The Economy of Curation and the Capital of Attention

What is the difference between a human and an animal?

For 38 years, the Katratripulr Indigenous community has resisted the appropriation of their ancestral wetland. First taken in 1985 by the Taitung government to build “Asia’s first Disneyland,” the wetland was later re-appropriated for solar energy development as Taiwan shifted toward green initiatives. Generations of Katratripulr children have grown up as activists, fighting for their traditional territory.

The Truku community faces a similar plight, with Asia Cement Corp being granted permission to blast mountains for cement. So as Ruisui(瑞穗, Amis: Kohkoh)’s hot springs, Sun Moon Lake’s Peacock Garden… — across Taiwan, numerous Indigenous lands are often caught in a conflict triangle between government, residents, and corporate interests. In these disputes, what some see as economic progress, others endure as generations of protests, legal battles, and unresolved suffering. Some residents even see self-demolition as the only way to end the years-long strife.

The conflicts can be traced back to various unjust colonial land practices throughout Taiwan’s history. One prominent example is the way the Japanese government appropriated natural resources through classification. In its effort to exploit Taiwan’s natural x, the Japanese government implemented a series of “pacification” policies, categorizing Indigenous people into three groups: “Raw Savages” (生番, unassimilated), “Transformed Savages” (熟番, partially assimilated), and “Civilized Savages” (化番, fully assimilated). For the “Raw” and “Transformed Savages,” who were considered less “civilized,” land ownership was acknowledged only to varying degrees or, in some cases, deemed entirely void.

A striking example occurred in 1907 when Yasui Katsuji (安井勝次), a Japanese colonial officer, initiated an essay competition designed to support the colonial agenda. The competition called for essays that argued the “Raw Savages” can not be the rightful owners of their land. Based on these submissions, Yasui claimed in his research that Taiwan’s Indigenous people lacked personhood. According to him, they were not bound by the rights, protections, privileges, responsibilities, or legal liabilities afforded under Japanese national law, rendering them non-legal persons who could be classified as animals. Consequently, their rights were systematically stripped away.

