Curating is usually understood as a professional activity that requires a set of skills that bridge the rational, intuitive, and emotive and cannot thereby be categorized under specific disciplines, even though they are often captured by fine art, art history, anthropology, sociology, media, and cultural studies. The advent of content curation has further forced curating outside of these disciplines. It now concerns an ever-increasing range of practices: fashion, perfumery, archives, music, catering, advertising, commodities, personas, social phenomena, etc. Overall, curating is an attempt at ordering an ever-increasing range of symbolic cultural excesses.1 As Michael Bhaskar says, curating exists because of an excess that needs to be articulated and made digestible.2 Historically, a basic example is the museum’s wall ordering: artworks are ordered around the height of the line of vision of a human eye, with key works at eye level and lesser important ones either below or above. More recently, the same ordering process can be found, albeit vertically, in online curating with important works at the top and lesser ones, lower down in the scrolling process.

Whether horizontal or vertical (or any other non-visual ordering), curating is one activity amongst many within the great ordering of the world started in the Enlightenment—the first period that exposed excess on a grand scale—further developed during the Industrial Revolution and Colonisation with the advent of the superfluous and/or exotic object, and exacerbated to the nth degree by the capitalist ideology for which the production of goods needs stories and contexts to be appreciated over and beyond their monetary values. The trillions of personal, institutional, and/or commercial curatorial expressions in situ or online is enough testament to this obsession with ordering started 270 years ago. However, this ordering is not exclusively a process by which a curator gives value to things in a world of excess (beyond the monetary one, more often than not, aesthetic, social, cultural, or historical). It is more than this. Curating articulates the arbitrariness of lives into seemingly self-evident narratives; it forces the incoherent under coherent headings and subheadings (as well as evocative or enigmatic quotes intended to justify the coherence); it creates legends about the often-haphazard struggles of cultural endeavours, etc.

In order for this ordering to occur tirelessly across the globe in myriad ways, it requires a special agent, the curator who, alone or in committees, order(s) what needs to be researched, discovered, elucidated, articulated, exhibited, ideologized, evaluated, consumed, toured, stored, and/or forgotten. This agent has a growing hegemonic power because he, she, or they control all aspects of the undertaking, and therefore what is to be understood or misunderstood. In museal contexts, curators are embodiments of this hegemonic power, in as much as they sit between directors and exhibition organisers and act with the help of funders, collectors, and donors like governors, people who govern over a specific order for a determined period of time (e.g., long for a collection, short for an exhibition). The power of the curator can only either increase in the future—providing, of course, no global recession thwarts the seemingly never-ending dialectic of production and consumption and its de rigueur ordering (“here’s to next month’s show!”)—or progressively diminish through the advent of AI, creepingly reducing the profession’s skills to a set of trawling tasks. In the meantime, if there are symbolic cultural excesses to be ordered, then the curator’s power is here to stay.

Can curating adapt itself to a different order and thus operate differently?

To address this question, I will argue—this is the first part of my answer to Yenchi Yang’s question “what is to be done?”3—that there is another order that curating can follow and that is nature’s. Nature is an order not in the sense of a physical world or environment, but in the sense of anarchy, that is, of something already ordered. As I will try to argue relying on a number of anarchist and not-so anarchist ideas, anarchy is indeed order itself (hence the famous urban graffiti symbol of an A inside an O). Nature is anarchy and anarchy is an order and curating should heed it. The second part of my answer to Yang’s question is to diminish curatorial hierarchies and let all involved in contributing to the making of exhibitions irrespective of their degree of knowledge or qualifications. Curating can be done using a flat structure—if only curators allow it. With this double focus, I want to put forward the idea of a curatorial anarchy. In doing so, my aim is not to say that curators are no longer needed because it’s all ordered by nature or that their role is defunct in a flat structure, but that curating can take place differently, namely, on a par with nature and in a horizontal manner.

I will begin by briefly defining a couple of terms and then tackle the issue step by step. Please note: a) This essay is only conceived as a preliminary note towards a more expansive analysis. So, the ideas that follow are still in the process of being formulated. b) The title is “towards anarchy” and not “towards anarchism,” which is set of established political beliefs and strategies with many branches and directions (e.g., capitalist, communist, black4) and practices (federalist, mutualist, syndicalist, etc). Hopefully, the below clarifies this distinction as well as possible. c) Finally, I have limited myself to a few well-known figures in the formulation of anarchy.5 As such, the following does not aim to be a comprehensive analysis or overview of all the issues that anarchy raises with regards to symbolic cultural excesses,6 let alone curating or their ordering taskmasters who follow an infinitely diverse set of urgencies, trends, and/or tastes and abide to the dictates of production and consumption in many different market-driven societal and cultural worlds.

I. Lexicon

The order of nature: I follow Baruch Spinoza’s interpretation of this expression.7 This refers to nothing correct or in its place. However paradoxical, nature’s order can contain misguided sequences and patterns, mistakes and disarrays. In whatever way it occurs, the order can never not take place. Nature orders itself necessarily even when all appears disorderly. As such, it is not a system or network, which implies some linearity, grid, structure, organizing protocol even one self-learned. Nature’s order is also allergic to all forms of ontical (e.g., biological, cosmological, historical, etc.), ontological, or theological evolutions, including deliberate or contingent expansions or contractions, uni- or multi-verses, whatever their scale, origin or destination. Neither system nor evolution, nature’s order is therefore energy, i.e., the necessary and diffusive expression of nature occurring in no other way but the one it finds itself in.8 As such, there is nothing exterior to nature’s order (i.e., a landscape or environment). It is simply an energetic prodigality that occurs not out of a fatalistic logic, but because it cannot do otherwise.

