Curating Speculative Feminism

The Convergence of Three “Michelle Chens”

That morning, as usual, Ayu left home at 4 a.m. to get to the central kitchen of the factory in time for work. There she prepared ingredients, cooked, and portioned dishes without a moment’s pause. It was not until eight o’clock that she took her first bite of the day. After washing all the dishes and taking a brief rest, she entered the next cycle of preparing lunch. At two in the afternoon, she changed out of her uniform and was about to head to the leather-goods factory to begin her second job of the day, as a worker on the production line. Just then, the kitchen supervisor told her she had a phone call.

“Are you May’s mom? I am her homeroom teacher.”

“Yes, is everything OK?”

“Ms Lin, your child has been waiting at school for a long time for you to pick her up.”

Ayu was puzzled. Her child had always been independent; ever since the third grade, she had taken the bus to and from school on her own. The teacher cut into the silence on the phone: “Ms. Lin, public security hasn’t been very good lately. Ever since the Pai Hsiao-yen kidnapping case, the school requires parents to pick up their children in person, otherwise they can’t leave the school grounds.” Ayu did not know how to respond to this sudden change. Should she request leave from the factory first? Or go straight to the school? And from now on, would she have to pick up all three of her children separately every afternoon? What about her work…?1

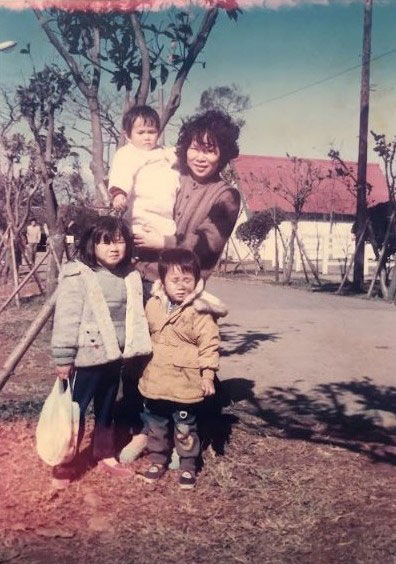

Since the day her husband abruptly stopped coming home, Ayu had been raising the three children by herself. Her life was like a small gear inside a vast machine, constantly turning, never stopping. The kitchen, the factory assembly line, and the at-home product assembly work she took on left no room for the slightest disruption. She barely had time to look at a newspaper, and even if she had, she wouldn’t have been able to read it. The events regarded as shared memories of that era — humans landing on the moon, Taiwan’s Little League world championship, Taiwan’s withdrawal from the United Nations — passed unnoticed by Ayu, who lived in a rural village where children were first and foremost part of the household labor force. From a young age, she was expected to herd cattle and care for her younger brother, receiving no formal education at all. Even the shared experience of many of her generation, being forbidden to speak Taiwanese Hokkien at elementary school, was never part of her life. At fourteen she started on the production line as a factory girl; nearly illiterate, she was insulated from newspapers and magazines, excluded from the systems of public knowledge. For her, life was straightforward: earning enough to get by. No one would have imagined that the fate of a stranger elsewhere on the island would suddenly change the entire structure of her own life.

The fear that belonged to that era was like a dark shadow hanging over my own mother “It’s better not to go out at night,” she would remind us from time to time, even though she had once worked abroad on her own while raising four children, even though she had been a supervisor in an electronics factory, and even though nearly twenty years had passed in Taiwan without any reports of kidnapping cases.

An event that happened to a single individual — one could even call it a private matter — spread and intersected in multiple forms, generating a fear that permeated an entire society. That fear became an invisible hand, shaping the behavior of a whole generation of women. A factory worker, a popular entertainer, a supervisor in an electronics factory. Three women who had never met found their lives converging at this moment, affirming that society exists as a network. Each entity is linked to others by a relational thread, and when one point is lifted high and then thrown down, it sends out a wave that ripples throughout the web.

The Silencing of “Mother”

One cannot ask, “Who is Venus?” because it would be impossible to answer such a question. There are hundreds of thousands of other girls who share her circumstances and these circumstances have generated few stories. And the stories that exist are not about them, but rather about the violence, excess, mendacity, and reason that seized hold of their lives, transformed them into commodities and corpses, and identified them with names tossed-off as insults and crass jokes. The archive is, in this case, a death sentence, a tomb, a display of the violated body, an inventory of property, a medical treatise on gonorrhea, a few lines about a whore’s life, an asterisk in the grand narrative of history.3

—— Saidiya Hartman, Venus in Two Acts

Looking back, the demands we put on our mothers when we were growing up was treated as natural; when faced with a distant or ineffectual father, the phrase “men just aren’t good at expressing themselves” became a kind of panacea.