Forking the Lost Commons

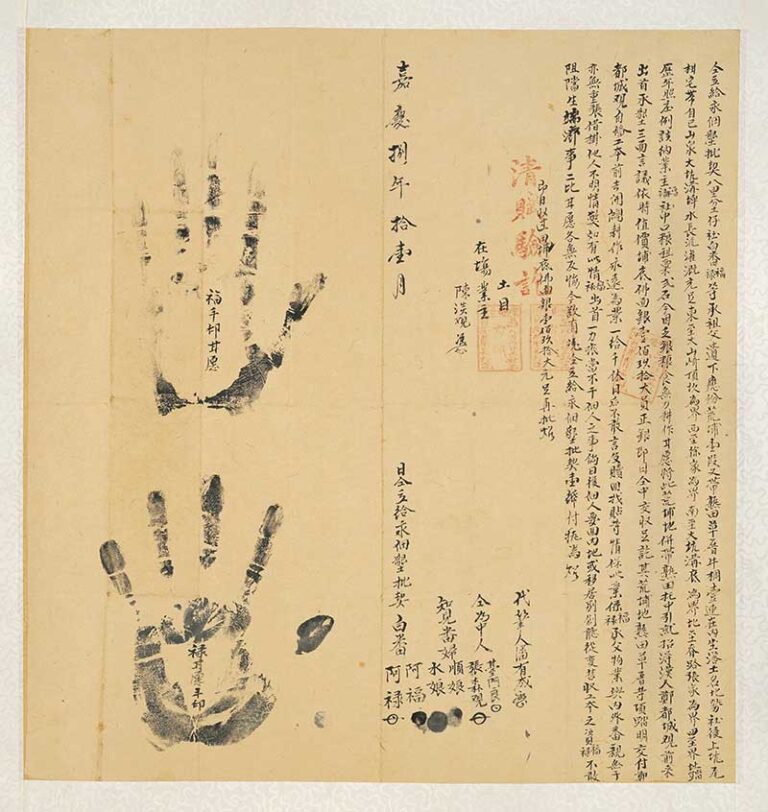

Before Japan came to Taiwan, Indigenous people had long traded their land with other communities on the island. However, the colonial manipulation had many contracts with the Indigenous people voided, thus land could be seen as ownerless, and the government made new laws stating that the lands belonged to the nation. The notion of “Indigenous people” questions the legitimacy of modern nations sovereignty, of the alleged rights to land and properties. It reveals how colonial powers have used physical and contractual violence to steal the lands of Indigenous peoples.

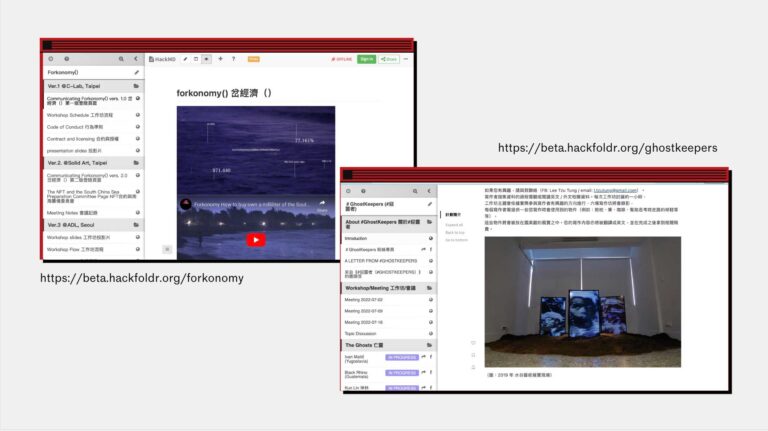

In response to this history of appropriation, Hong Kong artist Winnie Soon and I decided to make a participatory art project titled Forkonomy() in 2020, queering our idea about the commons. We organized workshops to discuss “How to buy/own one milliliter of the South China Sea (Mandarin: 南海, Nan Hai)?” and gathered diverse participants—including policymakers, scholars, marine life conservators, cultural workers, artists, and Indigenous activists—to critique the ownership of that one milliliter of Nan Hai through discussions, auctions, contract drafting, and code certificate performances.

During the workshops, we explored various forms of ownership and eventually drafted a contract together based on the ownership model selected. For example, some participants viewed the South China Sea water as “private-owned.” Since the artist of the project was the one who went near the South China Sea and collected the water to bring to the exhibition site, the participants decided the artist should be the owner of that water, and the price the water was sold for equaled the price of the artwork or the price of the artist’s labor. On another day of the workshop with a different group of participants, they chose a “co-op” model, meaning that the seawater is owned by the community, and any transfer of ownership would have to be a joint decision.

South China Sea Ownership Options:

- the seawater is owned by the community (TBD).

- the transition of ownership would have to be a joint decision.

- the seawater is owned by the bidder/artist

- the seawater is owned by the nations (current countries claiming to have the ownership of the area: China, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam)

- the winner of the bidder has to apply their ownership to these/the nation/s

- The sea is not owned by anyone that is at the current site, the bidder is pirating the seawater

- Does Taiwan need to obey the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