Anarchy: I follow a diverse range of authors here: Anarchy is generally understood as a synonym for chaos, disorder, and lawlessness. However, anarchy is in fact the exact opposite. It means order. Anarchy is what happens wherever an artificial order is not imposed by force, when the order happens in a natural and necessary way. As such, anarchy refers to the energetic process of continual reinvention of nature, of ourselves and our relationships, a reinvention that occurs without any authority. Anarchy is thus the process by which nature orders itself out of necessity without anyone or anything butting in from above, within, or without. With regards to society, anarchy means a society based on cooperation without rulers or coercive power. A few quick preliminary examples are here necessary: a rain forest, a circle of friends, your own body, COVID mutual aid groups, informal shared childcare, an anarchist community, all occur naturally without hierarchal powers determining how it all comes together. As such, anarchy is grounded on a type of naturalism or emergent materialism which, in my case, is of Spinozist inspiration.

II. Anarchy Is Not Bomb Throwing, Antisocial, or Idealistic

I will start with a few negations. Anarchy is not throwing bombs. Governments have the monopoly of violence; they hold the largest arsenal of weapons and often kill with impunity. Recent examples (Russia, Israel, etc.) have demonstrated this again all too clearly. As the anthropologist Brian Morris says, “For over a century, liberal politicians and the media, whether out of malice, ignorance, or as political propaganda, have associated anarch[y] with violence and bomb throwing. But as many anarchist texts have emphasized… [t]he main holders and users of bombs as well as other forms of violence have not been anarchists, but governments.”9 So, by suggesting a curatorial anarchy, I am not suggesting that visitors should throw bombs at exhibitions, that curators should start using grenades, or that curators should only show works emphasizing destruction. Violence is the privilege of governments and terrorists for political and/or religious gains.

Anarchy, and curatorial anarchy to boot, is also not an overthrow of sociality or social interactions (e.g., pranking or satirizing social mores to ruin them). It does not aspire to terrorize the social sphere. It is, on the contrary, the concept of sociality itself.10 However, as I will show later, to function properly on a par with nature, sociality cannot have hierarchal powers for otherwise there is no cooperation among individuals, but obedience to whatever is elevated (e.g., pope, king, president, prime minister, etc.). As such, anarchy is sociality without structures of domination and in some cases oppression.11 With regards to curating, anarchy is therefore, sociality without authority or hierarchy (e.g., museum trustee, CEO, COO, CFO, artistic director, curator) determining the order in which the world and its cultural excesses need to be presented.

Similarly, while it seeks a non-hierarchal model of sociality, anarchy is also not the abolition of influence over others. It is only the abolition of privileges whereby some have more power than others, and charters and laws are established to maintain those privileges through hierarchal means of decision making. As the Italian anarchist Enrico Malatesta says: “we do not pretend to abolish anything of the natural influences that individuals or groups of individuals exert upon one another. What we wish for is the abolition of artificial influences, which are privileged, legal, official.”12 The wrestling of influences can thus continue with anarchy, albeit divested of unnatural power structures. This means that curatorial anarchy does not therefore aim at getting rid, as I will see later, of experts and specialists, but to abolish privileges, the authority held over others, less privileged, and the monopoly over the ordering of cultural excess.

Anarchy is also often understood as an idealism, something nice that will never happen because of the “natural” human propensity for domination (i.e., animalistic, phallocentric). In reality, anarchy is not something that will occur in the future. If this were the case, it would then posit itself as a telos to be accomplished in the style of communism. There can be no future time at which anarchy will occur because anarchy is already here, with us, now, in the idiosyncratic social ways that escape authority and privilege. As such, anarchy has simply not yet entered humanity’s consciousness. When it does, it “will become equal to saying natural order.”13 Similarly, curatorial anarchy is not a lovely idea in the future. It is what we already do when we refuse, resist, or ignore curatorial reductions like the ones arbitrarily imposed at biennales, triennials, quinquennials, and art fairs where some artists are elevated while others are relegated to the dustbin of history. There is no ideal; anarchy is already occurring; we just have to heed it.

III. Anarchy is Order

I now need to put forward some positive statements, namely what anarchy is and why it is an order. Some etymology: From an- “without” + arkhos “leader.” The latter is a noun made from the present participle arkhein, which means “what is first.” The word “anarchy” therefore means without a lead or the authority of what comes first.14 Ruleless, anarchy thereby considers how heterogeneity and variability can cohere by itself without artificial power. This is its most formidable challenge. It asks: how a diverse and restless society can occur without a ruler determining and coercing it from his, her, or their own privileged perspectives? In what concerns me here, it asks how a world can be ordered without the authorial and therefore authoritative gesture of a top curator imposing his, her, or their vision for the rest of us?

The original self-styled anarchist, Anselme Bellegarrigue, was the first to argue that “anarchy is order, whereas government is civil war.”15 Before briefly addressing this, it is worth highlighting here that Bellegarrigue’s famous sentence is first and foremost intended to disrupt the “common-sense” idea that governments are here to institute and maintain order. Common-sense is always dangerous, so it tirelessly needs to be challenged.16 The intention is indeed to shake the hard-wired belief that without a governing entity of some kind, life would be impossible. So, in addition to asking how heterogeneity and variability can cohere by itself without hierarchy, anarchy also disrupts the common-sense idea that order is always on the side of those in power. It isn’t, and this is what needs uncovering.

