What Is to Be Done in Curating?

Since the invention of photography by French photographer Nicéphore Niépce in 1822, and the subsequent global expansion of photographic practices, the act of taking or making a photograph has served as a ritual for documenting life events and both human and non-human activities. Photographs are commonly perceived and recognized as repositories of memories, active visual mediums that preserve memory. In 20th century cultural and literary discourse, the indexicality of photography further solidified the belief that a photograph is a proof of its captured reality, and confirms that the physical life of a photograph, in its material sense, outlasts human biological life.

However, this anthropocentric belief, shaped by human science, sense, and sensibility, proves otherwise when we delve into the journey of a 19th-20th century photo object of particular interest: the porcelain photo. In the realm of photographic conservation, no photograph—whether a print or an object—is truly everlasting. Over time and under various environmental conditions, photographs exhibit a physical agency that leads to discoloration, deterioration, disappearance (through fading and light-fasting) and disintegration. The physicality of light-sensitive materials like photographs has been a research focus of mine, as it allows for a fundamental examination of different photographic types in relation to their physical, chemical, scientific, historical, political, cultural, and anthropological dimensions.

In the following discussion, I aim at writing afterthoughts on a curatorial endeavour titled Porcelain Photo in Hong Kong: A Mobile Museum (2017). These reflections encompass personal journeys, confessions, supplementary knowledge, and, I hope, new insights into curatorial studies within the Sinophone world and beyond. Before delving into the narrative, I want to clarify some terminology that might cause confusion. I deliberately distinguish between “photograph” and “photography,” as well as “porcelain photo” and “photoceramics,” further articulating their differences, particularly their contextual nuances, below.

The Image Permanence Institute, Rochester, Upstate New York

In the summer of 2015, exactly ten years ago, I first visited the Image Permanence Institute (IPI) in Rochester, New York. Rochester is renowned for the significant contributions of photography pioneer, entrepreneur, and philanthropist George Eastman (1854-1932), founder of the Eastman Kodak Company. Eastman’s innovations led to the manufacture and popularisation of medium-format and 35mm roll film, which profoundly impacted everyday life and has contributed to the rise of amateur photography globally since the mid-20th century. The George Eastman Museum, dedicated to the history, conservation, and practice of photography and moving images, is appropriately named after him, and is located on his former estate. As a photographer keenly interested in the physicality of photographs, I had long wished to experience Eastman’s legacy and that of the Eastman Kodak Company firsthand.

My visit included a five-day period of intensive learning in the “Photographic Process Identification Workshop,” organized by the IPI at the Rochester Institute of Technology, with support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Research scientists Al Carver-Kubik and Ryan Boatright instructed the workshop, alongside fifteen participants from various museums, archives, and research institutes. I am forever grateful for the invaluable knowledge shared by these experts, which significantly shaped the future development of the “Porcelain Photo in Hong Kong” project.

The workshop, as its title suggests, covered most types of photographic prints, focusing on identification and potential conservation strategies. We were immersed in the history, characteristics, and preservation conditions of photographs through lectures, hands-on examination of prints, darkroom practices, and microscopic analysis of the photograph’s physical structures. Personally, this was a profoundly positive learning experience, especially since I lack a formal photographic conservation background. After the workshop, my interest in the history and material culture of photography blossomed exponentially.

I would like to share two illustrative anecdotes from this experience. In a casual Q&A session following a lecture, Al Carver-Kubik was asked for a general overview of the historical development of photograph. Al’s intelligent and succinct reply, delivered with confidence, was that the historical development of photography is about size, speed, and cost-efficiency: photographic processes and production continuously evolved to become larger in size, faster in speed, and cheaper to produce (emphasis mine). Al’s insight was impactful and, in my view, incredibly accessible and applicable.

The second anecdote is particularly relevant to the scope of this essay. My personal interest in researching the technical know-how and cultural histories of porcelain photos was not piqued before the research trip to Rochester. I knew what they were: a photographic image (more precisely, a photo object) usually in grayscale, “printed” on a porcelain surface (which is vitrified). This type of photograph also served as the sole and cherished memory of my late grandfather, whom I had never met.