- To be decided by the participants

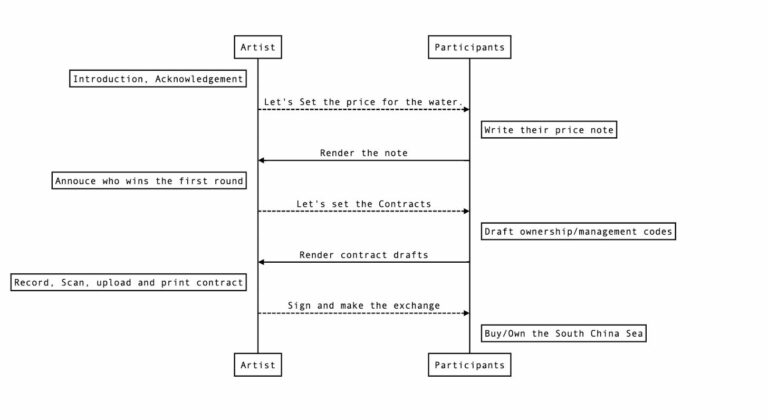

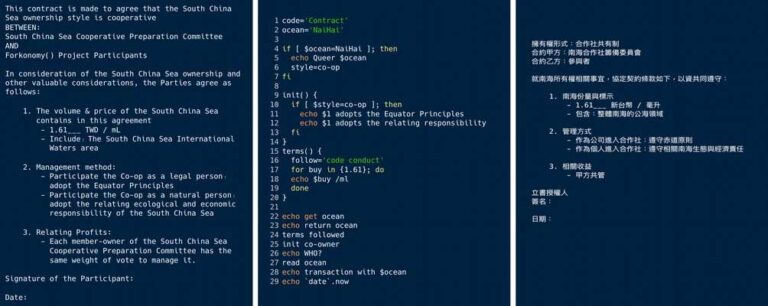

The Forkonomy() contract workshop workflow. Image credit: Tzu Tung Lee, Winnie Soon In our first exhibition, the initial participants of the action agreed that the ownership style of Nan Hai is “co-op,” with the set price of 1.61 TWD /ml (1.61 NTD = 0.05737705 USD = 0.02473149 TEZOS on 19 Dec 2020), in which each participant will take on the relating ecological and economic responsibility of the South China Sea collectively and cooperatively by signing a contract. The second version puts the agreed and the co-owned one millilitre of the Nan Hai as an NFT (non-fungible token) on the Tezo chain, and the address which purchases it purchases the contract. Further, we published 10,000 editions of the cooperative contract (written in English, Chinese, and Computer Code), and its potential royalties will be used to generate the subsequent 10,000 editions. It means that we are generating more water buyers as the co-owners of Nan Hai, and every transaction is recorded beyond sovereignties.

In subsequent workshops held beyond Taiwan, the project addressed questions of international alliances and ecological stewardship, recognizing that concerns over shared resources like the South China Sea should extend beyond regional and national boundaries. Winnie and I wanted to rethink the politics of our contemporary economy with our techno-cultural systems.

By employing free and open-source software and decentralized protocols, we positioned the participatory project as a “commoning ship” for people who want to reclaim the once-lost commons and queer current sovereignty claims, which are still constantly upheld by military threats throughout global lands, seas and cultures.

Contaminating the Self-Ownership

Forkonomy() establishes a model and practice of reappropriating, queering, and pirating economy and autonomy from a sea of commonwealth. Elinor Ostrom, along with scholars from the field of Resource Economics, often defines the commons as common pool resources (CPR). According to this definition, commons are goods that exhibit a high degree of subtractability of use and a high difficulty in excluding potential beneficiaries. Historian Peter Linebaugh has emphasized on the concept of commoning, depicting that commoning was originated from the concept of gift economy, and helps provide a bulwark of protection against rapacious state power and the wealthy, and it is a processual approach that takes into consideration the influence that we humans have upon the more-than-human.

John Locke wrote in his Two Treatises on Government (1689) that “every man has a Property in his own Person,” and “only God fully owns our lives.” However, as depicted earlier, colonial practices negated racialized bodies as “human,” canceled their self-ownership, and violently colonized their bodies.

From Marx’s perspective, capitalism compels those without means of production to sell their labor-power under the illusion of free will. Under capitalist conditions, bodies become the only means of production available to workers—bodies that are “owned” by individuals as sovereign property. This concept underpins the neoliberal notion of self-ownership, where bodies are treated as commodities, and even sexuality becomes a form of property that can be marketed or owned. This possessive logic aligns the sexualized body-object with the illusion of transparency and self-determination, creating identities that appear liberated but remain deeply embedded in neoliberal ideals and exclusions.