To begin doing so, it is worth noting that the cliché statement “anarchy is disorder” only arises because of the assumption that there is something otherworldly that is ordered. More precisely, people think anarchy is chaos because of a belief in an archē (a fixed preliminary will, principle, or substance) that “calls” the world to order. This archē is obviously inherited from religion. It stands for an obviously non-chaotic divine absolute (God or any other transcendent entity) that “commands” the view that anarchy is chaos and thus needs to be eliminated. This external phantom archē thus causes all the forces immanent to reality to perceive themselves as disordered. The outcome of this belief is the instalment of a governor who alone is capable of remedying the chaos. He is able to do so because he is anointed (the divine right of kings) by this imaginary archē, compelling “him” to orderly marshal the hordes of humanity back towards it.

Following this inheritance, it is thereby also common-sense that such a governor is the obvious guarantor of social order. Even if elected, governments still follow popes, emperors, and kings as the appointed (instead of anointed) governors of a hierarchal system compelled by an immemorial archē17. As the anarchist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon writes: “government and order are related to each other as cause and effect: the cause would be the government, the effect would be order.”18 The power of governors is thus secured by this unquestioned causality handed over by people’s will as if a divine order. Although no anointment obviously occurs in museums or galleries, the logic of the hierarchy is replicated in each organisation: someone is in charge of guaranteeing the order, not just of the exhibition, but of the good functioning of all institutional aspects.19

IV. Our Current Series and Arrangements

Now that anarchy as order has been sketched out, it is necessary to contrast it with today’s interpretation of order. Proudhon says that today’s perceived order is made up of “series and symmetrical arrangements”20 that cohere what seemingly needs to be ordered. A series is what is weighed, measured, and then serialised. They need not be logical. The aim is to constitute properties that somehow cohere together. A symmetrical arrangement is a rapport between two or more things. It gives a pleasing proportion of parts (e.g., the overall symmetry of works makes this exhibition pleasant to the see). A governor’s order is thus imposed as series or arrangements that cohere the presumed chaos of a society that resembles nothing like the archē against which it is pitched. This is quite obvious with curating: an exhibition is indeed a series or arrangement that gives the impression of some kind of order (e.g., the “row” in Weiner’s 1979 work “Many Coloured Objects Placed Side by Side to form a row…”).21

The important thing about these series and arrangements is that they are not real, they are images. Proudhon writes: “To discover a series is to perceive unity in multiplicity, synthesis in division: it is not to create order… it is to place oneself in its unifying or synthesizing presence, and through the awakening of the intelligence, to receive its image.”22 Even if we allow a series to be made up arbitrarily, we still see an image, i.e., a succession of effects, an acceptable arrangement. An exhibition that is arbitrarily open to any submission, for example, still obeys “arbitrariness” as its organising image. So instead of an actual order, we only have images, not fantasies, but images of series or arrangements telling us how the world ought to be ordered.

Over the course of time, these images (series, arrangements) get translated into a myriad of stories we tell ourselves. We touch here the way these images end up producing history and therefore, ideological narratives. Proudhon writes: “sensitive to the harmonies of nature, man thus sees everywhere number, cadence, alternation, and period… he conceives dramas and epics.”23 These narratives are our way of dealing with the order of nature, i.e., an anarchy in the idiosyncratic order of its own derivation, one that knows no series or arrangements and follows no imaginal dramas or epics. Many exhibitions obey or create images of series and arrangements and in doing so follow or construct their own ideological narratives (e.g., an art movement). Even the most radical off-site anti-establishment project that does not even call itself an exhibition (e.g., a manifestation) still abides to images precisely because it adheres to the cliché of a deviation from image-telling strategies.

Considering all this, it is clear why anyone in power and in charge of organising a world, is thereby allergic to anarchy, that is, to a world without series and arrangements, images, narratives, dramas, and epics. They need them. As Proudhon says: governors, “whatever their banner, are irresistibly repugnant to anarchy, which they mistake for disorder; as if their rule could not be achieved otherwise than through the distribution of authority.”24 Anarchy must thus be rejected because if it is allowed to flourish, series and arrangements would make no sense. Who in charge of an exhibition would admit to not master the series they have exhibited? Anything that does not fit the show or wrecks the series and therefore the cohesiveness of the authored narrative can only be omitted so as to secure the curator’s authority. Is incoherence not a curator’s greatest fear?

V. Towards Order

If any of the above sparks a questioning of curating as this ordering that replicates the greater ordering of society,25 with its problematic hierarchies and authorities and its origin in a phantom archē, the question can then be posed again, this time more precisely: Can there be a type of curating that evades authoritative series and arrangements and their narrations and espouses a more natural order, that is, anarchy itself? To begin answering this question, I fear it is necessary to clarify the path towards such an order.

Firstly, with anarchy or order, there is no archē or telos; there is no origin (re)conceived as destination. There is only anarchy, an order that needs nothing external to justify its occurrence. It’s similar to the way the second law of thermodynamics works irrespective of the first and third laws: in physics, the first and third indeed need to exist in order for the second to occur, for there to be entropy, for order to dissolve into disorder. But there is only order dissolving into disorder, there is only the second law, that is, anarchy. The first and third thus remain unprovable for to prove them would be to abolish the second. As such, the first and third, like the archē of societal hierarchies, cannot be used to explain what takes place now.26 Anarchy or order thus occurs regardless of any imaged referent(s).