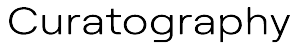

I never had the chance to know my paternal grandfather, a young father of four, since he had passed away over 60 years ago in a car accident in Hong Kong, long before I was conceived. My beloved late grandmother devoted her entire life to caring for the household. I like to imagine their relationship was always loving and mutually respectful. The small ancestral shrine housing my late grandfather in my grandparents’ social housing apartment was always meticulously kept, adorned with blossoming flowers, seasonal fruits, and delicacies. As the eldest grandson in a patriarchal family, I had the privilege of offering burning incense at the ancestral shrine: three sticks at a time, twice a day. Like most families of Canton origin in Hong Kong, the ancestral shrine is a red box resembling a proscenium stage, illuminated by red light, with one or more ancestral portraits at its center, and offerings like incense or food placed at the “apron.” Ancestral portraits are commonly made from a handheld porcelain photo, a framed photograph, or a framed or mounted gongbi photogenic drawing of the ancestor. I always worshipped my late grandfather’s porcelain photo, as it was through this object that I registered the idea of ancestry, family, and patriarchy. This photo object was my first and only impression of my late grandfather, and my first encounter with what a common household porcelain photo looked like.

Returning to the classroom laboratory at the IPI in Rochester, as the class examined and learned about different types of photographs, I couldn’t help but think about my late grandfather’s ancestral portrait—a high-contrast, monochrome, shiny photo object that seemed excluded from the workshop’s discussion. Naively, I jumped to the quick conclusion that porcelain photos might be an exclusively Chinese artifact. It was easy and comforting to think within that narrow scope. On another casual occasion, I asked a fellow classmate if they knew about porcelain photos. Al interjected, clarifying that it’s a photo object named photoceramics in the Euro-American context, and sometimes categorized as “miscellaneous” in collections and archives. Rightly so. This clarification was precisely what I needed: a global perspective on porcelain photos, understanding it as “photoceramics” in the West and “porcelain photo” in relation to my own culture’s practices.

I cannot overemphasize the importance of starting with the correct terminology for primary research in arts and humanities, or any scholarly endeavour. While this idea may seem un-thought-provoking, the volume of research and publications that expend considerable effort arguing and debating terminologies can be overwhelmingly burdensome. Now, I had two sets of terminology to work with: “photoceramics” and “porcelain photo,” each subject to culturally specific expressions and contexts. This distinction became very clear to me.