The term “queer,” which once represented radical difference and resistance, has increasingly been reappropriated by the neoliberal free market, producing new forms of exclusion through post-colonial spectatorship and the maintenance of identity legitimacy and visibility, thereby obscuring individual differences. The marginalized are often compelled to self-produce and adapt their identities to external norms in order to be legible within societal structures.

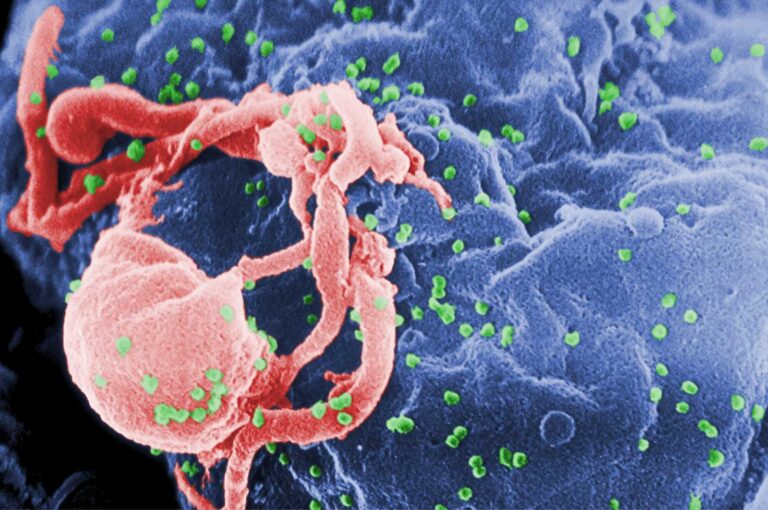

How can we perceive identity beyond the lens of self-owned commodities and toward the concept of the commons? Perhaps we need to shift from using a light microscope to an electron microscope to better see how humanity is interconnected. While Forkonomy() uses the fluidity of the South China Sea to question claims of sovereignty, my other work from 2019, Positive Coin, utilizes HIV, the AIDS virus, as a device to mock, contaminate, and apply commoning to neoliberal identities. As the virus spreads and infects among bodies, it penetrates the separation of skin-deep identity narratives. When disease is spread or “gifted” like a commons, it challenges the commodification and ownership of bodies and identities.

The Price of Stigma

Positive Coin is a digital currency crafted to play with the perceptions surrounding AIDS identity. By referencing the term “positive,” it indicates both an HIV diagnosis and how the HIV community is compelled to remain upbeat in a heteronormative, ableist society.