Considering such an approach, it becomes clear that the first step in any recognition of anarchy as order is to think of it as a natural movement against anything that consolidates itself as a power claiming to order the world, a movement that refuses the series and arrangements it puts forward and evades the lure of their images. With regards to curating, this does not mean opposing museum directors and curators, but questioning their authority, fighting against their obsession with ordering single-handedly or in private committees a world with more series and arrangements, more images and narratives (whatever such a world may be: an artist’s output, a geographical zone, a temporal periodization, a political or social situation, etc.).

However, this preliminary movement against authority should not be seen as a transgression or violation of norms, agreements, laws. The reason is simple: in every transgression, there is already inscribed the possibility of further norms, agreements, laws. Anarchy, by contrast, assumes beyond transgression that there is something more fundamental at stake, namely the way norms, agreements, and laws are held in place by authorial rules whose existence is only justified by an inexistent origin-referent (archē). As Reiner Schürmann says: “The difference between transgressive and anarchistic struggles lies in their respective targets: for the transgressive subject, any law, for the anarchist subject, the law of social totalization.”27 Again, anarchy is not illegality. It is a movement that questions what sustains authority, the formation (or totalisation) of the social and its cultural excesses.

Finally, this movement does not also seek to overthrow expertise or specialism. As stated earlier, influence is not here called to a stop. The target of anarchy is hierarchy, privilege, and authority, not passions, enthusiasms, obsessions, fascinations, devotions, or fandoms. Expertise and specialism could instead be used to question the seemingly self-evident series and arrangements that lead to more hierarchy and privileged authority, asking questions such as “Is such a perspective not replicating a previous one that consolidated my power or those of my kin?” “Can such a view really challenge the status quo of which I am a part?” etc. In doing so, experts and specialists could then seek to establish a condition of anarchy or order. This means two things, leading me to the core of my argument. Firstly, it means to foster a type of action on a par with nature. Secondly, to curate through voluntary associations, flat structures, and a DIY approach.

VI. Acting Nature’s Order

As intimated in the lexicon, nature orders itself, so it is a question of letting ourselves be ordered following nature. This does not mean a bucolic fusion with an environment or an anti-anthropocentric matter-realist approach.28 As intimated earlier, this means acting with sociality. This is what anarchy or nature’s order is about. As Morris says, “Anarchist[s]… view both tribal and kin-based societies and everyday social life in more complex societies as exhibitions of the basic principles of anarchy.”29 This acting with sociality is based on a simple conviction: that people know how to live their own lives and organize themselves better than by decrees (mostly non-negotiable) and rules (often overruling previous ones) coming down from long-established hierarchal authorities. As such, when not coerced, there is no difference between nature’s order and the way people voluntarily order themselves. The question is what does this acting with sociality or with nature’s order look like?

To answer this question, it is necessary to first stress that nature, consciousness, and symbolic culture are not distinguishable from each other. These distinctions falsely shape our understanding of the world and our place and role in it. There is no nature as a background and some cultural artefacts in the foreground.30 As Morris says: “as evolutionary naturalists, anarchist[s]… [hold] that the world (reality) consists exclusively of concrete material things, along with their dispositions, qualities, actions (events) and relations with other things. Life, consciousness, and human symbolic culture are, therefore, all emergent properties of material things.”31 When not coerced into imaginal series, symbolic culture and its excesses are the order of nature, even when excessive or out of kilter. If anything, anarchy implies the idea of permaculture for which neither nature nor culture is distinguishable.

It is also important to stress that chance and contingency are part of this order, because such anomalies or disruptions are part of nature.32 As such, nature’s order can never be chaotic. As Morris says, “although chance and contingency are intrinsic to earthly existence, the material world itself is not chaotic…”33 Chance and contingency are therefore the product of human imagining, images of alternative events when in fact only one occurred, is occurring, or will occur. So, contingency fields in exhibition budgets (future) as well as narratives trying to make sense of chance or serendipitous events (past) are only images of what may or may not (have) happen(ed). As these images, they falsely transpose into artificial causal series or arrangements what cannot do anything else but happen. No images rule nature’s order or anarchy, not even its most random or probable events.

To make sense of how symbolic cultures can set themselves on a par with nature and not in an imitation of it, it is necessary to think what drives them. I use here a Spinozist term, conatus, which means to persevere in being.34 All of nature perseveres in being at any given time, even if it is ill or dying, even if it is still like an artwork, lifeless like an image, or hallucinatory like AI. A society operates likewise: a community has its own conatus, its own effort to persevere. As Malatesta says, “Man has two necessary fundamental characteristics, the instinct of his own preservation, without which no being could exist, and the instinct of the preservation of his species, without which no species could have been formed or have continued to exist.”35 Irrespective of how they go about it, societies, communities, institutions, and the objects they contain are thus congregation of conatuses, natural determinations to persevere.

However, at the moment, humanity’s conatus occurs mostly in a strife with nature which is, of course, a strife with itself. This is the sad recognition that our crony-capitalist world knows no other way of operating than through imaginary series and arrangements with their attendant graphs and expected profits. But there is another way. As Malatesta says, “in nature, living beings find two ways of securing their existence, and rendering it pleasanter. The one is in individual strife with the elements and with other individuals of the same or different species; the other is mutual support or cooperation without which no species could have been formed or have continued to exist”36 To increase our conatus and endeavour to acting with sociality therefore relies on the latter: mutual cooperation. This mutualistic symbiotic relationship that benefits not one, but all life forms must thus be re-emphasized to avoid extinction. Now that the broad outline of how anarchy, nature, culture, or order works, let’s address curating specifically.