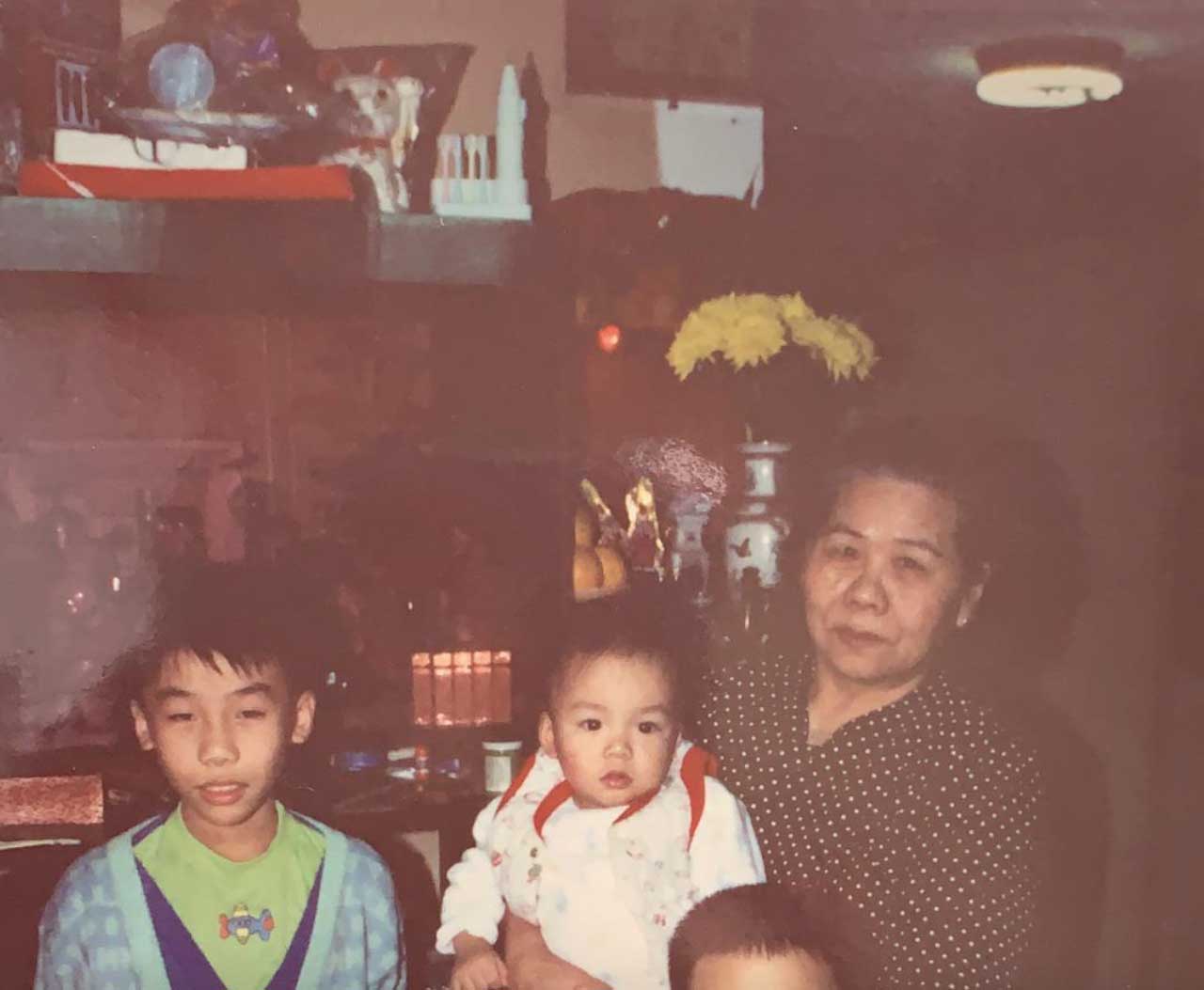

After the Rochester workshop, my intention to unearth the technical know-how and cultural knowledge of porcelain photos and photoceramics became solidified. I grew increasingly aware of these artifacts in everyday life. Porcelain photos permeate rituals of life and death in Hong Kong and the Sinophone. One can find traces of porcelain photos on gravestones in public cemeteries, at ancestral shrines in ordinary households, or as commemorative portraits of patrons and philanthropists in charitable institutions. I visited these sites to observe the artifacts and their varying styles and physical conditions. I also visited craftsmen’s studios to acquire knowledge of the technical aspects of making porcelain photos. Furthermore, I conducted oral history interviews with masters and craftsmen who professionally produce porcelain photos, collecting pieces of oral history from Hong Kong, Canton, and the 20th-century Sinophone. These experiences culminated in a community exhibition on the material culture of porcelain photos, titled Porcelain Photo in Hong Kong: A Mobile Museum, which I will elaborate on later. Here, I particularly want to express my gratitude to Dr. Kwok-wai Lau, formerly the Executive Director of the Hong Kong Resource Centre for Heritage (HKRCH, previously CACHe). I feel extremely fortunate to have collaborated with him and the Research Centre as a community partner. All these experiences ultimately led to the project’s conclusion featuring several academic conference presentations, notably at the “Chinese Objects and Their Lives” workshop organized by the Association française d’études chinoises in 2018, which resulted in a publication in the edited volume The Social Lives of Chinese Objects (Brill, 2023) by Alice Bianchi and Lyce Jankowski.

‘Portraits on China: Porcelain Portraits and Photoceramics from China in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’ (2023)

I once made a brief attempt to summarise a cultural history of porcelain photos within the Chinese context. This is an inherently challenging history to write, as very little primary historical documentation and evidence for vernacular arts and culture in 20th-century China are readily available or legitimate for research. Nevertheless, the artifact itself, as a photo object of significant anthropological value, is prevalent. I now consider that publication premature, simply because continuous scholarly effort is needed to enrich the history of porcelain photos, given that it remains a field with much unknown and uncategorised material. My essay examines the historical origins, development, and material culture of porcelain portraits and photoceramics in the 19th and 20th-century Chinese context.

Photoceramics were invented by French photographer Lafon de Camarsac in 1855. The technique and its vernacular application gradually spread to other European countries, North America, South America, and the Far East. Often taking the form of formal portraiture, the technique and knowledge of photoceramic making arrived at Chinese treaty ports such as Shanghai, Guangdong, and Hong Kong in the late 19th to early 20th centuries. It was then extensively employed for ancestral, memorial, and commemorative portraits in both private and public spheres. My essay discusses the French origin of photoceramics, its historical development in 20th-century China, and how photographic means influenced and informed “pasted portraiture”—a hybrid form combining painting and photography in portrait making. The essay highlights the aesthetic and vernacular aspects of photoceramics in Chinese society and the influence of photography’s introduction on Chinese portrait painting traditions.