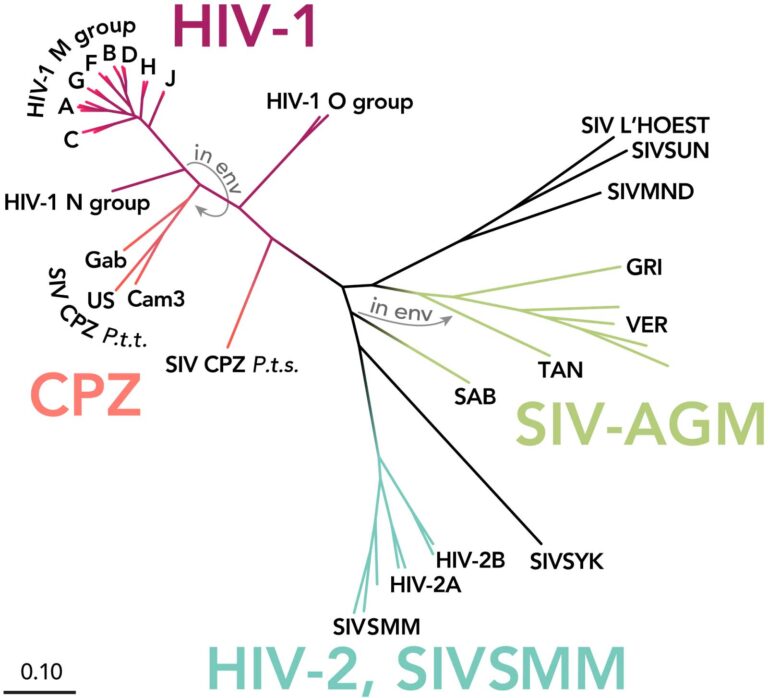

When first exhibited at Taipei C-Lab and MOCA in 2019, the coin featured designs inspired by HIV’s biological characteristics, symbolizing different aspects of the virus. Participants could purchase Positive Coins online using traditional fiat currency. Upon purchase, they received one of four types of coins, each representing one of the four major HIV subtypes. These coins were randomly distributed to participants’ digital wallets.

Mimicking HIV subtypes characteristics, the coin’s features included varying interest rates and survival times. For example, the Type 1 Coin offered the highest interest rate and the longest survival time, mirroring HIV-1 Group M, which multiplies rapidly but is less fatal and requires less maintenance compared to other strains. Different coin types had varying handling fees and maintenance costs, reflecting the differing virulence and treatment complexities of HIV subtypes. The coins expired within 14 to 21 days unless participants revisited exchange centers located in C-Lab to clear a handling fee, simulating the ongoing management and attention required when living with HIV.

Moreover, it was also designed with interactive features that simulate viral mutation. When two participants scanned their wallets at an ATM located in MOCA, their Positive Coins interacted, randomly mixing interest rates and handling fees. The ATM screen showcased a story of how HIV may be transmitted in different cultures. This feature mimicked how HIV can mutate and combine into new strains, emphasizing the unpredictability of shared viral branches under various socio-political complexities.

The project also incorporated a price fluctuation mechanism based on current stigma levels associated with HIV/AIDS. The coin’s price fluctuated accordingly: if stigma levels rose, the price of the Positive Coin increased, reducing the incentive for outsiders to purchase goods with it and symbolizing social exclusion. Conversely, when stigma levels decreased, the coin’s price lowered, making it easier for those outside the community to engage, representing social acceptance. Higher stigma levels encouraged stronger bonds and cohesion among Positive Coin holders, reflecting marginalized communities’ internal support networks.

At the project’s conclusion, participants could use their accumulated Positive Coins to bid on HIV-related artworks and goods in an art auction. Proceeds from the auction were donated to non-governmental organizations focused on HIV, creating a full monetary circle. Positive Coin simulates HIV’s growth, medical control, mutation, and the dynamics within the disease identity community, as letting Positive Coin holders experience a piece of an HIV-positive person’s life.

Homo Carceralis in Pandemic Time

Positive Coin was invited to be exhibited in Beijing from November 2022 to March 2023, a period when the pandemic was at its peak and coincided with the PRC’s 13th National People’s Congress. Due to the restrictive political climate and increased censorship, the project could hardly connect with HIV-related NGOs and artists to create a monetary circle. As a result, the project focused on gathering audience responses through a questionnaire on their perceptions of HIV control. Though the questions centered around AIDS, they also provided insight into public sentiment regarding China’s COVID-19 policies. To circumvent the Chinese government’s censorship of digital information, these audience responses were later minted as NFTs, ensuring their answers would be preserved and resistant to censorship.