Within our dominant cultural narratives, there is no place for a “good mother” who is unwilling to sacrifice herself for the family. In the film and television works that accompanied our upbringing, from Star Knows My Heart (1983) to Little Big Women (2020), the qualities of a “good mother” are consistently bound to domestic competence, reinforcing the myth of motherhood: a “good woman” must take on the work of a housewife, must dedicate herself to the family. The negative models absorbed by a generation of “Michelle Chens,” in series such as The Heart with a Million Knots, Outside the Window, and Romance in the Rain, depict “bad women” with a shared set of traits: financial independence, careful self-presentation, and a commitment to articulating their own emotional needs. The subtext of mainstream culture is clear: we do not permit “mother” to feel worn out by, or resistant to, the demands of care. She must regard it as a sweet suffering that she must learn to endure.

As we peel back the sugary coating of the “myth of motherhood,” a carefully orchestrated trap gradually comes into view. The role of the housewife, long constituted by unpaid labor, has sacrificed women’s bodies and time to supply the patriarchal order with free domestic work. In a capitalist world, what cannot be quantified effectively does not exist; domestic labor is kept outside monetary calculation, erasing its value and diminishing women’s significance and influence within the larger social structure. This mechanism also sets up a “tortoise and hare” dynamic in any competition between genders, ensuring that women devote most of their energy to the minutiae of daily household tasks, leaving only their remaining fragments of time and strength for self-development or self-expression. It prevents women from easily entering leadership roles or becoming part of heroic narratives.

When viewed through the lens of “heroic history”, a mother’s labor in sustaining a household appears trivial, not even worth mentioning, much like the countless nameless women in the history of art who were referred to simply as “muses”. The occasional praise for motherhood resembles awarding an “employee of the year” title, harmless and inconsequential. Or, the mother is framed through a slightly sympathetic filter, positioned as a “victim,” as though she must be a fragile injured party in order to be worthy of notice, her vulnerability and pleas for help required to fit the damsel-in-distress storyline. In this way, narratives about women cannot be separated from tragic descriptors.

Buried beneath the accumulated weight and oppression of history, the mother before us has gradually become distorted, unsure of herself and silenced by the multiple constraints imposed on her labor, emotions, thoughts, and affect. How might we help her take off her work clothes, hold her, touch her face, and allow her to see herself in an unburdened state? To let her speak of every pleasure and every anger, every love and every hate, everything great and small.

I set aside mainstream narratives and the dominant historical frameworks and research methods.

Them and “Her”