The reason for mentioning this book chapter in the present essay is confessional. As I said, the book chapter was premature in the sense that several historical connections and information require further examination to fully demonstrate the transcultural occurrence and exchange of photoceramics in the Euro-American tradition and porcelain photos in the East Asian context. While I did try to separate the use of the two terms—photoceramics in the “West” and porcelain photo in the “East”—it is logical to connect, fabricate, and contextualize a global narrative of the subject matter’s discovery, patenting, travel, and adaptation. In principle, two critical connections seem to be missing and unproven. First, precisely how and who brought the knowledge and practices of photoceramics out of Europe and North and South America (the journey from Europe to the Americas being itself an intriguing research project). Second, precisely how to connect the practices of porcelain photo making from Jingdezhen, the capital of porcelain in China, to Canton, Hong Kong, and the broader East Asian context. These two outstanding research questions were not fully articulated or addressed in the book chapter, as there was no primary research material available or supported by field experience and/or extant knowledge at the time.

Field Trip in Taichung, Taiwan

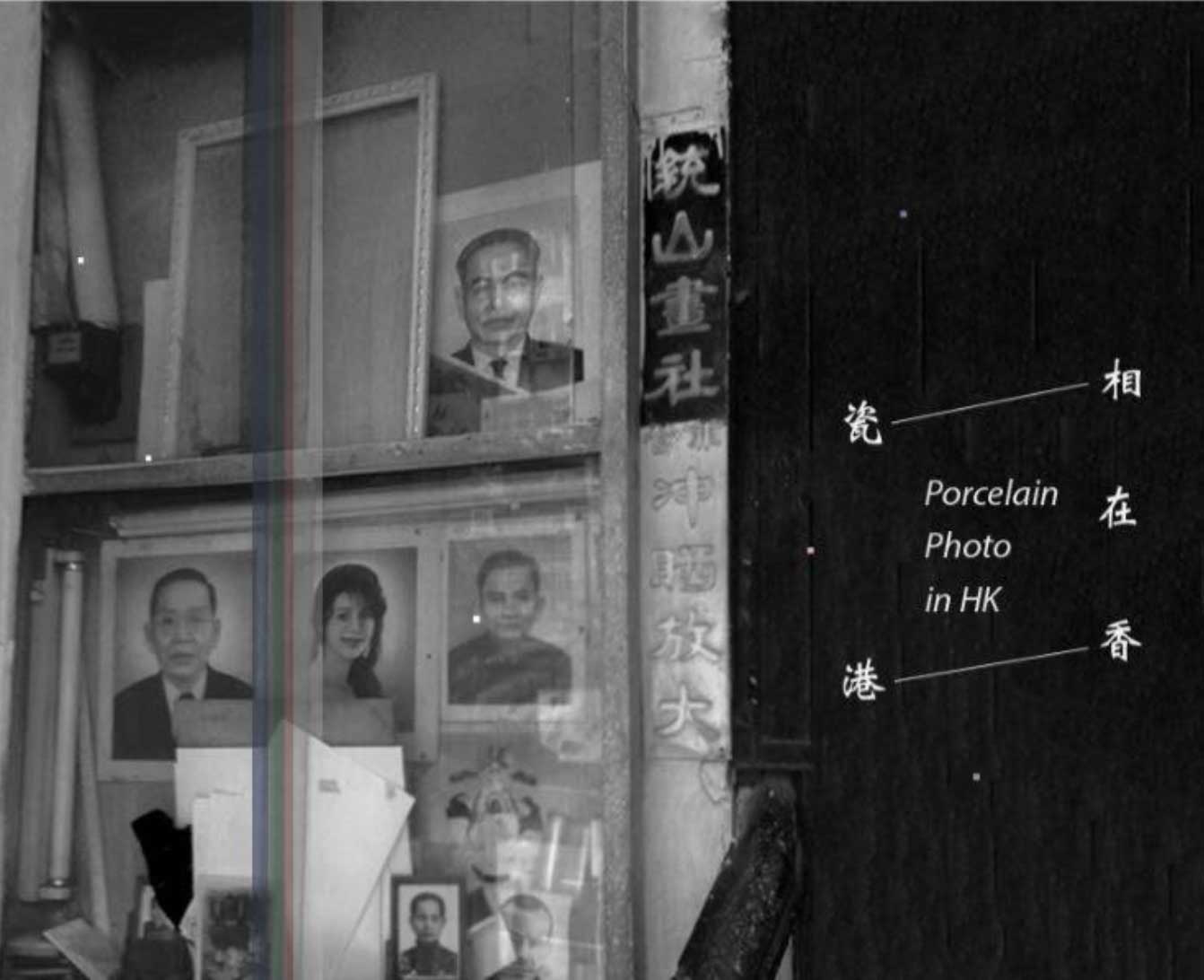

Soon after submitting the text to the proofreader, I received a text message from the son of Suen Ming (translation mine), a porcelain photo master active in Hong Kong and Macau in the mid-20th century, whom I had been researching. I identified this master’s name through numerous red inscriptions (also known as kuanzhi, a form of seal engraving and signature of the artist and/or maker) on painted portraits on porcelain, hybrid and pasted portraits (a combination of drawing and photographic imaging), and porcelain photos, some of the earliest of which date back to the 1950s.

