo by Sandy Hsiu-chih Lo. 2019 Green Island Human Rights Art Festival “Visiting No.15 Liumagou”: https://www.visitingno15liumagou.com

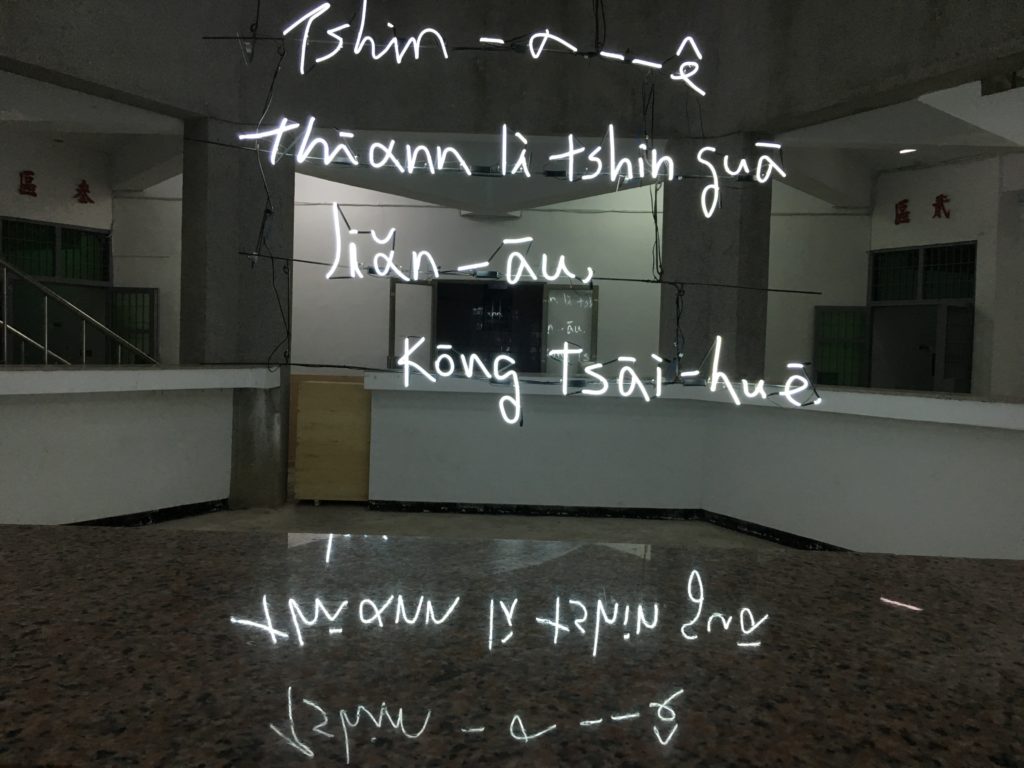

Ding-Yeh Wang, ‘My dear, kiss me and goodbye’, 2020 Green Island Human Rights Art Festival “If on the margin, draw a coordinate”, curated by Sandy Hsiu-chih Lo. This artwork is located by the entrance of the Oasis Villa, in the middle of the Bagua Building. WANG Ding-Yeh has transformed the space, which was originally a place of incarceration that was under surveillance, into one that is lyrical and full of sentiments. Emotive words are shaped with neon light tubes, with the social setting experienced by people when they come to the site redefined during the exhibition period. The artwork wields an unusually gentle gesture that strikes back at the violence of the state machine. Photo by Sandy Hsiu-chih Lo. 2020 Green Island Human Rights Art Festival “If on the margin, draw a coordinate”: https://www.2020greenislandartfest.info

However, many people have never been able to feel a sense of belonging to any place. They are always outsiders and in a placeless state. Or, there are some places called non-places because of anonymity or lack of meaning in the environment in which we live, such as a highway, airport, or shopping mall. Therefore, curating topography not only pays attention to individual differences, but also a brand-new community discourse. It does not seek the integrity of the place that is still lost, but seeks a brand-new place focusing on the cultural imagination of the invisible subjects/unclassifiable multitude. The key is to regard the place as an open art field, a platform for communication and exchange, and a public space that condenses the imagination of the community, a “critical, liberatory, and emancipatory” (Harvey 2009: 161) concept of time and space, and is also a heterotopia between reality and imagination, calling for the production of the relative and relational space, and both dialectically operating in the actual living space and acting on the abstract immaterial cultural space. In this way, “place” has become a constantly changing art field. In the end, curating topography provides a concrete place as a context “to promise a better future world.”