VII. Curatorial Anarchy

Considering the importance of how nature orders itself, what type of work can then be considered? Morris writes, “creating a… society based on common ownership, self-management, and democratic planning from below, and on production for need not profit has always been fundamental to anarch[y].”37 The first difficulty here is how to distinguish between need and profit. From a Spinozist perspective, the answer is always about ends. Nature does not work with an end in sight, which is a mere image that colonizes the future in advance.38 Curating could then first evaluate its own functioning needs and operate without profit as its endgame (and without this other excluded-referent value—money—that dictates it39). This means emphasizing social value over imaginal targets and inventing other transactional ways determined by the bounds of association. Freedom from funders and sustainability can only begin by slow turning towards what seeks no return: sociality and its aspirations, modifying them, of course, in light of supply and demand and buffers unanimously agreed upon amongst all involved parties.

The second difficulty is “self-management.” I think the only way this can work is if there is a multiplicity of strategies that follow the needs of human associations all working on a par with nature. This multiplicity is crucial as anarchy does not support a one solution fit-all approach. As Morris says, “anarch[y] advocates a plurality of political strategies which become relevant in relation to… the different socio-historical conditions in which individuals and their associations find themselves.”40 The idea is not therefore to assume that a generic self-management is always generative of an improvement in human social conatus, but to insist on a plurality of political approaches based on voluntary associations where all workers have an equal voice. Curating could thus ensure that its working methods adheres to its own idiosyncratic plurality so that it combines all efforts and all voices for procuring the greatest possible well-being for all.

A third difficulty is this flat, horizontal, or “democratic planning,” which is intended to prevent the accumulation of powers in the hands of a few. Against having governors using “the physical, intellectual, and economic force of all, and obliging each to do the said governors’ wish,”41 anarchy or order fosters a spirit of co-operation and mutual aid that, because of its multiple strategy, should never congeal long enough for any one group to make itself central to (or dependent on) all others. In curating, this could mean distributing the various tasks that lead to an exhibition to all those involved irrespective of their degree of knowledge. If skill is required, then sharing the skill becomes part of the endeavour. Other strategies include strict equal pay, invariable rotating responsibilities, decentralising, avoiding custodial supervision, idiorhythmic work, and if artists are alive, involving them in decision making processes, etc. A flat operation is always more beneficial than a hierarchy.

Finally, no matter what authorities tell you, the driving force of a society’s conatus is acting with sociality. This might not be at first self-evident. As Malatesta says: “the vast solidarity which unites all men is in a great degree unconscious since it arises spontaneously from the friction of particular interests, while men occupy themselves little or not at all with general interests. And this is the most evident proof that solidarity is the natural law of human life.”42 A collective conatus is always the driving force, not some abstract or general interest. Is it not always the case that an organisation or an exhibition that pays attention to the interests of its members is more effective than one imposing its views from a single perspective and operating on the basis of a generic audience? This does not guarantee zero ego-driven manoeuvres but emphasizing and fighting for this natural law above all else risks nothing and gains everything.

If one takes on board these suggestions, it should become clear that a curatorial anarchy is therefore a type of curating that fosters co-operation, horizontality, and solidarity on a par with nature. This is not unattainable. As Malatesta says, anarchy “is not perfection, nor is it an absolute idea, which, like the horizon, always recedes as we advance towards it. It is instead an open road to all progress and to all improvement.”43 So, anarchy, this order, is neither a fixed state with no way out nor an idealistic promise that never materialises itself—both of which are exemplary of capitalism. Like nature’s order, anarchy (and curatorial anarchy specifically) is not perfect, it is an open path where a multiplicity of strategies and equal voices fulfil all of its members’ conatuses. As such, there is no methodological blueprint to follow or an orthodoxy to reproduce. An anarchic curating is simply constituted by the research problem a group seeks to explore together for its own good; a “hub of curly lines”44 as Yang says, but without a jet-setting über-curator telling everyone what these lines mean for the group.

But what does this mean for our current world where everything obeys hierarchies and authorities and is dominated by competition and conflict? As already stated, anarchy is an invitation to live on a par with nature, i.e., sociality. This means first refusing to take part in hierarchies and authorities, repeating, for example, Bartleby’s famous words: “I’d prefer not to.”45 As the anarchist Jeff Shantz says, “In order to bring their ideas to life, anarchists create… experiments in living, popularly referred to as ‘DIY’ (Do-It-Yourself), which are the means by which contemporary anarchists withdraw their consent and begin ‘contracting’ other relationships.”46 For curating, the idea could then be to start with this withdrawal of consent. For example, asking questions such as: Does the show need to use cloud-capital corporations to succeed? I’d prefer not to. What decentralised mode of communication or consumption is there that does no trade freedom for convenience? Persisting in that mulish course is one way to slowly disempower (oligarchic) authorities.