Because of this text message, I was invited to visit Taichung, Taiwan, and meet Suen Ming’s son. I felt both fortunate and nervous. Conducting fieldwork is often a matter of chance; it is scientific yet not necessarily empirically appropriate to devise rigid procedures and plans for whom a researcher will meet, as this will inevitably be conditioned by the ambient experience and venue. There are always elements of openness and disconnection in field experience. I prepared myself with a list of structured yet open-ended questions and probes that I had pondered for years: Who was Suen Ming? What was his occupation? What was his upbringing like? What is his story in relation to a photographic subject/object of such significant anthropological value?

When Suen Ming’s son and I met, we greeted each other and sat at a dining table in his household. On the table lay a 4-by-3-inch black-and-white photographic portrait of a gentleman and a handwritten note. Mr. Suen, the son, humbly stated that he did not wish to interpret too much of his late father’s life. He simply handed the two artifacts to me, saying they would answer any questions I might have: a portrait of Suen Ming himself and Suen Ming’s story, handwritten by his eldest son. It was a socially distant, yet moving, moment. We then bid one another farewell.

Here, I would like to share these two unseen documents with the readers of Curatography so as to supplement some of the missing pieces in the book chapter (2023). It feels appropriate to first reach out to readers in Taiwan, then beyond.

Suen Ming (1898-1973), an Anhui native, traveled to Jingdezhen, Jiangxi, and acquired knowledge in making painted portraits and imageries on porcelain when he was 19 (approximately 1917). He migrated to Hong Kong when he was 24 (1922), initially working as a vintage buyer, then transitioning to making painted portraiture and porcelain photos as a formal business. At the bottom of the elegantly handwritten note, Suen Ming’s son also mimicked and depicted Suen Ming’s trademark, the kuanzhi, that I mentioned earlier.

There is a wealth of information in the handwritten note that requires further examination, interpretation, and triangulation with events, people, and other primary materials and evidence. However, it now provides evidence that Suen Ming brought the practice of porcelain photo making from Jingdezhen to Hong Kong in 1922. I wish to supplement this information in the cultural histories and material culture of porcelain photos in the Sinosphere.