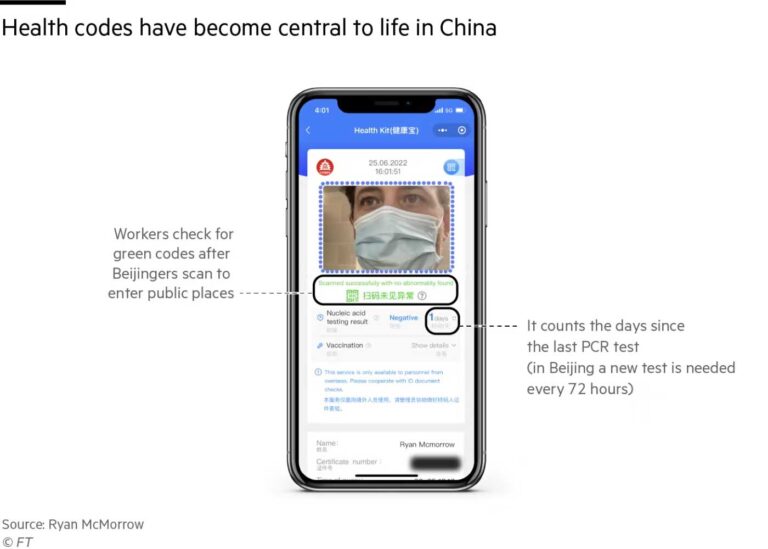

Nick Bostrom’s “Vulnerable World Hypothesis” calls for creating a “high-tech panopticon” consisting of global governance and continuous real-time surveillance of every living person on the planet. China’s stringent “Zero Covid” policy reveals the hyper-realization of such a high-tech panopticon. Numerous tragedies resulting from strict lockdown measures. COVID-control workers have locked citizens’ doors to prevent them from going outside. Students who began college in 2020 were confined to campus for almost two years. The “green” health code app is required everywhere in China; it identifies an individual’s COVID-19 risk level as red, yellow, or green. There have been reports of authorities using the health code to restrict public gatherings or access to public services. In June 2022, over 1,300 depositors of bankrupt rural banks in Henan found their health codes turned red, preventing them from attending a protest in Zhengzhou. One protestor responded, “They are putting digital handcuffs on us. Many citizens are either accused of criminally interfering with pandemic prevention or of inciting subversion and provoking trouble. According to scholar Jackie Wang, it is a “carceral laboratory”—a zone where new control techniques are tested on society’s “others.” Every living, breathing person becomes a potential risk for “civilizational vulnerability” and a subject of suspicion. Social, health, and ethnic minorities have become objects of intense surveillance. China’s prisons, police, and hospitals are used to displace and control COVID-positive people, Uyghurs, and protesters.

The situation is similar to the AIDS pandemic: in the name of public health measures, individual freedoms were restricted, surveillance increased, and stigma against certain identities was heightened, creating long-term socio-economic and mental health crises. Exhibiting this work under China’s most fervent pandemic control reenacts the hyper-realization of such a high-tech panopticon.

Though the project is called Positive Coin, NFTs and blockchain technology were used beyond mere financial design; they serve to semi-permanently preserve the audience’s information to avoid authoritarian interference. It signifies the control that led citizens to silence, and each coin now encapsulates the emotions fueled by state paranoia.

The Viral Gift Economy

As in China’s politics, control and surveillance mechanisms have infiltrated the individual body. Hospitals, schools, and policing systems—these architectures of disciplinary power—are electrified, miniaturized, and embedded in digital personal communication devices. The public health system extends the national surveillance plan. To maintain a “healthy,” “clean,” “productive,” and “reproductive” state, biotechnological records and digital pharmaceutical transcriptions are used to enforce counteractions that diminish or ostracize deviants.

If the Positive Coin symbolizes the AIDS virus, the entire project is designed to let participants hold and chase AIDS. Despite many punitive notions of AIDS, some people also see HIV as a gift. “Bug chasers” are those who intentionally seek HIV infection, and some HIV-positive individuals purposely seek out others to infect — known as “gift-givers.”

There are many reasons for chasing the bug; one is viewing it as a sexually and personally empowering act. While health policies promote safe sex and send threatening messages about how horrible AIDS is, many bug-chasers wish to overcome the sense of isolation resulting from “cold, sterile” protected sex and the fear that has long hindered their search for intimacy. Additionally, an HIV-positive status provides a shared identity and sense of community. It serves as a political device and action against social norms and heteronormativity, which include rigid conformity to safe and healthy sex practices. Though many treatments are available today, bug chasing can still be regarded as an active suicidal behavior that confronts one’s fear of death with the fear of isolation.