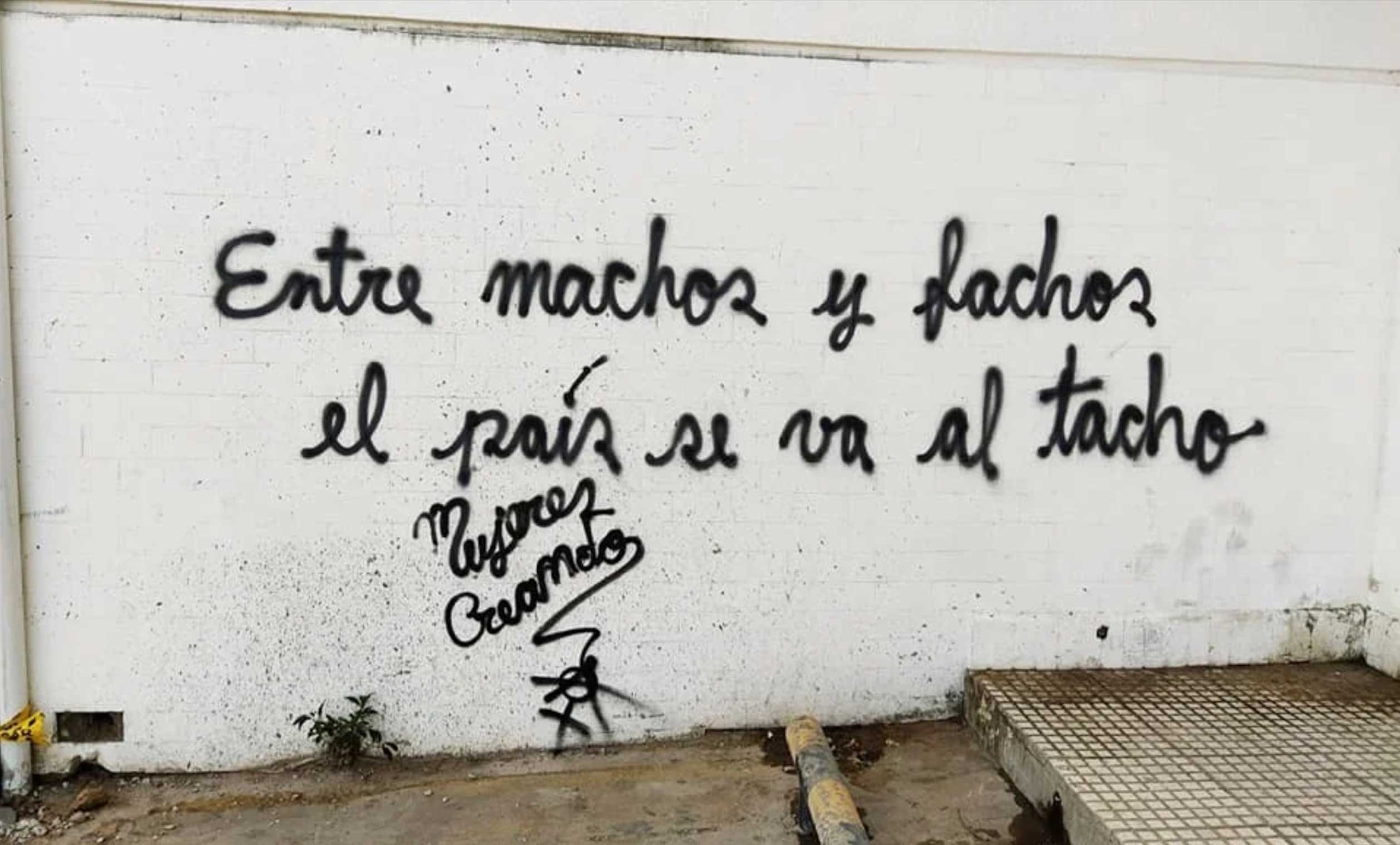

“Do it yourself” is also a possible strategy. As Shantz says, “The DIY ethos has a long and rich association with anarchism. One sees it as far back as Proudhon’s notions of People’s Banks and local currencies which have returned in the form of LETS (Local Exchange and Trade Systems). In North America, 19th Century anarchist communes, such as those of Benjamin Tucker, find echoes in the Autonomous Zones and squat communities of the present day. In the recent past, Situationists, Kabouters, and the British punk movements have encouraged DIY activities as means to overcome alienating consumption practices and the authority and control of work.”47 The cultural sphere is highly cognizant of iconoclastic artistic endeavours using DIY strategies. From Aleksei Gan or Tristan Tzara to recent anarcho-artistic endeavours, the list is long. I will only take one example: the anarcho-feminist Bolivian collective Mujeres Creando (https://mujerescreando.org/) who constitute themselves horizontally without any political or syndicalist affiliation and who, since 1992, create (and curate) street performances, building occupations, outdoor masses, graffities, and protests to defend rights and fight patriarchism and neo-liberal policies.48

There are many other examples worth revisiting so as to inspire new ways out of hierarchy, authority, and privilege. Shantz writes: “these include leaderless small groups developed by radical feminists, co-ops, clinics, learning networks, media collectives, direct action organizations; the spontaneous groupings that occur in response to disasters, strikes, revolutions and emergencies; community-controlled day-care centres; neighbourhood groups; tenant and workplace organizing; and so on. While these are obviously not strictly anarchist groups, they often operate [with] the memory of anarchy within them.”49 I must add here taking back and creating public spaces for without them there is no sociality.50 There are thus no ends to the inventive ways humans (including curators and artists) have increased their social conatus on a par with nature. It is just a question of revisiting them and implementing them anew knowing that perfection is antithetical to anarchy and experimentation is congruent with it.