Porcelain Photo in Hong Kong: A Mobile Museum (2017) Open for Circulation

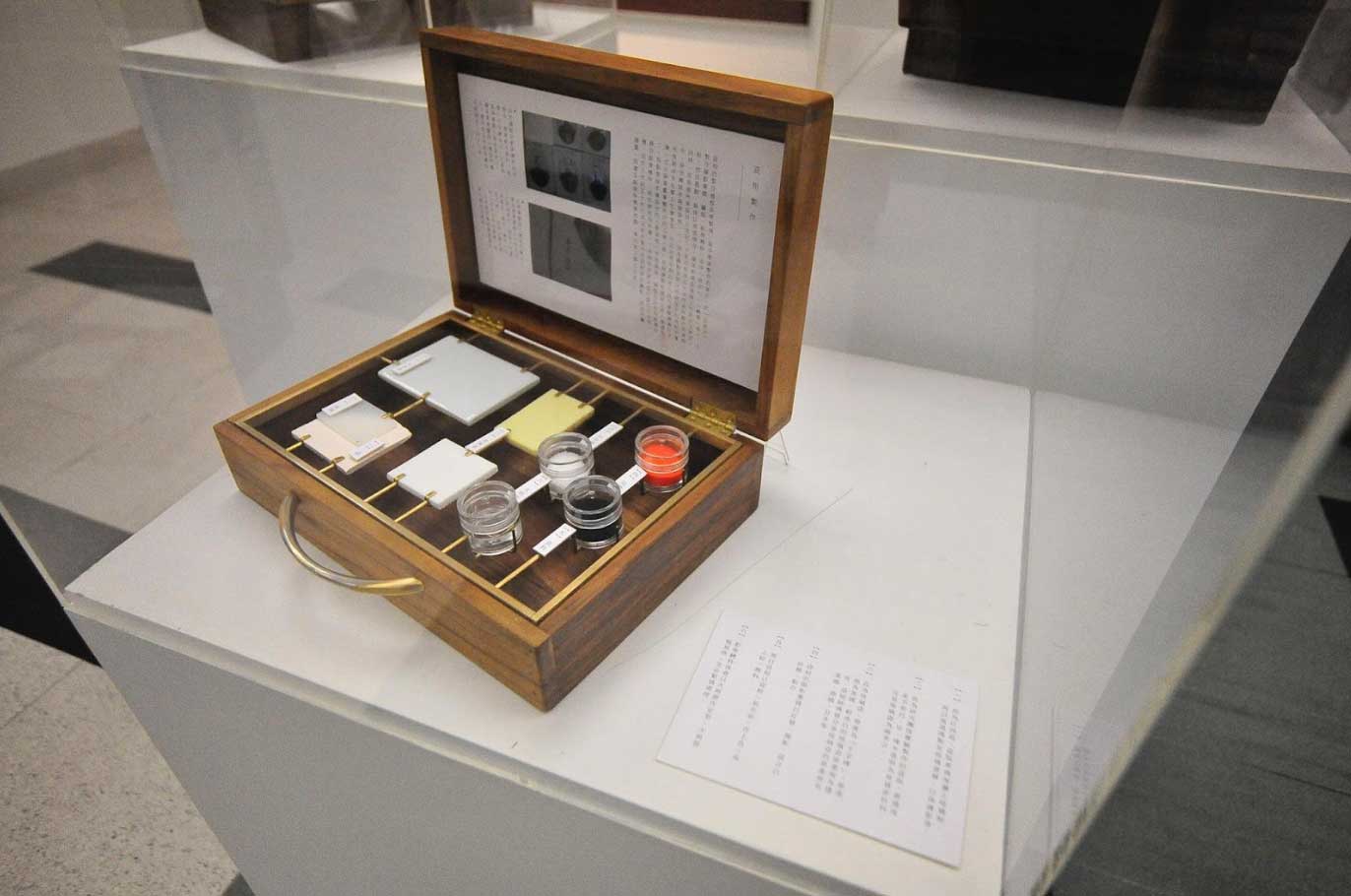

I would like to conclude this essay by introducing a curatorial project related to the research of porcelain photos in Hong Kong. Porcelain Photo in Hong Kong: A Mobile Museum presents a humble effort to synthesise and display the knowledge and material culture of porcelain photos in Hong Kong. An exhibition leaflet (written in Traditional Chinese), three wooden showcases, and a set of porcelain photo artifacts were consolidated into a mobile museum format for exhibition and travel. The project received financial support through a knowledge transfer project grant from Hong Kong Baptist University. These exhibits are now available for individuals, organisations, and institutions to borrow and thereby disseminate cultural knowledge about the porcelain photo.

The concept of a mobile museum was not original; museums and art collections are constantly in motion—traveling from one venue to another, engaging with diverse audiences. Artifacts are not as static as we might imagine, and we can actively curate them to create more, or better, experiences. The notion of mobility, in hindsight, has been deeply rooted in my artistic and curatorial practices for some time, aligning with my current position as a curatorial nomad. I hope the experiences shared in this essay will instill a sense of calm, comfort, and confidence in, and celebrate, the interest and study of everyday photography, photo artefacts, cultural practices, and beyond. These experiences may, concomitantly, serve as footnotes to the scholarly legacy and philosophical debates surrounding the central question of “What is to be done in curating?” addressed in the current issue of Curatography. Canons in the global history of arts and curatorial practice have undergone sweeping transformations at an exponential tempo. The idea to revolutionise these bodies of knowledge through a changing praxis, based on an evolving ideology, is not novel. The contemporary conditions of their presenting are shaped by the legacy and thoughts of ‘What is to be done?’ The meaning-making aspect of contemporary research, albeit formal publication and dissemination, to conclude, relies on being intellectually sustainable over time and being fluid across avenues and sites.