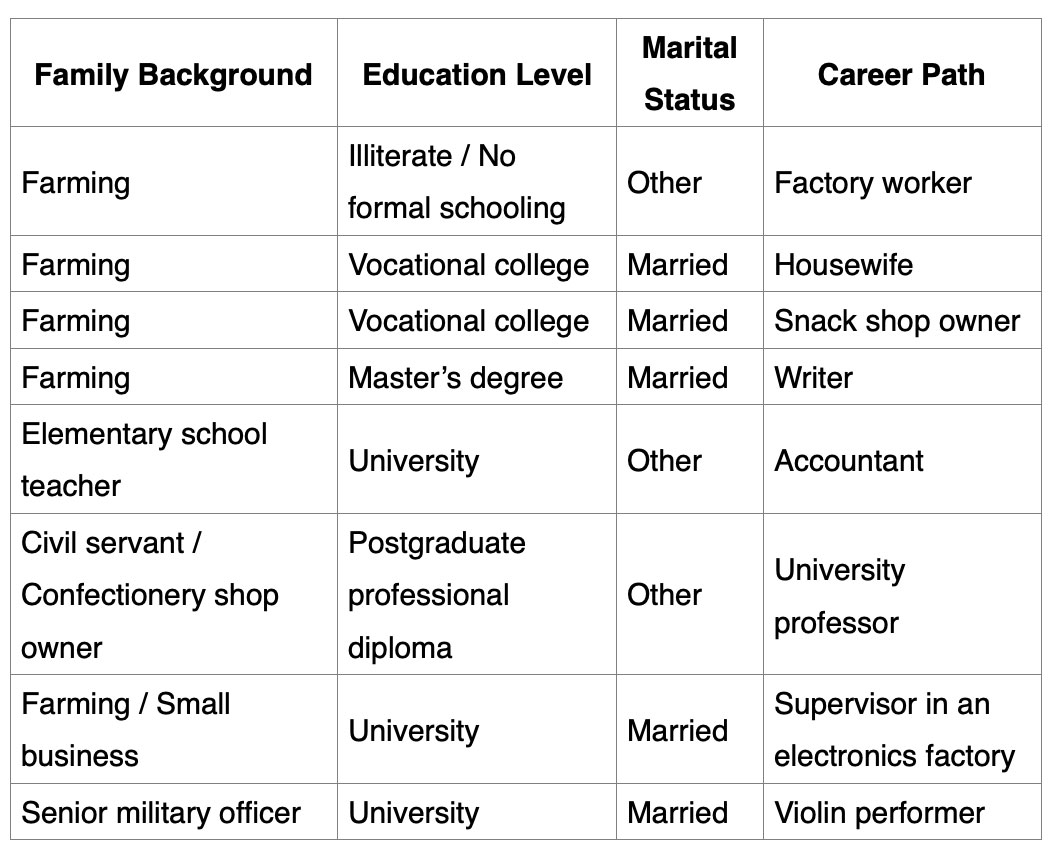

With careful aim, I slide a blade gently into Taiwanese society and cut out a thin cross-section based on age and gender to use as a sample: eight women born in the 1950s. Guided by linear time, I listen closely to their childhood family backgrounds, their educational and social experiences, their work and environments after entering society, and their present conditions. Their information can be mapped across four dimensions as follows:

These eight life histories were then edited and collaged into a single woman with the familiar and commonplace name —“Michelle Chen.” She is a factory worker holding down three jobs a day; a housewife whose husband died suddenly; a Taiwanese manager posted to mainland China; a bestselling author of nearly a hundred romance novels; a National Award for the Arts recipient; a violinist who once commanded the stage at Kiss Disco. She is no longer confined to a single social class, nor bound to any predictable future or ending; she moves fluidly through interstitial spaces.

In this “ritual of reanimation”, “Michelle Chen” is not summoned into a world where she feels out of place; instead, the audience is guided into her time and space, invited to understand what she went through. Michelle Chen’s Room, a research-based documentary exhibition, serves as a time capsule.4 Through montage, the events and objects mentioned by the eight women during their interviews are assembled into what appears to be the living space of a single individual. At this point in her life, Michelle has just graduated, has a stable job, and has not yet married. The television plays the cartoons, dramas, and the news she misses (or remembers?); the radio broadcasts her favorite programs and campus folk songs; the bookshelf holds the texts she once read. Together, they form the sensory and cognitive world that shaped her. The edited interview recordings were organized into six sub-themes, each placed upon a different piece of furniture: “Father/Husband” sits in the main armchair; “Mother and Food” rests on the dining table; “Political Memory” is tucked into the newspaper rack; “The Formation of Knowledge” lies flat on the bookshelf; “Work Experience” gathers on the sewing table; and “Lifetime Fears” is placed on the bed.

When we lay this collective biography out in a linear way, we begin to see that these eight seemingly disparate life stories in fact share a single overarching narrative; that is, the “chronicle of Taiwanese society” Michelle Chen has experienced. History, the hidden director behind the scenes, slowly takes shape. Everyone living within the vast backdrop of a given era appears to possess free will, yet the choices they make are made without an alternative, as they are imposed by their wider environment.

When Michelle was a child, students who spoke Taiwanese Hokkien rather than Mandarin at school would be given a time-out; during the Little League World Series, the entire village would gather at whichever household had a television: that was the first emergence of “Taiwan’s pride.5” During her school years, Taiwan withdrew from the United Nations, and campus folk songs swept across the island over radio broadcasts. When Michelle first entered the workforce, martial law was lifted; the matchmaking program I Love Matchmaker6 appeared on television; Taiwan became one of the “Four Asian Tigers,” and in Taipei, “awash with money,” speculators multiplied while public safety declined. As she reached middle age, Taiwan changed its ruling party through electoral means for the first time; a large number of manufacturing plants moved abroad; the Sunflower Students Movement emerged. Now, after she reached retirement age, Taiwan passed its marriage equality law; soon after, the pandemic hit and rapidly accelerated the digitization of daily life.

Michelle had never imagined that the Taiwanese society she had lived in and watched all her life could one day take on a form she no longer recognized. Caught in the irreversible torrent of history, she wants to speak yet swallows the words. I imagine her unresolved thoughts, her restrained emotions, and the posture of her resistance within that freedom she never truly had.