VIII. Conclusion

What is to be done then? In broad terms, make archē and telos—from which power is founded and justified and with which ideological arrangements are created—ancient history so as to give way to mobile local determinations. The world is currently in the grips of a perpetual war due to antiquated hierarchal structures that are contrary to nature and therefore to human conatus. Tyrants, dictators, autocrats, despots, and commanders in chief without forgetting oligarchs and kleptocrats rule the planet marshalling it towards extinction because of their poor abilities to grasp the necessity to act on a par with nature, that is, with anarchy. There is nothing more urgent to be done today but to refuse to kowtow to the extant hierarchies and come together against any authority that cares little about the well-being of communities. Of course, this is not always possible, the pernicious distillation of hatred across the globe often prohibits it. But, when this is possible, this is our sole chance of not ending up as a mere blip in the vastness of an indifferent universe.

The answer is the same for curating: make archē and telos—from which authority is stealthily established to tirelessly marshal more imaginary arrangements—ancient history so as to give way to curatorial local determinations. No more cumbersome hierarchal institutions that impose an authoritative ideology insisting that: “this is the state of the world according to artists,” “this is the history according to this curator,” etc. These are mere imaginary arrangements that are antithetical to nature and to humans themselves. To curate as anarchy is to curate on a par with nature. A much more difficult task that requires to first say “I’d prefer not to,” insist on sociality over any other consideration, and embrace collective authorality to avoid authority. Would the art world not be better off if it paid attention to the way nature and culture perseveres in symbiosis, without master or end in sight? Let’s open the road to a new form of curatorial practice that is anarchic, horizontal, open, DIY, and where all endeavours are based on needs and local mutual interests.

If trustees, CEOs, COOs, CFOs, artistic directors, and curators let go of the advantages of their backgrounds, the privileges afforded by their education, and if they paid attention to all those who work “beneath” them, then a different way of curating could occur. If nature above all works in communal solidarity, would it then not be felicitous to also hear those who in the institutions have no voice, who invigilate, clean, repair, guard, view, and tidy up after curators have made their choices? By involving them from the get-go in all aspects of what is to be shown, a different route may thus be paved, one whereby, single-view series and arrangements become highly questionable. Only a horizontal approach to curating can provide concerned communities with an ordering that does not feel like a dubious top-down narration. Curatorial anarchy is a first step towards chiming with nature, not imitating it, but playing on a par with an order persevering in being with one and all.

To the question “do we then need curators at all?” the answer is “yes,” but only on the condition that the job is seen as a transferrable skill and not as a privileged power. The profession is obsessed with this power because curators alone are the ones always able to articulate and explain all the art on display. Against this, only AI is, at the moment, its most underrated and imminent threat. It’s the most easily replaceable job on Earth. The only saving options are either an emphasis on “affect and intuition” (i.e., what is not AI), but that, I fear, sends us back to the old times of the “connoisseur” and “the good eye” or an emphasis on an action on a par with nature (which AI will not be able to achieve) for which transferrable skills and a flat structure are key. If curators go with the latter to save their role from the tentacles of AI, then an anarchic curator will be someone who can help “order” the world without thinking that such an ordering is due to their privileged position.

As intimated earlier, anarchy is an open road. As Schürmann says, “As opposed to nineteenth century anarchism, the one that is possible today is poorer, more fragile. It has no linear narrative to justify itself, only the history of truth with its attendant history of the subject. But these are fractured by breaks. The transgressive subject still fetishizes the law in daring what is forbidden. The anarchistic subject echoes instead Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: ‘Such is my way; where is yours?’… For the way—that does not exist.”51 As these wise words intimate, there is no one answer to the question “what is to be done?” There is only a plurality of approaches to prevent hierarchies and authorities from ruining everyone’s lives. Curatorial anarchy as a strategy is, I fear, our only option but, as Schürmann says, “it is not an ought.”52 No imperative can be drawn from any of the above. This short note is only my attempt to think ways of overcoming the gloom that has set on all our horizons. Where is yours?53

1 I understand “excess” as meaning both overabundance and what exceeds the already known. Following sociologists, I understand “symbolic culture” as what is mediated and whose existence depends on collective belief.

2 See Michael Bhaskar, Curation: The Power of Selection in a World of Excess (London: Piatkus, 2017), 7-8.

3 For the way Lenin’s question implies the exhaustion of thought, see alongside works by Althusser, Badiou, Gauchet, and Nancy: Susan Kelly, “‘What is to be Done?’ Grammars of Organisation,” Deleuze and Guattari Studies 12, no. 2 (2018): 147-84.

4 I don’t address racialised anarchy here. For a brilliant analysis, see Lorenzo Kom’Boa Ervin, Anarchism and the Black Revolution (London: Pluto Press, 2021).

5 For introductory texts, see Iain McKay, An Anarchist FAQ (Chico: AK Press, 2008) and Sebastien Faure, The Anarchist Encyclopaedia (Chico: AK Press, 2019). There is a long tradition of anarchism in Taiwan, which continues today with Audrey Tang. Sadly, for lack of space and competence, I cannot address this here.

6 For art, see, for example, Josh MacPhee and Erik Reuland, eds. Realizing the Impossible: Art Against Authority (Chico: AK Press, 2007); Allan Antliff, Anarchy and Art (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp, 2007) and Michael Paraskos, Four essays on Art and Anarchism (Mitcham: Orage Press, 2015).