* The first draft of this article was published in the 32nd issue of “Journal of Taipei Fine Art Museum” as “Place: The Becoming Art Field”, and it is also part of the author’s doctoral dissertation “Curating Topography” which is expected to be completed a year later. “Curating Topography” is a curatorial method that the author has been thinking and practicing in recent years.

Baudrillard, Jean. translated by Stuart Kendall, Utopia Deferred: Writings from Utopie(1967-1978), Semiotext(e), 2006.

Bishop, Clair, Artificial Hell: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London and New York: Verso, 2012.Bourdieu, Pierre. The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature. R. Johnson, Ed.Oxford, UK: Polity Press. 1993.

──. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Susan Emanuel trans. Stanford:Stanford University Press, 1996.

Bourriand, Nicolas, translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods with the Patriciation of Mathien Copeland, Relational Aesthetics, Les presses du real, 2002.

Cresswell, Tim. Place: A Short Introduction. Blackwell , 2004.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14(3): 597-599 , 1988.

Harvey, David. Cosmopolitanism and the Geographies of Freedom. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

Massey, Doreen. Space, Place and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

Michel Foucault. “Texts/Contexts of Other Spaces.”Diacritics, 1986.16(1). 22-7.

Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics. Gabriel Rockhill trans. London: Continuum, 2004.

──. The Emancipated Spectator. Gregory Elliott trans. London: Verso, 2009.

____.Philosophy Today, Volume 54, 2010, Recenterings of Continental Philosophy, JacquesRancière, Pages 15-25.

Sharp, Jonne P. Geographies of Postcolonialism: Spaces of Power and Representation, London:Sage, 2009.

Smith, Terry. Art to Come: Histories of Contemporary Art, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. Space and Place: the Perspective of Experience. 8th printing, Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesoda Press, 1977, 2001.

Share

Authors

Sandy Hsiu-chih Lo is an independent curator whose main research areas include urban studies, philosophical construction of space, gender politics, contemporaneity of indigenous art, and situated knowledge. Her current program focuses on curating as a method of social practice, spatial practice, and critical thinking. Curating topography, a curatorial practice method that she has actively used in recent years, uses relative and relational spatial concepts to bring to light different cultural concepts such as myths, legends, history, memories, morals, ethics, desires and rights embedded in the pluralistic dialectic concept of place in order to strengthen political and ethical transformation through the contrast, confrontation, overlap, and juxtaposition in the becoming of place.

Her major curatorial projects include “Di Hwa Sewage Treatment Plant Art Installation: A New Cosmopolitan World”, ”Street Theatre” (awarded as the best curating work and outstanding project by Ministry of Culture, Taipei, 2004-2005), “Pop Pill” (“Shanghai Cool”, Taiwan Section, Doland Museum, Shanghai, 2005), “Border-crossing, A Tale of Two Cities” (Taipei, Shanghai, 2005-2006), “Exorcising Exoticism”(Taipei, 2006), “Poetic Borderline” (“Borderliner”, Taiwan Section, Festival of Contemporary Art Varna, Bulgaria, 2007). She is the co-curator of the related project of 9th Shanghai Biennale “Zhongshan Park Project”(the related project of 9th Shanghai Biennale, Taiwan, China, 2012-2013), “A Revelation from Ponso no Tao”(Orchid Island, Taiwan, 2014), “Taitung Ruin Academy”(Taitung, Taiwan, 2014), “Topography of Mirror Cities” (Taipei, Dhaka, Bangkok, Jakarta, Phnom Penh and Kuala Lumpur, 2015-2021), “2018 Kuandu Biennale Seven Questions for Asia” (2018-2019), “2019 Green Island Human Rights Art Festival Visiting No.15 Liumagou: Memory, Place and Narrative” and “2020 Green Island Human Rights Art Festival If on the Margin, Draw a Coordinate.”