A Story Beyond the Impossible

The local train swayed back and forth. On one side, there was a green mountain wall covered in broad-leaved trees, while on the other side, there were clustered, cream-colored cement huts, outdone with corrugated iron roofs in a shade of matcha green.

“I was just thinking…” Michelle Chen fixed her gaze on those colors outside the train. She paused. She was trying her best to envision the words she wanted to say, “I never really wanted to be part in the Chang’s and suffered from all your sad shit.”

The pauses in her speech intrigued me. What else was she thinking during those paus- es? Had she thought about who she used to be? This Michelle Chen speaking in front of me was different from the one in the past. She spoke more, and her sarcasm had increased. I wondered if her love for me had also grown.

“The black sparrow flapped its wings again,” she said, staring at the red sunset shimmering between the buildings outside.7

—— Kao Po-Lun, Curatorial Statement Black Sparrow

Only by breaking away from the linear method of historical narration can the past come into view, that past that never came to be. The millennial novelist Kao Po-Lun created the short story Black Sparrow, centered on parent-child relationships, as the curatorial narrative for this exhibition. The story is told from the perspective of a gay male protagonist who looks back on his mother, “Michelle Chen,” who died young due to cancer. In the narrative, “Michelle” is at times a memory and at times an imagined presence, allowing the temporalities of two generations to overlap and drift through one another.

We can no longer clearly distinguish whether “Michelle” is the woman speaking before us or the consciousness in Kao Po-Lun’s fiction, but we are certain that she exists in this exhibition. Michelle Chen weaves together the factual world of the mother’s generation and the imagined world of the child’s generation, writing a counter-history at the intersection of history and fiction. It is an attempt to revisit the scenes in a mother’s life in which she was compelled to obedience, without reproducing the grammar of patriarchal violence.

Her presence is the steady expression beneath Shiy De Jinn’s paintbrush; the nearly invisible dusting of pollen filling the bench in Chuang Hsin I’s Être de l’absence; the momentary tremor in the endlessly turning body of Kawita Vatanajyankur’s The Spinning Wheel; the footprints that appear in the domestic spaces of Lii Jinn Shiow’s Self-Portrait in Progress; the figure of a hero in Wu Mali’s “Lay Down For the Nation” timeline8; and the yeast in Mirna Bamieh’s To Jar, transforming decay into nourishment and proliferating without end.

The complex emotions intertwined within intergenerational parent-child relationships in the novel — longing, affection, attachment, irritation, resentment, and grievance — emerge in the exhibition and become part of the viewing experience, something that can be sensed, reflected upon, and even dissolved. These emotions form a nonverbal communication, a “language” through which the temporalities of two generations permeate.

Our relationship with our mothers is present in Hung Wei Lin + Hsin Pei-Yi’s Champ-Contrechamp, where two figures seem to sit facing each other yet remain continuously out of alignment; it is there in Lydia Li’s Bridge, in the everyday objects that appear fragile and sensitive yet hold one another in place. Through a phone screen we face “mother,” our conversation shifting from awkward to warm. Climbing the stairs, we encounter her again, sitting in her living room at ease. This scene became a slice of domestic life cut out and transplanted into the museum. Behind the glass case, she feels both deeply familiar and impossibly distant.9

As if she had never been my mother at all, her selfless devotion to the family spills over from society’s expectations of women: “marry a chicken, follow the chicken; marry a dog, follow the dog.” This is the life lesson taught to that generation of women: that they could be made whole only through the family. They had no alternative path; wherever they turned, they had to confront it, loving, suffering, by turns prominent and insignificant, moving back and forth between the individual “self” and the broader societal “Self”.

“Don’t you have any dreams?”

“Not everyone has dreams like you. Some people simply want to make a home and live their days quietly.”

That woman appeared again, driving that oversized white SUV that always seemed too large for her.

“I want to stop and have a cigarette.” She rolled down the window; the lighter flickered, and she handed it to me.

“Do you still remember what you were like at thirty?” I asked.

A cigarette usually contains only nicotine and tar, but as we exhaled, our eyes grew hazy. I couldn’t tell whether the mist drifting in was from outside the window or from our own smoke. My body loosened without my noticing, stretching slightly as if trying to find a comfortable posture; even time seemed to slow down to wait.

Only then did I finally make out her blurred face through the smoke.

“Not really,” she said. “Maybe a bit like you now.”