7 Baruch Spinoza, Complete Works, trans. Samuel Shirley (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002), EIVP4Pr., EIP23Pr., TPT§3:45, EIIP29Cor., TEI§84. This concerns a nature natured, i.e., neither our imaginary worldview, which are series and arrangements (see section 4) nor nature naturing, which would be humanly impossible. I cannot develop this precision for lack of space.

8 Spinoza, Complete Works, EIP33Sch.2.

9 Brian Morris, A Defence of Anarchist Communism (London: Freedom Press, 2022), 101-2.

10 Morris, A Defence, 91.

11 This includes the so-called “social contract.” As Bellegarrigue says, “The state of nature is already the state of society; it is therefore absurd, if not obscene, to want to impose, with a contract, what is already constituted as such.” Anselme Bellegarrigue, Manifeste de l’anarchie [1850] (Montréal: Lux Éditeur, 2022), 32, my translation.

12 Enrico Malatesta, Anarchy, trans. Vernon Richards (London: Freedom Press, 2009), 40.

13 Malatesta, Anarchy, 4.

14 Benjamin Tucker, Instead of a Book (New York: Tucker Publishing, 1897), 14.

15 Bellegarrigue, Manifeste de l’anarchie, 1, my translation.

16 On the dangers of common sense, see Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, trans. Joseph A. Buttigieg (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 624-707.

17 As Bellegarrigue says: “The transition from theocracy to democracy cannot occur based on mere ballot rights because such rights are only there to prevent governments from perishing, that is, to maintain… the principle of governmental anteriority.” Bellegarrigue, Manifeste de l’anarchie, 19, my translation.

18 Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Idée générale de la révolution au XIXème siècle (Paris: Garnier, 1851), 144, my translation.

19 The tie between museums and nation-building is well known. See, amongst other, Didier Maleuvre, Museum Memories (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

20 Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, De la création de l’ordre dans l’humanité (Paris: De Prévot, 1843), 1, my translation.

21 For an allegory on this issue, see Jorge Luis Borges, “The Library of Babel,” trans. James E. Irby, in Labyrinths (London: Penguin, 2000), 78-86.

22 Proudhon, De la création, 212, my translation.

23 Proudhon, De la création, 135-6, my translation.

24 Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Les Confessions d’un révolutionnaire (Paris: La Voix du peuple, 1849), 46, my translation.

25 On this replication, see Peter Aronsson and Gabriella Elgenius, eds., National Museums and Nation-building in Europe 1750-2010 (London: Routledge, 2015).

26 On this topic, see, for example, Eric Johnson, Anxiety and the Equation: Understanding Boltzmann’s Entropy (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018).

27 Reiner Schürmann, Tomorrow the Manifold – Essays on Foucault, Anarchy, and the Singularization to Come (Zurich: Diaphanes, 2019), 29.

28 New materialisms seem to be wary of anarchy perhaps because its intra-active agentism still hangs on to some privileged and thereby hierarchal logocentric rationale for its articulation. For lack of space, I cannot address this topic here or how it compares with Spinozism. See the work of Karen Barad, Jane Bennett, Elizabeth Grosz, Rosi Braidotti, Vicki Kirby, amongst others.

29 Morris, A Defence, 17.

30 On this topic, see Vicki Kirby, ed., What if Culture was Nature all Along? (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017).

31 Morris, A Defence, 19.

32 Spinoza, Complete Works, EIIP44Cor.1, Letter #54.

33 Morris, A Defence, 94.

34 Spinoza, Complete Works, EIIIP6, EIIIP7Pr, EIIIP59Sch.

35 Malatesta, Anarchy, 8.

36 Malatesta, Anarchy, 15.

37 Morris, A Defence, 111.

38 Spinoza, Complete Works, EIVP52Sch.

39 Just like arché and telos, money is another excluded referent that regulates all economic and social exchanges. See Karl Marx, Capital: Vol 1., trans. Edward Aveling (New York: Lawrence & Wishart, 2003), 79. For a revaluation of value beyond capitalism, see Brian Massumi, 99 Theses on the Revaluation of Value (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018) and with regards to curating, see Hongjohn Lin, “The Economy of Curation and the Capital of Attention,” Curatography 13 (2025), https://curatography.org/13-0-en/

40 Morris, A Defence, 128.

41 Malatesta, Anarchy, 7.

42 Malatesta, Anarchy, 21.

43 Malatesta, Anarchy, 37.

44 Yenchi Yang, “In Praise of Troubleness,” Curatography 13 (2025), https://curatography.org/13-3-en/

45 Herman Melville, Bartleby, The Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street (New York: Melville House, 1856), 201. See also Giorgio Agamben, “Bartleby, or On Contingency,” in Potentialities (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 243-71.

46 Jeff Shantz, “Anarchy Is Order: Creating the New World in the Shell of the Old,” Media/Culture Journal 7, no. 6, unpaginated, https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2480.

47 Shantz, “Anarchy Is Order.”

48 For a comprehensive overview, see Maria Galindo, Feminismo Urgente: A Despatriarcar (Buenos Aires: Lavaca, 2022)

49 Shantz, “Anarchy Is Order.”

50 I’m thinking here specifically of the movement Reclaim the Streets (or Beach) as well as artists’ green spaces (Agnes Denes, Mel Chin, etc.) and guerrilla gardening.

51 Schürmann, Tomorrow the Manifold, 29. For Nietzsche’s quote, see Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. Adrian del Caro (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 156.

52 Schürmann, Tomorrow the Manifold, 29.

53 I would like to thank Magdalena Holdar and Daniel Siedell of the University of Stockholm for their feedback and suggestions.