Bug chasers exemplify the complex outcomes of health control and societal stigma. In AIDS and Its Metaphors, Susan Sontag describes how militaristic language frames disease narratives, depicting AIDS as an internal enemy and a punishment for sexual deviance. This dual narrative of punishment and internal disorder contributes to a sense of shame that is not easily addressed by society’s “positive” discourse, while also reinforcing governmental control by justifying surveillance and intervention in the name of public health.

When surveillance, shame, and vulnerability are imposed by state paranoia, the neoliberal concepts of identity and self-ownership become illusions. Suddenly, the body is downgraded to a biological carrier of disease, prompting the state to exert its power to prevent its spread to the “human”. Military narratives never aid in healing, yet the pandemic virus has then been transformed into a shared enemy within an illusory narrative. Its commoning features infiltrate individual boundaries and disrupt well-maintained identity governance.

Bug chasers can be seen as an outcome and an outcast of bodily panopticism; however, this can also be viewed inversely, where individuals actively embrace the virus to disrupt the government’s attempts to control their bodies through fear, shame, and surveillance. They are creating a common economy—an inverted system of gift economy where gifters create interconnected experiences that infiltrate individual boundaries and traverse the dichotomies between human and non-human, pride and stigma, able-bodied and Crip.

Collaborative Fluid Sculpture for the Static Political Dilemma

Both Forkonomy() and Positive Coin exemplify how artistic and creative uses of technology can challenge entrenched economic illusions. The ease with which seawater transitions between gas, liquid, and solid states emphasizes fluidity, and travels between nations demonstrates how unquenchable, rigid ownership and capitalism desire chase after every form. Similarly, at the viral scale, market identities make no separation. The colonial government and its spectatorship try to extend their boundary claims at the viral scale, yet none-of the physical bodies can exercise its control as the sole owner of its microbes and unique diseases; our bodies and cells have already collaborated with non-humans as shared commons. In the blockchain realm, which is slightly beyond government’s reach, humans and nonhumans—including animals—can have an address to keep their voices and records intact when contracting and transacting.

In addition to the above projects, most of my artwork is openly licensed under Creative Commons (CC-BY-4.0); all audiences and creators are free to use the design materials, duplicate the artwork, or continue the work with their own variations, just as with any kind of open-source software. As my ideas come from all parts of the world and are a connection with others, I use this method to challenge the idea of ownership between the artist and their artwork.

As a Taiwanese queer artist, I believe it is important to experiment with the current economic situation. Facing a neighboring totalitarian regime, the islanders naturally developed a nationalistic narrative for independence, while overly reliant on the high-tech TSMC and AI economic systems to support our democratic society. It becomes crucial to use creative methods to queer static nationalistic and economic imaginations. By doing so, artists create gaps between the layers of national pride and economic growth, sculpting multiple universes that can transcend daily political pressures and dilemmas.

Bibliotheque

Share

Author

Lee Tzu-Tung is a Taiwanese conceptual artist and curator. Growing up amid Taiwan’s multifaceted generational identity struggles, they questions: “How marginalized communities ‘queer-up’ contemporary hegemonies after generational traumas?” and employs open-source principles, decentralized tools, and participatory practices, inviting audiences to become co-creators and reflect within their art projects. Lee has also been actively involved in Taiwan’s political scene. In addition to working in two Taiwan parties, they organized monthly conferences for Café Philo Chicago (2016–2018), participated in the NGO Overseas Taiwanese for Democracy (2016–), and served as an editor for the bilingual political magazine New Bloom (2016). Lee also led and designed visual elements for a 200-person rally against Black Box Education (2016), coordinated a nationwide rally across 40 cities advocating for Marriage Equality (2017), and organized the Indigenous protest Passage of Time (2017).

Lee holds an MS from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Their work has been exhibited internationally, including at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, MOCA Taipei (TW), MIT Museum (US), Lisbon University (PT), ArtScape (CA), Transmediale (DE), Philosopher’s Stone Gallery (KR), Hyundai Studio (CN), and Asymmetry Foundation (UK), among others.