Miss Bench

Written at home in Fuzhong

November 7, 2025

Postscript

Michelle Chen is an exhibition that unfolded between 2023 and 2025, taking Taiwanese women between the ages of 60 and 70 as its primary focus. Utilizing a combination of fieldwork and fictional writing, the project invited novelist Kao Po-Lun to co-create a fictional character, “Michelle Chen,” grounded in real life experiences. His novel Black Sparrow serves as the curatorial statement for the project. The project was presented in two phases. In 2023 at TheCube 7F, Michelle Chen’s Room, a documentary exhibition, staged a single suite setting to display interview documentation gathered during the early research phase. In 2025, Our Museum at the National Taiwan University of Arts presented Michelle Chen as a contemporary art exhibition featuring artists Wu Mali, Lii Jiin Shiow, Chuang Hsin I, Hung Wei Lin + Hsin Pei-Yi, Lydia Li, Shiy De Jinn, Co-coism, Mirna Bamieh, and Kawita Vatanajyankur. The works spanned painting, sculpture, video, installation, and live performance, guiding audiences to sense how “Michelle Chen,” as a woman and a mother, responds to shifting social circumstances with resilience. The exhibition sought to open up points of intersection across generational differences. Through three non-parallel narrative layers—three real-life women, the general situation of women of that time, and the fictional women in the exhibition, this essay attempts to set out a mental map of the curatorial process.

1 Interview with Ayu Lin, conducted in Tucheng, New Taipei City, on August 14, 2023.

2 “The Pai Hsiao-yen Case: A Full Account.” Pai Hsiao-yen Cultural and Educational Foundation, accessed November 1, 2025, http://www.swallow.org.tw/index.php/about/begin.

3 Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14, https://www.timesmuseum.org/cn/journal/south-of-the-south/venus-in-two-acts.

4 Miss Bench, “The Documents of Michelle Chen’s Room,” ARTOGO, accessed November 3, 2025, https://artogo.co/zh-TW/exhibition/michellechen/space/SJP4yGzE1SX.

5 The first instance of “Taiwan’s pride” emerged in 1969 with the Taichung Golden Dragon Little League Baseball team. They defeated Japan, the 1968 champions, to win that year’s title, Taiwan’s first-ever world championship in the tournament.

6 I Love Matchmaker was the first televised dating program in Taiwan’s broadcasting history, premiering on October 30, 1982, from 18:00 to 19:00.

7 Kao Po-Lun, Black Sparrow (short story, 2023). Later developed into the novel Youth at the End of Days: After the Wasteland (Ink Publishing, 2025).

8 Wu Mali, Formosa Club, 1998. Wood panels, pink foam, red light bulbs, sofa, Styrofoam, gilded wooden frame, and other materials; dimensions variable and adapted to the site. The work reconstructs a licensed brothel, placing at its entrance a timeline titled “Lay Down For the Nation,” written from the perspective of sex workers. This timeline reframes Taiwanese history by revealing the contributions of women sex workers to Taiwan’s political and economic development.

9 Co-coism, The Gaze of the Mother Upon You, 2025, interactive performance, commissioned for the Michelle Chen exhibition. Installed in the central stairwell, the work greets viewers with a ringing phone displaying an incoming call from “Mom” as they make their way to the second floor. Viewers may choose to answer or ignore it. If they pick up, a middle-aged woman appears on video, engaging in a casual conversation, asking about choosing a gift for her son, or how to enlarge text messages on her phone. After ending the call and continuing up to the third floor, viewers encounter the same woman behind a glass case, seated in a small room furnished like a living room, quietly going about her activities.

Share

Author

Ileana Tu holds an MA in Curating and Collections from the Chelsea College of Arts, UAL. Her research interests focus on how art can maintain its sovereignty while serving as a catalyst for public dialogue, and she explores models of art institutions that exist in a “state of exception” between the educational value of museums and the commercial value of galleries. She has previously served as the coordinator of the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, assistant curator of TheCube Project Space, and specialist at the New Taipei City Art Museum. Ileana started her writing and curating experiment in the name of “Miss Bench”, this idea came from her observation that contemporary art in Taiwan is turning too academic for the general public. Miss Bench’s curatorial practices include Abnormal (2018, London), // (2018, London), O//O (2019, Taichung), Home Land Is Land—— Retrospective Tour of the Failure Artist (2021-2022, Online, Taipei, Taichung, Kaohsiung), The Room of Michelle Chen (2023, Taipei), Michelle Chen (2025, New Taipei City).